|

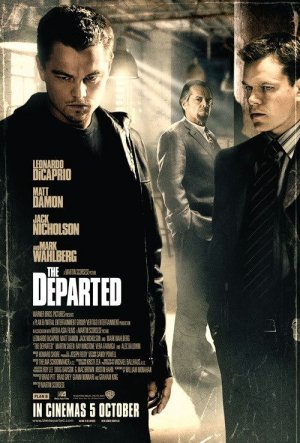

The

Departed

Forget about Gangs of New York and spare me all

talk of The Aviator.

It always felt wrong to watch Martin Scorsese’s yearly

vie for a gold statuette.

Ordinarily,

remakes of Hong Kong films don’t sit right with me.

Oh the irony, that studios look East when seeking “something

new” for audiences to cut their teeth on only to ruin

them with sad and tired Western tropes in the process of

pillaging…er, adapting. So why does Scorsese get a

free pass when remaking Wai Keung Lau and Siu Fai Mak’s

Infernal Affairs?

Simply

put, Infernal Affairs was a troubled effort with

one thing in its corner – an excellent idea built

upon the ground laid by Scorsese himself. The notion of

corruption and covert dances between police and gangsters

is titillating, but the original film crumbles under the

weight of its own premise. However, Scorsese’s film

works.

Screenwriter

William Monahan transplants Infernal Affairs from

Hong Kong to the streets of Boston, and infuses it with

a sense of regional edge. The film still centers around

two police cadets who embark on very different paths, yet

Monahan’s approach to these intertwined characters

crackles with Mamet-speak and Scorsese’s direction

– a comfortable step forward on the foundation laid

by the director’s dalliances in Italian mafia films.

The

key for any Scorsese fan is the use of some of the director's

more notable thematic elements, many of which are present

even if to a lesser extent than perhaps desired. Leonardo

DiCaprio’s Billy Costigan battles familial duty while

straddling class lines, while Matt Damon’s Colin Sullivan

is haunted by his own sense of morality and faith.

Religious

imagery stalks Colin as he moves from a former altar boy

to a member of Frank Costello’s (Jack Nicholson) fold.

Abandoning aspirations of a life of the cloth, Colin enlists

in the police force and quickly excels through the academy

under Frank’s tutelage. He makes plainclothes directly

out of the academy, and is quickly assigned to a special

crimes task force unit. Frank provided Colin with guidance

and in return he has a man on the inside of the police department

– not a bad commodity to have when you are the kingpin

of an Irish gang.

Billy,

on the other hand, has only ever wanted to do right, but

has felt compelled to maintain a tough guy image when being

passed back and forth between parents who live on opposite

ends of the class spectrum. Life has continually beaten

him, his family and most of the people around him, into

the ground. We watch him uncomfortably tell off his uncle

while his dying mother succumbs to her illness in a hospital

bed.

He grew

up in a family rooted in crime, and his dreams to become

a police detective are stymied because of it. Instead he

is offered the opportunity of a turncoat. He would be failed

out of the academy and sent off into the streets where he

will be picked up for a small crime large enough to land

him a respectable amount of time in jail. Once out, he is

charged with one mission – infiltrate Costello’s

gang and report back from the inside.

Scorsese’s

version of the tale is far less convoluted than the original,

but what he adds are layers that enhance the tone and theme

of the power struggle at hand. The Departed is

not simply about two men forced to go against the grain

of who they believed themselves to be, it’s also about

two men caught up in the pretense of duty and the imposed

expectations from society.

To delve

too deep would do a disservice to the plot, although it

can be said that the ensemble cast excels and Monahan’s

dialogue pops. The third act problems from the original

are resolved and the film moves at a pace that does not

necessarily surpass, but builds off Scorsese’s previous

work.

Rating:

|