|

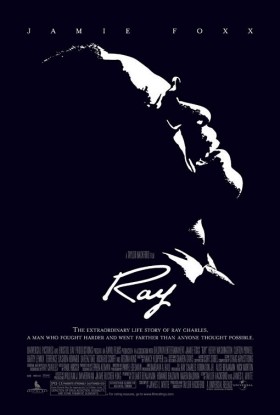

Ray

Late in Ray, Ray Charles suffers an

hallucination in which he can see. At that moment, he takes

off his sunglasses and reveals himself to actually be actor

Jamie Foxx. It's a startling and almost spell-breaking shot,

because you can absolutely believe the hype. Foxx so effectively

submerges himself in the life and character of the troubled

singer that you forget that he is, after all, just an actor

playing the man.

The performance moves beyond mere impersonation.

Every tic, every trait, just seems natural. Prosthetics

help a bit, forcing Foxx's eyes shut, but the heart and

soul come from within. So it's really a shame that the script

falls prey to so many false moments; Foxx himself never

has one.

Written by James L. White and director

Taylor Hackford, the story covers Charles' rise from young

honky tonk pianist to groundbreaking entertainer almost

consumed by his addiction to heroin. That in itself cannot

be considered trite, because, after all, it is true.

But the man's demons get literal manifestation

in the memory of his drowned brother, a disturbing image

that repeats too often and somehow gives a hollow excuse

to why Brother Ray got a taste for smack. To Hackford's

credit, the film at least reveals the drowning early, but

also recognizes it as a weak point.

Weaker, still, is the overall lack of impact

of heroin use until the film's climax. Though Atlantic Records

chief Ahmet Ertegun (a welcome Curtis Armstrong) recognizes

the addiction, it never gets in the way of recording. Charles

just has "the junkie itch." In a few spots, Hackford elides

some swipes at how the entertainment industry turns a blind

eye to drug use, but it's so subtle a lot of audiences may

miss that anything was wrong at all.

Charles

overcame many prejudices and predators, and the film does

include all that. But the script also makes some moments way

too pat, especially in portraying the development of his musical

style. You can buy that maybe, just maybe, the song "I've

Got a Woman" found inspiration in his falling in love with

his eventual wife, Della Bea (Kerry Washington). However,

the scene in which he discovers "Hit the Road, Jack" is almost

a parody of a movie moment - especially since the final credits

reveal somebody else wrote it.

Still, Hackford has a master director's

touch. The visuals soar even when the script bumps the road.

Despite its weaknesses, the film moves at a brisk clip that

makes its nearly three hours seem much less.

Part of

the credit has to go to Foxx, but the rest of the roles have

been cannily cast as well. Bokeem Woodbine quietly pulls focus

as the saxophonist "Fathead," a stalwart sideman for Brother

Ray for years. As Della Bea, Washington is nothing less than

luminous, a fine contrast to Regina King as Charles' first

Raelette and second major mistress, Margie Hendricks. (Even

there the script fails; the issue of his infidelity rears

its head then disappears. The guy had a bastard son and Della

Bea just shrugs. No man is that charming.)

The smaller roles, too, have been cast

for quirks. In addition to Armstrong getting the rare chance

to play something close to normal, Warwick Davis shows up

as an emcee at the first jazz club Charles plays for. It

could be an historically accurate casting, but it's good

to see the guy sans fur or leprechaun suit, actually

acting.

It is that acting that makes this film

absolutely worthwhile. Sure, the music's good, too, with

Ray Charles himself having re-recorded several vocals before

his death this year. But we've had his albums for years.

Now we have Foxx's performance, the latest in a string of

good roles for him, but the one that will finally make him

a star. Collateral made me think he was; Ray

puts him in his place.

Rating:

|