|

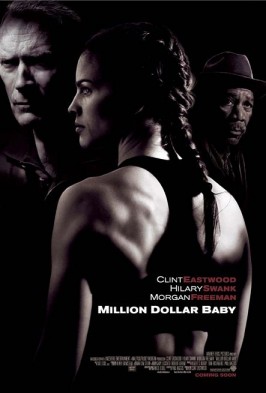

Million

Dollar Baby

The biggest story this awards season will surround Clint

Eastwood’s knockout left cross sucker punch from seemingly

out of nowhere, Million Dollar Baby. There is just

no two ways about it, this film is a surefire sparkplug

that simply cannot be ignored. Mystic River surprised

a lot of people, but nothing, and I mean nothing, could

possibly prepare you for this film.

On the

surface it looks harmless enough. In fact, on mere pitch

alone it is almost easy to see why a studio like Warner

Brothers would shy away from financing a film whose central

characters are steeped in boxing culture. Add to this the

fact that the central fighter is a female played by Hillary

Swank and you can rest assured that the suits smelled a

“female Rocky” on their hands. The thing they

forgot to factor in is that the man pitching the film was

Clint Eastwood, a man not known to “go quietly in

the night.”

Stepping

aside from the whole scenario, I must be up front and admit

that I’m not, by any means, a huge fan of Clint Eastwood

“the director.” He’s had his share of

hits in my book, but never really seemed to “gel”

for me behind the camera. As an actor, he has the stuff.

I’ve just always put his role as a director as a second

tier move from a screen legend in the business. Never mind

the twenty-plus films he’s directed, it never really

affected me.

Million

Dollar Baby, however, has me rethinking this position.

Granted, his previous work is what it is, and that’s

just not going to change for me. Yet Baby is just

so good that you simply cannot dismiss the man in the chair.

His paws are all over this one and it’s nothing short

of pure cinematic gold.

Let’s

plow through some basic plot points to set up the gist of

the film, because to move past any of the general stuff

would really, truly, rob you of a genuine experience. We

are introduced to “the best ‘cut man’

in the business,” Frankie Dunn (Eastwood), whose latest

fighter “Big Willie” Little (Mike Colter) has

been two bouts away from a title shot for the last two years.

We are given a peek into Frankie’s life and his philosophy

second-hand via his ex-fighter buddy Eddie “Scrap

Iron” Dupris (Morgan Freeman). Eddie runs Frankie’s

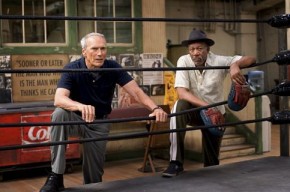

gym for him and serves as the narrator for our story. Freeman

is, quite possibly, the best voiceover narrator around,

yet I must admit that I grew concerned that his work here

may fall a bit too close to his work as Red in The Shawshank

Redemption. There is no need for concern whatsoever.

Freeman’s work as Eddie is a complete departure from

his work as Red. Simply put, the two characters couldn’t

be further from one another.

|

We learn

through a series of events, mostly surrounding his reluctance

to set up a title shot for “Big Willie,” that

Frankie is a protective trainer whose word must be final

because he is unwilling to sway from what he feels is right.

This opening conflict with “Big Willie,” his

interactions with a slick “money man” named

Mickey Mack (Bruce McVittie), and his eventual decision

to leave Frankie for a new trainer and the promise of a

title bout evolve slowly, yet they speak volumes in character.

Films

aren’t made this way anymore. Usually, early conflict

such as this is usually brought full circle in a “physical”

climax in the third act. Here the events within the conflict

shape decisions that the characters must make in the story

to come. For instance, if you stub your toe on something

while running around with no shoes on, you don’t take

an axe to the object you ran into, but the event may encourage

you to walk slower or be more cautious in the future.

Frankie’s

past remains shrouded in deep, painful, secrets. He attends

church more than anyone else in the parish and frequently

engages in biting debates with Father Horvak (Brian O’Byrne)

who insists that the only reason Frankie comes to mass is

to ridicule and harass the young priest. Whenever the ribbing

grows to be too much, Father Horvak asks Frankie whether

he has written his daughter yet, to which Frankie replies

“Everyday.” Horvak believes this to be a lie,

but the pain in Frankie’s eyes tell another story,

as do the letters marked “Return to Sender”

found under his doorstep everyday.

Here

is a safe way to illustrate the kind of depth Baby

exudes without spoiling the meat of the film. Frankie’s

interactions with Father Horvak, his cutting jabs at the

faith, seem to suggest a deeper relationship between the

two characters. Make of it what you will, but it would appear

that Horvak “could have been a contender” but

instead chose to pursue a life within the church. Perhaps

this doesn’t sit well with Frankie; we never even

know if the assumption is true or not, but the implication

exists and like everything else in the film it serves a

deep significance.

Of

course, Frankie is influenced against his will to take up

training tough Maggie Fitzgerald (Hilary Swank). Frankie

initially replies, “Girlie, tough ain’t enough,”

but later decides to give in because she is his only steady

paying fighter at his gym. The decision to shy away from

this development is critical, because expectations are both

met and discarded in Eastwood’s process of telling

his tale.

The

real treasure here is found in the way Eastwood does the

telling, in subtleties. He lets things lie as they are,

and this is a technique that is not often found utilized

by today’s directors. Perhaps some of this stems from

Clint’s own philosophy, or perhaps much of this approach

should be credited to ex-cutman turned author Jerry Boyd,

who under the pen-name F.X. Toole compiled the inspiration

for Million Dollar Baby, a series of short stories

entitled “Rope Burns : Stories From the Corner

.”

Surely

the manner in which Frankie copes was likely shaped from

Boyd’s accounts, but the presentation is what makes

Baby shine, and that credit goes to Eastwood entirely.

Rating:

|