|

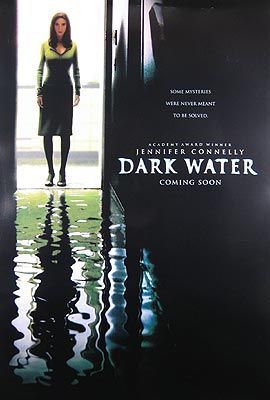

Dark

Water

There have been many adaptations of Japanese horror films

of late, and their continued success only seems to encourage

studios to continue with the trend of buying up the US distribution

rights of the original films, shelving them, and remaking

them with an “American spin” to better suit

US audiences.

Wes

Craven had been circling a remake of one of my favorite

Japanese horror films, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Kairo,

for some time now, and when it was finally canned there

were sighs of relief echoing throughout the halls of Fanboy

Planet -- though that may be unrelated.

Those

cries of joy have turned into whimpers of pain, as it appears

that the US remake is in production yet again, and filming

as we speak, under the new title Pulse with Jim

Sonzero at the helm.

Let’s

digress from this digression. Dark Water, the latest

entry into the “remake genre” originated with

Hideo Nakata, whose film Ringu kicked off the recent

trend when its US incarnation, the Gore Verbinski helmed

The Ring, broke the

box office wide open. Studio executives sat up and took

note of its success and immediately began green lighting

other Japanese horror films.

To sit

and compare this current adaptation to the original film,

Honogurai mizu no soko kara, would be futile. These

remakes always take liberty with the source material, bending

it and shaping it to better suit what will hopefully equate

to box office gold. However, it’s strangely ironic

that Dark Water originated with Hideo Nakata, because

unlike Verbinski’s stylistic adaptation of The

Ring, Walter Salles’ adaptation of Nakata’s

film seems to hold truer to the basic thematic elements

of Japanese horror than any of its predecessors.

For

that very reason, this film will polarize audiences, and

ultimately be dismissed.

It is

true that Japanese horror films have contained some of the

creepiest imagery of late, and their horror/thriller elements

have somewhat rejuvenated American horror, which was quickly

becoming stifled by relentless parody. However, creepy scenes,

believe it or not, do not make a quality horror film. There

has to be something more going on behind all of the eeriness

and bloodshed, and Salles captures this perfectly.

The

real conflict in Japanese horror films always seems to coincide

with supernatural events. These supernatural events are

no coincidence, mind you, as they are intended to be viewed

as extended metaphor, playing of the strife and complications

occurring between the characters within the film.

With

Dark Water we are introduced to Dahlia (Jennifer

Connelly), a woman whom has suffered a significant amount

of trauma throughout her childhood, namely child abandonment

in the realm of physical and mental abuse. Dahlia’s

past is directly tied to her future, as she is in the midst

of a nasty divorce with her husband, Kyle (Dougray Scott),

and caught the middle of the feud is their daughter, Ceci

(Ariel Gade). Both Dahlia and Kyle are working to establish

a joint custody scenario for Ceci, but their differences

of opinion deter this from happening at every turn.

The

interesting development here is that we know that both Dahlia

and Kyle are separating for their own individual reasons,

but whether or not each individual reason is the proverbial

“right” reason is left unknown. Like many divorces,

each party feels justified in their actions, and each party

feels wronged by the other party. It’s only natural,

and the film reflects this development perfectly. When Kyle

accuses Dahlia of being crazy, we can see evidence of his

accusation, although we still side with her. When Kyle is

accused of being a cheater, his response seems quelled as

if there may be some truth to this, although this is never

really stated for fact.

This

blurred line keeps the focus on the present, not the past.

Well, for the audience at least. Dahlia’s fixation

with her past continually pulls her further and further

into darkness. On the exterior, she appears to be losing

grip of reality and behaving erratically, both signs pointing

to Kyle’s original assessment.

Dahlia’s

decision to put her daughter first in her life is admirable,

as we have all taken experiences from our past and sworn

to “right these wrongs” with our own actions

through adulthood. Relocating to Roosevelt Island, Dahlia

is able to find an affordable apartment that suits both

her and Ceci in the barest of necessities, and at the same

time serves as convenience, as it is only two blocks away

from one of the best schools in Ceci’s age bracket.

Connelly

plays wounded like a pro, and no one would doubt her convictions

here. As elements of the supernatural begin to manifest,

we are presented with reasoning for their dismissal that

not only suits the environments, but also refrains from

insulting viewers’ intelligence. The haunting of Dahlia

and Ceci’s apartment will feel reminiscent of other

films in this genre, which will likely turn many away from

the film initially. Yet it’s the manner in which these

aspects reflect the larger canvas that makes the film work

so well.

Rating:

|