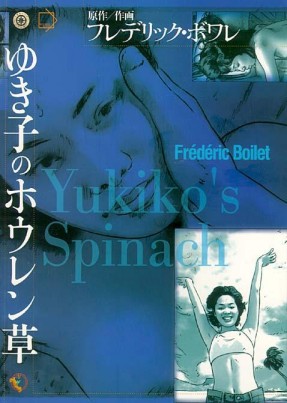

| Yukiko's

Spinach

Something

about comics separates them from all other genres of literature.

It’s something hard to define and hard to put into words,

especially for the comic book reader of many years. Most of

us comic aficionados have been reading comics for so long

that we understand them instinctually: we never have to worry

about understanding visual narrative or following text and

art panels across a page, or several pages, because our minds

are so in synch with sequential art and the rigmarole involved

with it that we can understand almost anything in comic book

form (except Chuck Austen’s writing). It is rare that

we find ourselves unable to grasp a piece of comic literature

in scope, plot, structure, or any of a thousand attributes.

For this reason,

I’ve found that I infrequently reread my comics. Save

for most of Alan Moore’s and Warren Ellis’ works,

and the indomitable Gaiman, few books catch my eye more

than once or twice, because I’ve gotten so used to

comics as a medium that I absorb them in one sitting. Complexity

is the only thing that will call for a reread these days.

I’ve

read and reread Yukiko’s Spinach probably

a dozen times in the last three weeks.

It is

the intimate and biographical portrait of Frederic Boilet’s

love affair with Yukiko Hashimoto. Boilet is a French artist

and a “mangaka” (Japanese for comic artist)

with a unique photographical artistic bent for creating

comics: he photographs his subjects and landscapes, then

uses filters to makes them appear as line drawing, while

at the same time including traditional line drawing in his

work.

Told

from Frederic’s perspective, much of the time from

the first person viewpoint, Spinach is the story

of Boilet’s meeting of Yukiko, a Japanese girl with

which he is immediately fascinated and the brief romance

they shared. It is a collection of small intimate moments

between the two, structured to reveal Frederic’s deep

feelings for the girl, as well as their mutual understanding

that their relationship is finite.

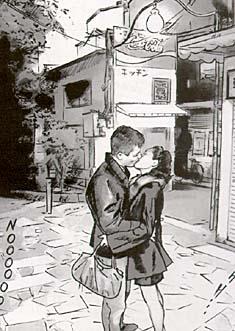

This

is the most intimate written work I’ve ever read and

I use the word “intimate” because I cannot think

of another word to describe the connection to the reader

that Boilet establishes. The first-person perspective as

a storytelling device is one rarely used in comics, at least

the literal first-person view. As a result of his photographic

style, much of the story unfolds from Boilet’s eyes;

we see what he sees. We are there as he falls in love with

Yukiko, and it’s her hauntingly beautiful face we

fall in love with. We see them make love, and we are participants

in the act. The body language that his camera and pencil

capture convey so much more emotion and depth than the standard

of comic art, letting words fall away and letting the images

speak for themselves for large parts of the book. And while

there are times when “silent” comics are simply

easy ways for the writer to avoid having to write, it is

not the case in Yukiko’s Spinach because

each panel of art is rife with meaning, emotion, and intention.

Also

of importance is that I love the depictions of sex in the

book (surprised fanpeople? I thought not), and not for the

standard pornographic reasons. Sex in comics too often takes

on the violent and male-oriented attributes of its clichéd

audience. If it ever happens in mainstream comics, it’s

usually some morality tale about the evils of sex, or it’s

basic fantasy fulfillment (Conan comes to mind), or it’s

just plain weird (anything by James Kolchaka). Much of this

applies in the Indie comics scene, though not all of it.

Other than “Sex, Stars, and Serpents” from Moore’s

Promethea, I can’t think of a time when sex

has been presented so evenly. It’s presented as a

beautiful act between Boilet and Yukiko, and it’s

arousing in both the physical and intellectual way. It’s

not angry. It’s not cynical. It just is. The photorealistic

touches, coupled with the subjects’ kinesthetic qualities

make the act an experience for the reader. It’s a

participatory text and the reader gets to participate in

an honest, realistic, and true sex act and it’s something

I’ve never seen in comics before.

|

The book has

an underlying tone of sadness, as many love stories are

possessed of both the good and bad, but Boilet never lets

melancholy overpower the joy of the relationship, despite

both he and Yukiko knowing that it will not last forever.

Even when Boilet plays with the sense of time, shifting

scenes back and forth to the beginning of the relationship

and the end, sometimes placing dreamy imagery intermittent

with the more linear panels, we never lose the sense of

emotion that pervades the work. This is love; the good,

the bad, and the ugly of it and Boilet has no problem conveying

the raw sensation of it, nor the passion inherent in it.

Boilet is not afraid to feel and the reader feels right

along with him.

The

artwork makes Yukiko’s Spinach the absolutely

genius work that it is, and Boilet’s use of computer

graphics is subtle and unobtrusive, actually enhancing his

story in a way that may not have worked if he left it as

simply photographs, or just as line drawing. In combining

the two almost seamlessly, he creates a photorealism that

is, to a small degree, attempting not to be realistic. It’s

so gorgeous and fresh that I have to wonder why it hasn’t

happened more often in American comics (the French and Japanese

are well exposed to Boilet as both manga and bande dessinee),

as the only example I can dredge up is Steven John Phillips

from works like I, Paparazzi and Veils.

This

is a spectacular work of sequential art literature and should

be on your graphic novel shelf. The $13.99 that Ego Comme

X (the French publisher) or Fanfare/Ponent Mon (the English

publisher) is charging is well worth it considering the

level of creativity this comic is on. I recommend you order

through your local dealer or a bookstore because this is

one of those hard to find books. Go off and enjoy this rare

and reread-worthy story, and damn Boilet for making the

French seem likeable again.

|