|

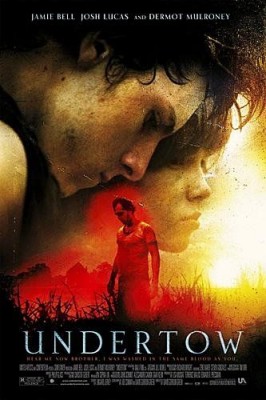

Undertow

David

Gordon Green is the type of director that revels in simplicity.

Sounds easy enough, but it is far more complex than that.

The complication comes from the manner in which he approaches

the simplistic, and that is to treat it as if it were the

only thing that truly mattered in the universe. Undertow

marks his third film, all of which feature the rural landscapes

of the South as their backdrop for tonal explorations of

adolescent growth, and the pains associating with expression

of feeling.

Everyone

has been there. That consuming sense of urgency that extends

beyond the means of one’s own flesh, as if the skin

would tear wide open if it refused the growth spurts imposed

upon it.

Strikingly,

with each installment Green seems to raise the ante a bit,

and delve deeper into the true horror and beauty that makes

up humanity. As with George Washington and All

the Real Girls, Green explores the complexities of

expression in a beautifully understated wash of mood and

ambiance, never crossing the line into the obscure, but

dwelling fastidiously in the ebb and flow of the surreal.

This

time around, the focus is on two brothers. Chris (Jamie

Bell), the rebellious older sibling, provides us with our

glimpse into his world. We observe aspects of his life in

snippets, sometimes without the details preceding or following

specific events. It’s almost as if he is recalling

these memories for us to witness firsthand.

It’s

said at one point that “sometimes it’s the strange

moments that stick,” and this is profound. Green emphasizes

this with aptly placed freeze frames throughout the film,

framing incidents as they occur and etching them onto the

screen as they would in Chris’ mind.

As Chris

inches his way deeper into trouble, his younger brother

Tim (Devon Allen), seems to be heading for danger in his

own way. Frail and bordering malnourishment, Tim refuses

to eat the food prepared for meals, but secretly devours

mud and paint chips, to the point of making himself physically

ill.

The

third in the family is paterfamilias John (Dermot Mulroney),

a quiet yet stern man who seems at odds with Chris’

rebellious nature, yet fails to see how his affection for

Tim seemingly exacerbates the problem. Being older and more

physically fit, Chris is handier around the house tending

to the pigs and mending the roof while Tim is left to poison

himself.

John

mourns the loss of his wife, and at one point explains that

following her death he decided to uproot the family and

move to the middle of nowhere to “live like hermits.”

The hint of a secret, some sort of regret from the past,

is intertwined with remorse over his loss, and it leads

to bigger issues when his own brother Deel (Josh Lucas)

arrives on parole from prison.

With

his arrival, Deel opens up old wounds and also peaks the

interests of Chris, who seems keyed into the skeletons in

his father’s closet surrounding a collection of priceless

Mexican gold coins. The dynamic between both sets of siblings

are intended to compliment one another, yet Green has woven

a thread of morality into the film early on which underlines

the developments between all involved.

This

“message” is far more subtle and in line with

Green’s intentions than merely inflicting yet another

life lesson on his audience. In the opening sequences of

Undertow, Chris’ feelings for a young woman

he fancies gets him into trouble and he ends up skewering

his foot on a board with an errant nail. This

is naturally cringe-inducing, but the ingredients used in

this sequence resonate in small ripples throughout the rest

of Chris’ arc. His tenacity to stand firm is depicted

in the manner in which he walks away with the board still

attached to his foot.

Chris’

disruption of Tim’s birthday party is something he

defends when his father calls him on his actions. He protests

John’s favoring of Tim, and spews hurtful truths that

are both intended and typical of teenagers his age, yet

the scenes never succumb to melodrama.

What

comes of these sequences is told through actions, but not

as one might expect. After the police return the board in

question to Chris, he decides to make use of the wood itself

by fashioning a wooden airplane to give to Tim for his birthday.

The gift is both redemption and apology incarnate, and illustrates

his feelings for his sibling despite the disdain he may

feel about his own treatment in the house.

It would

be a mistake to delve deeper into what unfolds for Chris

and Tim, because the film deserves to be seen, not dictated.

Those

willing to take a chance on Undertow will be welcomed

by a pastiche of memory, both sullied with dirt and grain,

yet beautifully rendered in fondness and affection. Lucas

and Mulroney are surprisingly cunning in the film, wrestling

with a past that each feels justified in while Bell and

Allen manage to steal the show with their sincerity. Included

in Green’s many strengths is his ability to coax intelligent

and cogent performances from his youthful actors.

Despite

the lack of rare gold coins in most families, everyone is

sure to have experienced differences of opinion regarding

various events within a family history that have either

divided or united members together. Green has managed to

fuse these tiny dramas together into something larger in

scale, affecting all of humanity individually and universally

at once.

Rating:

|