|

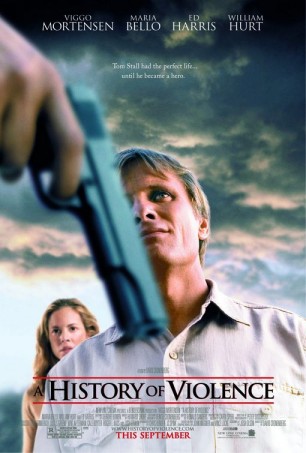

A

History of Violence

The title of David Cronenberg’s latest film feels

ironic considering the director’s filmography, although

it is doubtful that it is intended to be.

His

latest effort, based on the graphic novel of the same name

written by John Wagner with art by Vince Locke, is not merely

an adaptation, but more a contemplative dissertation on

violence as it resides in our genetic heritage, our pasts,

and most importantly our individual futures.

The

plot is simple enough, centering on a mild-mannered family

man named Tom Stall (Viggo Mortensen). Tom owns a diner

in town called Stall’s Diner, and lives a relatively

quiet life with his wife Edie (Maria Bello) and their two

children Jack (Ashton Holmes) and Sarah (Heidi Hayes). Altogether,

life is good for the Stalls, they are well known by the

townsfolk and live day to day in relative home-spun bliss.

Jack

is the only Stall who seems to suffer initially, and most

of his struggles equate to High School awkwardness and growing

pains. At breakfast Jack explains to his father that he

dislikes P.E. class, specifically softball, to which Tom

tries his best to comfort and console his son. In a moment

of triumph, Jack manages to field a game-winning catch,

which happened to belong to a bully in his gym class which

results in Jack being pushed around and called all sorts

of names in the locker room.

Despite

this egregious behavior, Jack diffuses the scenario with

humor and wit, narrowly avoiding a potentially violent situation.

In essence, Jack does what he feels is right, and manages

to come out on top temporarily.

One

night, while closing up the diner, Tom is confronted by

two very insistent ne’er do wells thirsting for coffee,

and perhaps more. Guns are pulled, lives are threatened,

and Tom springs into action, brutally slaying his attackers

and saving his life along with those of his employees in

a fell swoop. Tom’s heroics make him the talk of the

town and a media celebrity in a blink of an eye, and before

long a new set of characters begin lurking around town and

Tom specifically. Tom makes for a bashful interview, insisting

that the sooner this thing blows over the better while claiming

that anyone would have done as he did in such a situation.

When

confronted by the nefariously mangled Carl Fogarty (Ed Harris)

in the diner the next day, Tom is stunned to be persistently

referred to as Joey, a name he insists is not his. Carl

believes that Tom is a man named Joey Cusack, a mob thug

from Philadelphia, and this “Tom” persona is

merely a guise to afford Joey a chance to start over.

This

poses a problem for Tom, who insists that he is not who

Carl claims he is, yet the strain begins to show as the

family, Edie and Jack specifically, begin to question the

sudden changes in Tom’s behavior and demeanor. Whether

or not Tom is who Carl claims him to be is an interesting

predicament to ponder, but the real brilliance of this tale

stems from Cronenberg’s analysis of violence and duality

of man, two themes he has championed in his work from day

one.

Those

not interested in spoilers should likely leave this review

with that.

Cronenberg’s

adaptation is painted in shades of subtle brilliance. This

is, hands down, the director’s most accessible work

since 1986’s The Fly. Cronenberg continues

to churn out amazingly well crafted tales that dip into

the remotely bizarre and intriguingly realistic.

Mortensen’s

performance is compelling, and the look and feel of small

town life is utterly simplistic yet believable throughout.

Maria Bello shines as Tom’s concerned and devoted

wife, and she develops Edie in very subtle movements as

the events start to ratchet up to suspicious levels of tension.

Ed Harris turns in a chilling turn as the gnarled face thug

Carl, a man so seemingly supernatural that his fate comes

as a shock.

Lastly,

yet certainly of note, is William Hurt’s surprise

turn late in the third act of the film. To divulge his name

or character’s motivation would be a disservice to

the film itself, but to put it plainly, this is a side of

Hurt that has never been exposed before on camera, both

humorous and odd wrapped up in an appetite for danger.

Moving

along, Cronenberg examines violence here in interesting

subtleties. An early act session of intimacy is depicted

in long shot, almost uncomfortably natural and earnest while

invoking the feeling of near voyeurism although never stooping

to mere exploitation. This sequence is wholesome, even if

the content is raw and distinct. This sequence is paralleled

in the later acts with another session of intimacy, this

time following certain revelations regarding Tom’s

past. This time passion is not delicate and nurturing, but

instead a flurry of pushing and pulling, restrained force

with a grippingly dark edge. The contrast is too distinct

to be missed.

Another

sequence of note comes in Jack’s arc, in which a second

confrontation with his High School bully comes to an entirely

different conclusion than first witnessed prior to Tom’s

encounter in the diner. Tom clings to his ideals, despite

being able to repress his inner “Joey,” a raucous

killer capable of doing that which the meek Tom is incapable

of doing. Without Joey, Tom was doomed to perish that fateful

night, just as without the emergence of Joey, Jack would

have continued along his passive course of dealing with

conflict.

Justification

of violence? Hardly. Cronenberg never stoops to glorifying

the bloody and grotesque conflicts his characters encounter.

Instead, he seems to be raising the questions: Is a violent

nature able to be curbed? What is worse: attempting to atone

for sins passed, or never having sinned at all? Are we forever

judged by our past, or do our actions in the present make

any difference in this judgment?

A

History of Violence intends to pose, not answer, questions

such as these in regard to individuals and humanity as a

whole. The film succeeds, and leaves us with yet another

brilliant Cronenberg vehicle to mull over and reflect upon.

Rating:

|