|

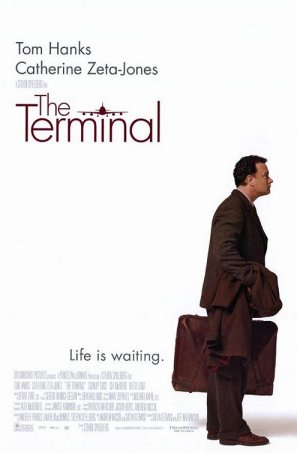

The

Terminal

Once upon a time, in a far away land called

New York, a charming little story unfolded about a man without

a country who wanted to visit America. In the real world,

the story wasn't so charming, as it involved political upheaval

in his homeland, and mass slaughters always take the bloom

off of cute fables. Then bureaucrats have to get involved

in this sort of thing, and they're not so much evil as just

annoying. That, too, makes it hard to keep things light.

So Steven Spielberg, a director that once

knew how to gloss over such things but has now become a

serious important director, can't quite make The

Terminal work. Seriously, twenty years ago when he cared

more about entertaining the crowd than teaching them a lesson,

this movie would have glowed.

But twenty years ago, Spielberg might not

have been able to have Tom Hanks and Catherine Zeta-Jones.

They were around, but nobody lined up to see them.

Thankfully for The Terminal, people

line up to see them now, and they work hard to redeem some

grim direction and quite honestly sloppy nonsensical story

editing.

At its heart, the film has an interesting

story, and it's loosely based in a real-life event. Viktor

Navorski (Hanks) arrives at LaGuardia Airport from the fictional

country of Krakozia, only to find his passport unacceptable.

It seems that while he was in the air, his country suffered

a bloody government coup, and to the United States, Krakozia

may now be history. Stuck as a man without a country, Hanks

cannot return home, but neither can he actually leave the

airport terminal and enter New York City.

The airport officials, now associated with

the Department of Homeland Security (strangely treated as

if this is the way it has always been - forgive the thoughtcrime),

actually hope that this isolated visitor will just break

the law and escape. Then he will be someone else's headache.

Unfortunately for them, he respects their authority, and

makes the airport his home.

What

follows is an uneasy mixture. At times, it's fascinating

to see how he survives, creating a living space in an area

of the terminal closed for renovation. (As an afterthought,

the script makes him a building contractor in Krakozia,

and he's also better and more industrious than the crew

actually working on the terminal.)

But

there are also scenes in which his cleverness seems like

part of a psychological experiment on a monkey, with the

security guards watching him on their screens and marveling

at how he's worked out how to get a little money.

If there is any condescension toward this

stranger in a strange land, it does not come from Hanks.

With almost any other actor, this role would seem like Oscar-baiting.

Surely, he jumped at the chance to demonstrate a facility

for a vaguely Russian accent. But what carries him through

is his expressiveness as an actor. What happens to the character

sometimes feels forced, but Hanks can make us believe it

with a look, especially since for at least half the movie

his English cannot even qualify as fractured.

Too

much of the movie, though, feels forced because Spielberg

keeps undercutting his ability to charm us. As with Catch

Me If You Can, you're seeing a director fight his

instincts, forgetting that if you build a story right, no

matter how improbable, we want to see more. So a

cute side romance between a food worker and an immigration

officer isn't just on the side; it's practically invisible,

so we're jumping from an awkward courtship with Hanks in

the middle to a wedding. But Spielberg seems so unsure of

its value that we can't feel anything for it, yet there's

a dynamite throwaway "reveal" scene that proves that dangit,

this guy can direct.

The two sides to the director struggle

too hard. For every scene that charms us, he has to counterbalance

with one that makes a dubious political point. We almost

see what a great place America is, or can be, but he cannot

resist reminding us that it's also full of assholes. Hey,

we can get that easily outside of the theater, Steven.

Trapped in this dichotomy is Zeta-Jones.

Conversely, she gives one of the strongest performances

of her career, precisely because it's so gentle. As the

love interest Amelia, she plays a flight attendant facing

fears about age and loneliness. Stuck in a destructive relationship

with a powerful lawyer (Michael Nouri, an underutilized

actor), she bides her time with history books while waiting

for the page that says their affair can resume. This hard-edged

actress drops the veneer, becoming believably fragile and

vulnerable in a way her previous roles hardly hinted she

could do.

And then the serious director jumps in

and starts tearing down all the innocence and fairy-tale

nuance that the crowd-pleaser set up. It's hard to give

in and really like this movie, because we cannot trust it.

That applies even to the ending; it may be real, it may

be adequate, but it keeps us at a distance.

That's a mistake, because all the elements

are here for us to love. You can temper the sentiment, pull

it back from mawkishness, without building a wall between

it and the audience. For some reason, Spielberg has not

figured out how to do that yet.

Rating:

|