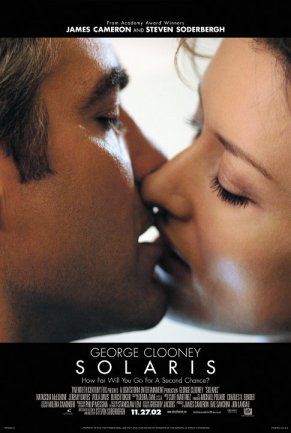

There is a tiny part of me that hates Solaris, Steven

Soderbergh's latest, not for any fault of the film but because

I know that in the future, I will have to endure at least

one dirty failed philosophy student of a stoner cornering

me at a party and informing me how deep this picture is if

I "really think about it."

I'm not against thinking about movies, and Solaris

certainly asks to be pondered; I just don't like the superior

position one takes in the phrase "if you really think about

it." The problem is, Solaris is a "really think

about it' kind of flick, and for that I love it.

In his third picture with George Clooney, Soderbergh pulls

off an actor-director team-up trilogy that rivals the Russell-Carpenter

films of the early Eighties. When boiled down to its basics,

Solaris comes right off the shelf of classic Star

Trek -- while in orbit around a newly discovered phenomena,

crew members are visited by long lost loved ones, but to quote

one of the crew, "I could tell you what's happening, but I

don't know if that would really tell you what's happening."

Soderbergh isn't as interested in stories to tell as he is

in how to tell them.

The picture masterfully stitches one languid scene to the

next with daring ellipses that thrill and challenge. It starts

at full speed in a sequence that proves an opening can leave

an audience breathless without the typical action film two

seconds from the climax gimmick.

Clooney plays psychologist Chris Kelvin, who receives a

message asking him to come to the Prometheus, a space craft

in orbit around Solaris. Solaris ripples and glows with fluid

and electricity, at times looking like a Fantastic Voyage

style view of the inner-eye and also invoking a Discovery

Channel animation of synapses firing. Kelvin arrives at the

Prometheus to find only two living crew members, one terrified

(Viola Davis) and one tweaked (Jeremy Davies), and a cold

storage full of bodies.

Sure, with this set-up your average sci-fi picture would identify

some evil cause behind the crew's loss of their senses and head

us down to the planet surface for a final showdown with whatever

entity would dare mess with the heads of hard working earthlings.

But this ain't your average sci-fi picture. Solaris

is much more 2001 or Silent Running than it

is Star Trek or Alien. This picture is more

about memory and grief than it is about space ships and blasters.

The story bounces back and forth between the goings on onboard

the Prometheus and Kelvin's past on a decidedly non-futuristic

Earth. No year in the future is specified, but mankind has

obviously mastered that whole faster-than-light-speed thing,

and the TVs are much cooler, but people still open doors with

knobs and hinges by hand, and prepare their own dinners without

the replicators or nutrient pills we've been told are inevitable.

On Earth Kelvin loved and lost Rheya (Natascha McElhone),

but on the Prometheus he wakes up to find her in his bed.

While Solaris is a remake of a Russian film based

on a Stanislaw Lem novel, Soderbergh's script and direction

make the material his own, as one would expect from one of

the most interesting and talented directors working today.

The picture brings to mind last year's Vanilla Sky,

another American remake of a foreign language film by one

of the great directors of today.

Sadly, Solaris is probably doomed to the same fate

as that under-appreciated film. It will play multiplexes,

even though it's an art house flick, because it happens to

have a multiplex budget. This weekend, turkey-drowsy families

will go to see the new George Clooney flick, urged by an overemphasis

on producer James Cameron's thankfully unnoticeable involvement,

and will be asked to digest more than they bargained for.

I hope I'm wrong and this film is embraced, but I'm sure it

will lose its Oscar nom spot to My Big Fat Greek Wedding.

Soderbergh proves that science fiction doesn't have to be limited

to action pictures set in the future. That, more interestingly,

the progress and possibly even the evolution of the human race

won't necessarily answer the questions about where we came from

or why we're here, but that progress might make those answers

seem a little more urgent. The farther we go along, the more

we need to know will grow exponentially.

Structurally, the film bears this out, as each answer we

are given just makes us ask ten more questions. The questions

range from the simply intriguing, "Is an imaginary friend

any less valid than a real one?" to the complexly weighty,

"Are we created in God's image or he in ours? Or neither?

Or both?" Solaris poses these questions in such a form

that they are really just variations on a theme.

The entire film plays around these problems of identity

and identifiers, of creators and created, with such complexity,

yet never becomes heavy-handed or obvious. Some of the audience

may be turned off by the picture's reluctance to dish out

answers, but that very reluctance makes Solaris the

treasure that it is.

Solaris succeeds with an act that usually spells

disaster for a film: that of rumination. The film plays its

one theme in so many different ways it isn't obvious how well

everything ties together. Soderbergh has once again jumped

the tracks of genre just as he did with The Limey and

Ocean's 11, both following and recreating what we know

about these old friends, just as the characters high above

Solaris do for themselves. It's really deep.

If you really think about it.

Rating: