|

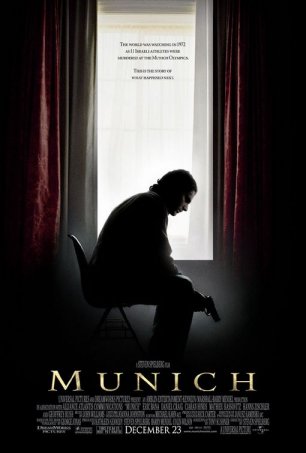

Munich

Steven

Spielberg has delivered. His profound take on the sci-fi

genre in the Tom Cruise starring vehicle War

of the Worlds pales in comparison to Munich,

and in many ways, everything the director has ever touched

seems to be fair game for re-evaluation. Munich could

very well be the director’s defining moment.

Where

War of the Worlds entertained, the film still succumbed

to the usual Spielbergian trappings by retreating back into

safe, family friendly territory before the closing credits.

Anyone who has seen the film knows the moment that spoiled

the fun.

Munich

seemed ripe for one such moment. In fact, with his track

record it’s a wonder Spielberg didn’t allow

the film to veer off into that all too saccharine world

full of schmaltz and happy endings.

And

with touchy subject matter like the Israel’s response

to the Black September attack on the Israeli team in the

Munich Olympic compound in 1972, one wrong step for the

director could have spelled disaster.

Fortunately

for everyone involved, Spielberg had his approach for the

film fully fleshed out, and what audiences will find is

a thought provoking, unrelenting look at the methods used

by modern governments to combat terrorism. For those quick

on the uptake, this does entail allusions to September 11th,

but that isn’t all that Munich is.

To frame

his statement, Spielberg tells the story of a young Israeli

intelligence officer named Avner Kauffman (Eric Bana) who

is tapped by a Mossad officer named Ephraim (Geoffrey Rush)

to embark on an extremely important mission in the wake

of the Munich massacre. Avner is instructed to join four

other men to form a hit squad, charged with hunting down

a list of suspected Black September masterminds behind the

tragedy.

They

are instructed to leave all family and contacts behind and

work outside of the government in anonymity. For Avner,

this means leaving behind his pregnant wife and mother to

serve a country he has always felt and sense of dedication

towards. Employing the most classic of Spielberg thematic

devices, we are given evidence that Avner’s father

also served as a Mossad officer, which meant being away

from home for long stretches of time, at one point imprisoned

while serving his country.

This

of course suggests that Israel has become a surrogate father

for Avner, but suffice it to say, this is not overstated

or played at the levels of cheese that it could have been.

In fact, Avner’s own issues with impending fatherhood

provide a subtle enhancement of the theme, endearing at

the darkest of moments, providing a perfect blend of affection

and sheer dread.

Avner

is given strict instructions with a detailed list of names

to eradicate and nothing more. As the hit squad sets to

work tracking down their targets and making contacts for

information, they slowly begin doubting the underlying purposes

behind their mission, and the means with which they are

instructed to carry out their mission.

It is

probably wise to refrain from digging into too many intricacies

as far as plot and message are concerned because a film

as important as this is worth discovering. However, Spielberg’s

approach to the film is nearly as vital as the subject matter

at hand. Taking place in 1972, the film actually lends a

look and feel as familiar as any entry from that time period.

Cinematographer

Janusz Kaminski, who has worked with Spielberg several times

before including on Schindler’s List, paints

with seventies genre clichés without ever allowing

the line of forced inference to be encroached upon.

Sure,

anyone can select a film stock with more grain for effect,

but everything from framing to shot choice is spot on in

recreating the tone necessary to make the film feel grounded

in the past. Even the editing work in both the film and

sound departments helps to flesh this aspect out to a greater

degree.

Take

for example a sequence in which a bomb has been rigged underneath

the mattress of a target and members of the hit squad are

stationed outside waiting for the sign to trigger detonation.

As Avner is stationed inside the hotel, waiting to send

out the signal, Steve (Daniel Craig) is waiting in the car,

all the while singing “Papa Was a Rolling Stone”

in a nervous yet subdued manner.

Cross

cutting between events occurring all around, the sequence

loses its footing, weaving creepily into a chilling spiral

of tension and urgency. It is nearly reminiscent of some

of the aural experimentations found in Francis Ford Coppola’s

The Conversation.

Munich

is the result of a filmmaker with a message firing on all

cylinders. Sure, he may have knocked one out of the park

with War of the Worlds, but still managed to fall

short in the tail end of the third act of that film. Here,

Spielberg manages to refrain from such dalliances, delivering

a film as good, if not better, than anything he has ever

offered before.

Rating:

|