|

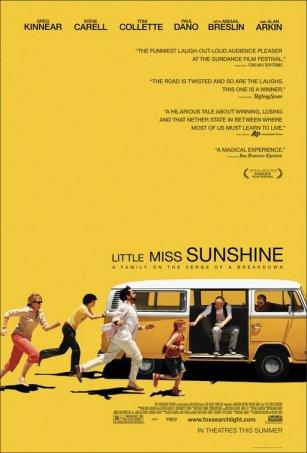

Little

Miss Sunshine To

dismiss Little Miss Sunshine as simply a formulaic

family road movie would be naïve, and yet one cannot

ignore that the film adheres to its formula driven roots

a little too faithfully at times. It’s not the use

of formula, but what you do with the formula, and screenwriter

Michael Arndt along with co-directors Jonathan Dayton and

Valerie Faris appear to be aware of this distinction.

Their focus is

trained on the human disposition of failure rather than

the tenets of a family growth narrative intertwined with

a road movie premise. The possibility, fear of, and realization

of failure is something that grips everyone to various degrees,

and anyone that says otherwise is lying through their teeth.

The film centers

on the rag-tag Hoover family, a gang of, for lack of a better

word, losers. Each of the Hoovers exhibits a different degree

of failure in their personal lives, and each one struggles

individually and collectively to either except or overcome

this feeling.

Olive Hoover

(Abigail Breslin), the youngest of the pack, has only one

goal in life – to win a beauty competition. Her brother

Dwayne (Paul Dano) wishes to be a fighter pilot, and has

designed a strict daily workout to condition for the task.

Inspired by Nietzsche, Dwayne has taken a vow of silence

until he achieves his goal, and resorts to carrying around

a pad of paper and pen to communicate.

Grandpa

(Alan Arkin) is coping with feeling that the bulk of his

life is in his past, so after being kicked out of his retirement

home, he has taken up training Olive for her beauty contest

performances while secretly snorting heroin to numb the

pain.

His son Richard

(Greg Kinnear) has his whole life ahead of him, but squanders

it away with his obsession over “winning.” Richard

has developed a plan for success titled “The 9-Steps

to Winning,” and he not only preaches the doctrine,

but to the chagrin of his family, lives the program as well.

Richard lives

in a world in which he perceives himself to be succeeding,

but refuses to realize that his boat is sinking with his

family aboard. Failure is one thing, but to be the last

to know about it is another. He hides the truth from himself,

and others, further deluding and obscuring reality with

each fib he tells.

Sheryl’s

(Toni Collette) dealings with failure are less obvious than

the others. Her feelings of inadequacy stem from her inability

to hold everything together. Repeat fast food fried chicken

dinners, and statements like “You’re the mom,

you’re supposed to protect her” cut her deeply,

and the fact that her brother Frank (Steve Carell) has recently

attempted suicide doesn’t help the matter.

Frank, as it

turns out, is “the world’s leading Proust scholar,”

but he isn’t initially perceived as such. Our introduction

to Frank follows his release from the hospital, and we are

given the feeling that this isn’t his first attempt

at killing himself. Whether or not that is true remains

unexplored, but it becomes irrelevant in the end.

This

is all setup, and these tics and subplots all come to fruition

throughout the film. Some are more obvious arcs, as you

may be able to tell from the setup above, but for the most

part the importance isn’t in the obvious nature of

the pending arc, it’s in the execution.

Dayton and Faris

have a knack for making one feel uncomfortable with each

obvious turn. There were several moments in the film, one

that pre-empts the beginning of the third act specifically,

that left me contemplating whether or not the film would

ultimately work for me.

Overall, it does,

but it is to the credit of the subtle character work, acting,

and the inference of subtext. For instance, Grandpa’s

insistence that Dwayne get laid more as a 16-year-old boy

is absurdly and awkwardly funny. Richard’s objections

to the brash discussion of sex, despite Grandpa’s

insistence that Olive’s headphones allow them to speak

frankly without her hearing, are hilarious and well timed.

This diatribe

could have been played for nothing more than laughs, but

instead it segues into a sequence at a diner in which Olive

decides to order a bowl of ice cream, and Richard obtusely

re-enforces the constraints society places on young women

in regards to beauty and their bodyweight.

As crude

as Grandpa’s delivery was, his rant about sleeping

with as many women as you can exhibits the underlying message

of living life to its fullest before it's too late. Richard

defends womankind by objecting to discussing this truth,

yet re-enforces the sexist undertones of Grandpa’s

diatribe in the diner to the very person he was attempting

to protect to begin with. Ultimately, he doesn’t want

to see Olive lose, but he goes about this the wrong way

and for all the wrong reasons.

These characters,

although they get stuck doing some pretty outlandish stuff,

are ultimately performed and written as real people. I have

a few issues with some of the more convenient beats in the

film, but ultimately it retains a comedic feel while never

fully shying away from the dramatic entanglements of reality.

The performances here are all exceptional, so much so that

it almost feels wrong to single anyone out.

The

themes are heavy at times, but the important thing is they

are never heavy handed. They may come to fruition in a convenient

or obvious fashion, but the film never preaches. In fact,

these themes sink in over time.

Following

the screening I couldn’t formulate a gut reaction,

and found myself reflecting afterward, internalizing much

of it, and even embarrassing myself with simple oversights

and mistakes while leaving the parking garage and pumping

a tank of gas.

The

funny thing is, the more one dwells on failure, the more

frequently they tend to fail. Someone should have probably

told Richard this sooner in life.

Rating:

|