| A

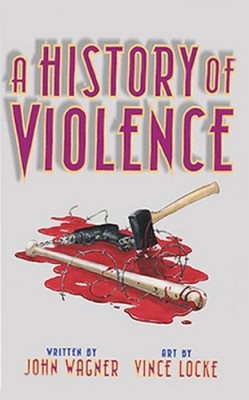

History of Violence

I see problems

on the horizon for the comic book industry. These are not

problems that will be insurmountable, nor will they be problems

caused solely by the industry, something that seems to happen

a lot in these familiar realms that deal with overzealous

fanbases and editorial oversight. But they will be problems

that will have a tremendous effect on how comics are ultimately

viewed by the public. Our problem is shame and how we deal

with it.

Sitting

on my desk is a copy of John Wagner’s and Vince Locke’s

A History of Violence. Some people who have just

read that line have thought: how did he get a copy of that

Viggo Mortensen

flick so soon? Many of you reading this might have already

known that the said Viggo flick was indeed based upon a

comic book property from Paradox Press, but I’m willing

to bet that a fair number of you didn’t have a clue.

I didn’t when I first saw this sitting in the graphic

novel section of a Borders bookstore.

As I

looked at the cover and saw the words “Soon to be

a major motion picture!” printed at the top in plain

black ink, I tried to think how this could have slipped

by me. I am in no way saying that I’m any type of

authority on comic books, that I should be some hub of funny

paper information, but this is rather huge. The movie of

the same name as the graphic novel has garnered massive

critical acclaim, and some have been talking about Academy

Award nominations for Viggo and his costar Maria Bello.

Every Access Extra Hollywood Hot Minute celeb news magazine

has had an interview with the director or the cast, and

every one has talked about the powerful story behind the

film. Not once did I hear the words “graphic”

or “novel.”

I have to wonder

where this is coming from, because the comic itself is the

stuff of Eisner Awards. Suspense is hard to convey in comics,

because we can turn the page and know what is coming next

without always reading the dialogue and text, since the

visual language usually speaks somewhat louder than the

written. A comic book writer cannot control the way his

or her comic is read the way that a film director can control

the speed of his film; the speed, the presentation of the

comic book material is more controlled by the reader than

the artists, whereas the cinema viewer can only take in

the material as quickly as it is presented by the filmmaker.

So it is damn hard to really make a comic suspenseful, to

keep a reader guessing, and that is what Wagner and Locke

have done. They have made a true suspense thriller in comic

book form.

Tom McKenna was

just closing up shop one night when two malcontents thought

robbing the small town diner was more fun than murdering

hitchhikers. When it comes down to violent action, Tom manages

to kill or cripple both men, saving his own life and becoming

the small town hero he never wanted to be. He just wants

all the media attention to go away and get back to living

his happy familial life, when some dangerous men start asking

questions about Tom and his supposed “life.”

Believing him to be someone else, these strangers begin

to add a certain level of disquiet to the small town of

Raven’s Bend. Tom is pushed to the limit of danger,

and we get to watch as he and his family try and deal with

a threat that the ordinary man is never meant to deal with.

The level of

writing and artistry on this book is superb. Wagner creates

his characters well, but doesn’t give the reader any

real character knowledge until after the first third of

the book. He lets the reader walk into the story blind,

faced with the characters as they live their lives and knowing

about the characters only what is immediately apparent through

their daily interactions with each other. Not knowing the

characters thoughts or motivations make the story nail biting,

because while Wagner gives us fully developed characters,

he doesn’t tell us anything about them. We don’t

know how dangerous the men seeking Tom are and we’re

even less sure about how dangerous Tom is because he could

be telling the truth about being just a normal guy from

a normal town. But he could be lying. The fact that we don’t

know until the second act, where Wagner fills in the background

story, is wonderful, especially in the day and age of single-issue

story plotting and six-issue arcs. By the time we get to

know Tom, we’re dying to know Tom.

The artwork by

Locke is not artwork I would usually call wonderful, but

it so meets the needs of the story that I can’t help

but applaud it. Locke appears to do all his artwork in ink

pen with a thin scratchy line and he seems adept at the

nearly lost art (in comics) of crosshatch shading. His figure

work is not polished, but instead very raw in form and he

uses that to great advantage when relating the suspense

of Wagner’s script. Since his artwork more closely

resembles ink sketching, it looks unfinished at times, almost

uncertain, lending nicely to the uncertain elements of the

story. His artwork defines the uneasiness of every scene:

every time Tom and his wife are afraid for their family,

every time a gun is pointed in someone’s face. His

shading techniques end up making some great dark shadows,

also indicative of the crime/thriller genre, and even though

his sketched style is far from stable, he manages to convey

emotion, action, and absolute horror whenever the script

calls for it.

With the artistry

of this book from in question, I still wonder why I haven’t

heard anything about this movie being a comic book first.

I think we’ve entered a time when the comic book has

at least been able to grab significant attention through

its recent onslaught on the movie industry, if not always

gaining critical approval. But I can see the distinct difference

between a “comic book movie” and a movie; there

has to be some idiot in leather chaps or a cape before people

will start talking about comics. If we have a movie like

Daredevil or Spider-man, we’ll hear two things from

at least one member of the cast or the director “I

was always a big fan of the <fill in name here> comics

when I was a kid,” or “I wanted to bring back

that feeling of reading a comic book when you were a child

with this scene.” Then, inevitably, Stan Lee will

come by and explain how he got the idea for the comic, and

about how cool it was. All talk of comics in the mainstream

media is tied up in two things: superheroes and children.

Comics are, essentially, viewed as something for kids, even

after all these years where it has been decades since the

actual market depended on kids as the main audience.

But

this isn’t all the media’s fault, tough they

share plenty of the blame. Part of it is the comic reading

community. I believe we’re still stuck in the mindset

that somehow, unless the attention is focused on a large

property or a major character, we should keep hush about

comics. I call it fanbase syndrome: we’re willing

to dress up in lycra and tights and go to premieres of our

favorite superhero movie, but when a comic book movie comes

along that turns out to be just a good story that used to

be in panels we ignore it and treat as just a movie. I remember

when Road

to Perdition came out, and everyone applauded the

performances of Hanks and Newman, and no one talked about

Max Allan Collins' original graphic novel on which the movie

was based. And I’m talking about comic readers, not

just the media. Where was the fervor around Hank’s

performance and the constant comparisons between his portrayal

of the character and Collins’? Did we do a lot of

contrast and compare on Daniel Clowes' Ghostworld?

When

I think of the sheer idiocy of campaigns like the “Bring

Back Hal Jordan,” I am also forced to face the fact

that, if given incentive, we’re willing to make big

fusses over comics. Why aren’t we willing to do that

over the smaller properties like A History of Violence?

Why aren’t we out there raising a ruckus so that more

people than just the comic book reading community know about

great comics becoming great movies? Why aren’t we

handing out copies on street corners?

I know

some people have said that they feel as if they’re

pushing comics onto people when they recommend them for

reading. And I say, “Good.” Because you are

pushing them, and you should be. They’re a unique

art form, and one just as capable of being intricate and

meaningful as written word literature. There’s no

reason to not give someone a comic if you know they’ll

enjoy a good story, graphically represented or not. At times,

it seems as if we’re ashamed of word balloons and

panels and splash pages, which is a shame, considering we’re

the only people who can convince others of what we’ve

always known; comics are a medium of expression as important

as any other.

I’m

certain this has all been said before, probably by someone

far more eloquent and better equipped to speak on the subject,

but I had to put it down on paper after reading this comic.

I found it sitting on a clear plastic rack, next to empty

spaces and a few copies of Chobits. It wasn’t displayed.

There was only one copy. I can’t help but feel as

if it and its creators deserved better than that.

A History of Violence

|