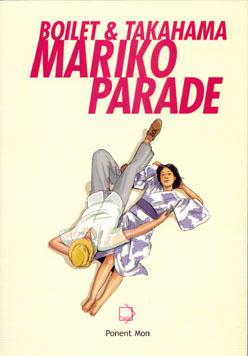

| Mariko

Parade

The

hardest reviews to write are not the ones about comics that

are so horrible that it is simply work just to get through

the reading of them. Those reviews provide me with a spectacular

chance at cathartic bashing and sarcastic joke making. And

I love the little buggers for providing the opportunity

to complain.

The

really hard reviews are the ones about comics that I think

are almost beyond my abilities to critique. I’ve never

been comfortable reviewing stuff from Moore or Ellis or

Eisner, etc. I do these reviews because I want people to

read the books, but I know that there are things that I

am just plain not worthy of, so I try to mention everything

I like about the book, and always forget to mention at least

a hundred storytelling devices or plot points that I meant

to include, in hopes of painting a true picture of what

makes said comic great. I almost hate these reviews because

it is rare that I think I’ve ever done a really good

comic justice with my review. I always forget something.

I’m

at that point once again, where I am faced with a book that

is intelligent, beautiful, and unique in the way it is presented,

which just happens to be the sequel to a book I’m

sure I didn’t give enough praise to: that graphic

novel being Yukiko’s

Spinach.

In Yukiko’s

Spinach, French mangaka (manga artist) Frederic Boilet

told the semi-autobiographical story of his love for a Japanese

woman named Yukiko and their subsequent falling out of love,

though perhaps not in the case of Boilet. His unique combination

of photography, computer graphics, and regular pencil work

helped concoct one of the most affecting graphic novels

I’ve ever read, and Mariko Parade follows

suit.

In Mariko

Parade, four years have passed since the publication

of Yukiko, and Boilet and Mariko, the model who

posed for the artwork in Boilet’s first “manga

nouvelle” collection, go on a small vacation to the

island of Enoshima to shoot some more pictures of Mariko

and enjoy some time to themselves. In the four years since,

Mariko has been Boilet’s only model and only love

and the story that follows them on the island of Enoshima

is nothing out of the ordinary.

The

biggest change from Yukiko is that Boilet has brought

on Kan Takahama, a Japanese manga artist, to illustrate

the time spent on Enoshima while Boilet weaves several short

stories comprised of his own artistic techniques into the

Takahama’s Enoshima narrative. The result is spectacular

fusion of two artists and their styles that help create

an amazing tale of…well, melancholy would be the best

word for it.

I’m

reminded of Lost In Translation every time I pick

up something from Boilet. It wasn’t a movie I particularly

liked, but I did understand it and I think it got the point

across that there are some very distinct differences between

the American and Japanese cultures. While Bill Murray and

Scarlett Johannson focused more on the pop-cultural and

social differences, Boilet manages to point out some of

the more delicate differences as it refers to the Japanese

and love.

“Don’t

ask me why but the Japanese…are inclined toward that

which is fleeting or sad. They say it’s in their nature.”

The contrast that Mariko and Frederic represent is a glaring

one: Boilet being French is so very indicative of the happiness

that arises during love, while Mariko seems so very much

a part of the sadness involved in relationships, and the

knowledge that relationships can sometimes end. The way

they play off one another is subtle and a narrative battle

between these two aspects of love is fought beneath the

surface of this small story about a vacation in Japan, and

neither side really wins.

|

Again,

I’m staggered by the poise of the stories from Boilet,

and indeed from Ms. Takahama, as her artistic renderings

greatly compliment Boilet’s slow storytelling style.

There’s not a line of wasted dialogue, which is odd

because there are times in the script when Frederic and

Mariko talk about nothing overly important, perhaps Boilet’s

very European obsession with soccer. But even these times

when the dialogue seems meaningless, the subtext provides

meaning. References to “torn muscles” and distraught

players easily keep our attention on the overall tone of

distress that permeates the book.

Takahama’s

artwork is everything I want manga to be and more. Instead

of speed lines and bug-eyed fourteen year-old girls, the

art put forth by Takahama is full of texture and depth.

Unlike many mangaka, she puts backgrounds into her work,

but these aren’t the super detailed backgrounds of

books like Akira, but impressionistic backgrounds

where the reader can easily make out the pencil strokes

that Takahama used, and maybe the weight of lead she used,

providing the texture discussed earlier. And she shades

her work! There’s no inking on her artwork; she gives

the straight pencil work as her finished product, and then

Boilet seemingly helps to add in grey tones and deepens

the shadows in part. What really impresses is the easy flow

to and from Takahama’s illustration and Boilet’s

photography. While each style is obviously different, they

compliment each other extremely well.

I have

forgotten to mention many things, among them the honesty

of this graphic novel. The story is so simple. It’s

just a slice of life from a vacation with and artist and

his model, who speak in certain terms and talk the way people

in love might talk. There is something so incredibly genuine

about the work that comes out of this manga nouvelle movement.

It’s so honest in its execution that I am never able

to really describe my reaction accurately. The truth about

love, about the character’s relationship feels very

real and that type of realism is hard to come by in comics.

Usually that “realism” in comics simply means

something dark or edgy or pessimistic, but Mariko

is both sweet and sour. The love of the characters comes

through just as easily as the subtext of pain in the book.

This kind of storytelling reminds me more of Harvey Pekar

than anything else. It’s just honest.

I’ve

droned on enough for now, forgetting to mention everything

I wanted to, but I think I’ve given enough in way

of praise to maybe make you drop the cash on this deserving

book from Fanfare/Ponent Mon. Only $17.99 will get you this

gem of sequential art, which is nothing to pay for something

that is this beautiful. Hard review, but a great comic.

Mariko Parade

|