|

One For

The Ages:

Barbara

Gordon and the (Il)Logic of Comic Book Age-Dating

A.

David Lewis, whom we profiled a few weeks ago, has been

lecturing and writing on comic book scholarship for quite

some time. As a result of our doing a story on him, he offered

this piece to Once

Upon A Dime.com. I'm publishing the introduction here,

so as to whet your appetite for the complete thing on Donald

Swan's website.

|

When undertaking

the question of the comic book Ages, one could look no further

than a character from that selfsame medium, Barbara Gordon,

as a guide. Best known as DC Comics' Batgirl, Barbara Gordon

provides a useful entry point into the discussion of comic

book classification and dating nomenclature. The heroine long

ago hung up her chiropteran tights out of necessity: a gunshot

would to the spine left the librarian-by-day/vigilante-by-night

permanently paralyzed from the waist down. Moving from the

physical to the cerebral, the paraplegic turned handicap into

opportunity and reinvented herself as Oracle, remote "freelance

information broker who specializes in metahuman activities"

and "the JLA's secret member" (Morrison, 1998: 1,

75).

In this

role, she essentially acts as one of the superteam's most

"analytical thinkers" and information sources (Morrison,

1998: 123). Credited as being "a genius-level intellect

with a near-eidetic memory and a master in her field"

(Howze, 2003) as well as Wizard magazine's Greatest

Super-Heroine of All Time, Barbara is, to one way of thinking,

both the superhero most emblematic of and the icon most flattering

to the comic book scholar.

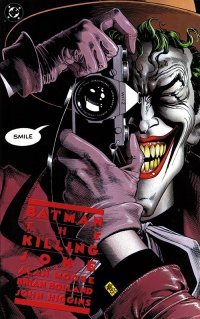

With Barbara

in mind as a muse, start with a crucial scene from her history,

that of her crippling in Alan Moore and Brian Bolland's Batman:

The Killing Joke. She is at home with her father, Gotham

City's Police Commissioner Jim Gordon, as he clips the latest

Joker article for his scrapbook. This scene follows pages

in which Batman occupies his lair, studying the little concrete

information he himself has on the Joker. In both the case

of the scrapbook and the Batcave database, classic, Golden

Age images of both Batman and the Joker appear, though the

savvy reader knows that these versions have been overwritten

by subsequent decades of creative teams and retroactive continuity

(retcon). With his sloppy pasteboard system, the Commissioner

is unbothered by this, mainly because he doesn't focus highly

on precise dating: "Look at this one. First time they

met. Now when was that?" (Moore, 1988: 12). Barbara,

on the other hand, has an altogether different approach: "Some

day you ought to let me work out a proper filing system, like

we used at the library" (Moore, 1988: 12).

In

his book How to Read Superhero Comics and Why, Geoff Klock

notes this moment, saying: In

his book How to Read Superhero Comics and Why, Geoff Klock

notes this moment, saying:

Such

a system [as suggested by Barbara], however, would be impossible

when a contemporaneous article was authored by another character

practically written out of continuity, Vicky Vale. History

flows through the whole of The Killing Joke, but particularly

in this scene of Gordon's book keeping. Most revealingly we

are given a moment that reflects on the pastiche quality of

Bolland's art […] Barbara remarks, "Urrgh. Look,

you used too much paste! It's all squidging under the edges

of the clipping," exposing the artifice of the pastiche

and emphasizing the difficulty of making the pieces fit together

nicely. And Gordon literally tries to fit Batman's history

into a whole (2002: 59-60).

Klock

further argues, though, that a character's reaction to this

discombobulated history is what helps to define them. "Batman's

response is to organize the chaos, the Joker's to embrace

it, but Commissioner Gordon simply cannot remember" (2002:

60). Barbara, similar to her mentor Batman, wants to remember

and wants to organize Bolland's pastiche. Most of all, though,

she simply wants to have a logic to the system by which history

is dated. And, in that general manner, one should follow Barbara

Gordon.

Some,

though, would argue against wrangling with the Gordian (or

Gordanic) knot of chronological comic book classifications

- The Ages. Some, akin to the Commissioner, would rather not

be bothered with scrutinizing where one age or stage of the

genre ended and the next one began.

In his

1997 article for Comic Book Marketplace, Lou Mougin highlights

the arbitrariness of such labels. First, "it can be argued

that all these 'Ages' apply to superhero comics only"

(1997: 71). But, instead of being begrudging about this limitation,

it is more useful to whole-heartedly embrace it; it is an

acceptable, even welcomed, limitation to this corpus, giving

it a manageable shape.

Still,

there is the subjectivity of determining what is and is not

a 'superhero comic'; there is also the imposed back-dating

of the Ages with which to contend. "You can really only

identify the Ages that are clearly over," says writer

Kurt Busiek (Lewis, 2002). "So, the one you're in at

the moment is always called 'The Modern Age' until you give

it an actual name - because then you've put a headstone one

it and you're on to the next one" (Lewis, 2002).

So, not

only is the content of an Age determined by outside forces,

but also its span. This constructedness leaves Mougin to ask,

"Were there really Platinum, Golden, Silver, Bronze,

and Whatever Ages?" (Mougin, 1997: 71). In the end, he

is basically resigned to the frustrating group consensus that

"now we have four 'metal' Ages (Iron/Platinum, Gold,

Silver, and Bronze)…and it's only a matter of time, an

age, really, before somebody gives us another age" (Mougin,

1997: 71), even if there is no mass agreement to those headers

and no driving rationale behind their creation. This sort

of haphazard, slipshod arrangement barely qualifies as organization

- continuing Klock's Batman analogy, Mougin sees the Ages

as more Joker-esque, operating in a world either without logic

or with a twisted one, than like the Commissioner or Barbara

or even the Dark Knight himself.

All this

subjectivity doesn't invalidate the Age-dating system; quite

the contrary, it invites any number of outside interpreters

to make sense of its content. And plenty have. So, before

adding this article to their ranks, it seems advisable to

sketch out both parameters of the discussion, a sampling of

the various theories that have been set forth, and then propose

a new, potential classifications.

Therefore,

this dialogue will start at a point with the most logic, agreement,

and tradition: The Golden Age. Some sources, including The

Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide, consider there to be

a Platinum Age, which predates the Golden Age. However, few

if any, superhero titles populate this era; in fact none of

Overstreet's "Top 10 Platinum Books" resemble anything

that would be considered from the superhero genre (1999: 70).

For

the full article, follow

this link!

|

In

his book How to Read Superhero Comics and Why, Geoff Klock

notes this moment, saying:

In

his book How to Read Superhero Comics and Why, Geoff Klock

notes this moment, saying: