|

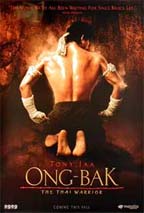

Ong-Bak:

The Thai Warrior

Wow.

Prachya

Pinkaew’s debut feature Ong-Bak is by no

means brilliant, but damn if it isn’t entertaining

throughout. Pinkaew’s film hits all of the requisite

touchstones one expects from the action martial arts genre

yet somehow manages to work despite the usual trappings.

How you ask?

Two

words: Tony Jaa.

Yes,

the claims being touted that Jaa is the biggest thing to

hit the martial arts scene since the sliced bread that was

Bruce Lee are grandiose, but rest assured, he will amaze

you.

The

typical formula for action films such as Ong-Bak

usually consists of a paper-thin plot that is constructed

solely for the self-serving purpose of acting as a showcase

for down and dirty action stunt sequences. Ong-Bak

is certainly no different, but it does hold a few pleasant

surprises that cause the film to rise above and beyond the

rest of the crop on occasion.

For

instance, when a Bangkok street thug named Don visits the

peaceful religious village of Nong Pradu to persuade one

of the locals to part with an antique religious artifact,

we get a clear look at just how steadfast the locals are

in their beliefs. There is no “right price”

for such an artifact, which the local explains is intended

to be handed down to his son once he is ordained.

This,

of course, provokes Don, so he steals the head of the Buddhist

statue of Ong-Bak, representing their local deity. Such

thievery just happens to coincide with Boonting’s

(Tony Jaa), Ting for short, completion of his Muay Thai

training.

His

trainer insists that he never use the fighting art form,

and it is explained that he killed a man in his very first

“ring match,” an act which prompted him to become

an ordained monk. Everyone knows the drill, fight for good,

and better yet, don’t fight at all. It almost bores

along too far in Ong-Bak, except for those few

saving graces mentioned earlier.

They

come in small doses, but it’s enough to keep things

fresh. First off, there is a scene depicting Ting’s

departure from Nong Pradu. Don had moronically left his

Bangkok address in case anyone had any second thoughts about

parting with any valued artifacts, so naturally someone

must be sent to retrieve the head of Ong-Bak. The village

elects Ting and wishes him luck on his journey by giving

what they can to aid in his quest. Their gifts are small

yet sincere, a few coins here, a bill or two there, a ring

passed down after the death of a loved one. To say that

Nong Pradu is poor is an understatement, yet they give despite

their own personal woes. It’s touching in a genuine

sort of way, and the scene just narrowly evades the schmaltz

factor it could have easily relished in.

At its

core, Ong-Bak is a redemption tale, and again this

is common amongst films of this ilk. The interesting spin

on this particular redemption tale is that Ting is not the

character in need of salvation. Before leaving Nong Pradu,

Ting was asked to deliver a letter to a wayward son in Bangkok

by the same local whom Don had badgered earlier. The man’s

son is Hum Lae (Petchthai Wongkamlao), who left Nong Pradu

to avoid life as a monk and instead became a grifter on

the streets of the big city. Hum Lae now goes by George

in order to fit in and leave his “hick” roots

behind him. He runs scams with Muay Lek (Pumwaree Yodkamol),

a schoolgirl who hustles to pay tuition.

Ting

meets George who wants nothing to do with the quest until

he realizes that Ting possesses a bag full of money. Usually

there would be a scene involving the hero becoming forced

to participate in fights against his will, or for the greater

good of some other hapless victim. That scene comes in time,

but the reveal of Ting’s abilities is far less forced,

yet another one of those subtle touches mentioned earlier.

After learning that George has stolen his money, Ting follows

him to a local fight club and confronts him. George points

to the betting booth when asked about the money, and Ting’s

naiveté leads him into the middle of the ring, a

gesture that indicates a challenge. Ting disposes of his

opponent, the current reigning champion, in one single blow.

This not only serves as a means of exposing his talents,

it also costs the local crime boss Kum Tuan (Sukhaaw Phongwilai)

a large sum of money in the process.

|

As the

plot unwinds, we learn that Don is actually working for

Kum Tuan, who is gathering up priceless religious artifacts

in plans of smuggling them for an undisclosed reason. One

would assume profit, but the plan is not clearly laid out

and this turns out to be another plus. We know he’s

bad, that will suffice. Kun Tuan wants Ting to fight for

money, and Ong Bak is the key to making him do so. Anyone

can see where this is headed, and it works out well enough

even if it takes a bit of time to get where it’s going.

There

are a few subplots so poorly developed that they need not

be mentioned. Yet despite these trouble spots, the key reason

anyone should even bother to see this film in the first

place is to bear witness to Tony Jaa’s expert displays

of Muay Thai form and prowess. Attempting to describe these

sequences would do injustice to them, so there is little

point in going there at all. The low-budget aesthetic only

adds to the realistic feel of the rather unreal spectacle

on screen. The grainy stock used by necessity, not choice,

makes it feel like you may be watching something on par

with a martial arts snuff film, even though it never really

delves to such dark levels in content.

When

you witness Jaa’s escape from a local street gang

through a small market in Bangkok, you will be hard pressed

to sit still in your seat. Each feat is replayed from different

angles, not just for effect or to make it look cool, but

to add perspective to what Jaa is actually accomplishing

on screen. These sequences are seamless, and well worth

the cost of admission for fans aching for a fix.

Rating:

|