|

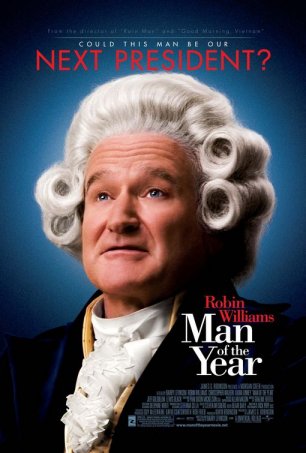

Man

of the Year

Man of the Year

isn't funny; it's angry. Writer/Director Barry Levinson

has seen a system corrupted, if not outright broken, and

he's not going to take it anymore. Unfortunately, it's not

the kind of anger that stirs people up. Consider this, as

Woody Allen once scripted, a devastating letter to the New

York Times.

Ads make it out to be a feel-good comedic

fantasy about a political comedian winning the Presidential

election. Sure, that's a wish fulfillment for those that

consider Jon Stewart the sharpest political mind in the

country. Though Levinson has built this vehicle around Robin

Williams, the film actually intends to be a political thriller/satire

that happens to be about funny people, instead of being

actually funny.

Even the manic Williams does his own material

at half-speed, which doesn't blunt the edge of his observations,

but definitely dulls the delivery. Part of that comes from

his character Tom Dobbs' initial conviction that if he's

going to run for President, he's going to talk seriously

about the issues for once.

Though that drives his staff crazy, begging

him to cut loose with his cutting wit, none of it really

matters. It's all just set-up for the real plot. For the

first time, the entire nation will be using the same computerized

voting machines, and software programmer Eleanor Green (Laura

Linney) has discovered a flaw that consistently gives the

election to the wrong candidate.

Naturally, this means that Eleanor's life,

or at least her reputation, are in danger. It's too close

to the election to admit that the machines don't work correctly.

Cue ominous music and a woman on the run, especially once

the machines inexplicably elect Tom Dobbs.

To top off the roller coaster tone, Green

and Dobbs find themselves attracted to each other, so in

between scenes of suspenseful stalking by her former employers,

we get gentle romantic comedy. When Robin Williams does

gentle romantic comedy, he can't help but be cloying.

And cloying just doesn't work when you've

got sinister lawyers (Jeff Goldblum), break-ins, druggings

and mysterious "car accidents" that aren't played the slightest

bit for laughs. Shamefully, Levinson even puts Dobbs on

Saturday Night Live and forces Tina Fey to do an

irony-free moral moment. Not only is it one of an endless

parade of pundit appearances to add verisimilitude, Fey

just doesn't do irony-free.

Throughout the film, Levinson keeps playing

against his actors' strong points. He puts Christopher Walken,

as Dobbs' manager, in a wheelchair, sharply reducing his

quirky physicality. As a plot point, it serves little purpose

beyond an opening scene red herring. Though Goldblum can

do evil really well, Levinson actually writes the character

as little more than misguided. It's a disservice to both

the actor and the plot.

Aside from Williams forced into a Jon Stewart

suit, the biggest waste of talent is in Lewis Black. One

of the best (and funniest) ranters alive, Black plays Dobbs'

head writer Eddie Langston, and ends up whining more than

releasing comedic vitriol. Levinson uses Black to harp on

the movie's themes, but doesn't allow the ideas to be expressed

with any wit; it's just repetitive and ham-handed.

Black's presence also triggers an area

of unbelievability. In a world that acknowledges The

Daily Show, it's difficult to swallow the idea that

a writer for a rival program could look and sound like Lewis

Black (shot to prominence by his appearances on The Daily

Show) and not have someone comment on it.

Then again, all Black and Eddie Langston

really have in common is Levinson's anger. It's a righteous

anger smothered by a possible fear of being too on the nose.

Everything gets softened. The voting machine scandal really

is just an accident, not a conspiracy as some believe happened

with Diebold's machines in real life. The rival presidential

candidates are bland but decent, and despite Dobbs' antipathy

for them, we have no reason to think they aren't

trying to be good leaders.

So

Man of the Year should inspire the same kind of soft

anger, at a movie that has a good idea at its core, good

talent and good timing but still can't pull itself to its

feet.

A talented

filmmaker like Barry Levinson should be better at picking

which tools he's going to use to make such a personal and

important statement. Working with Williams should have knocked

this out of the park; Levinson was one of the first directors

to figure out how to use Williams correctly in film with

Good Morning, Vietnam.

We should be angry

at exactly the same things Levinson is, but we should also

be angry that we didn't get a film that effectively explained

why nor even turned out particularly entertaining.

Rating:

|