|

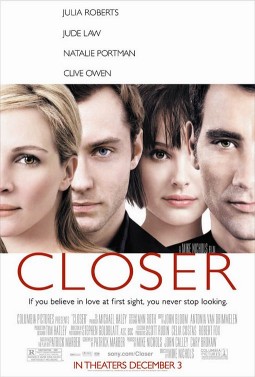

Closer

Mike

Nichols’ adaptation of Patrick Marber’s play

is definitely worth looking into. Unfortunately, it may

get overlooked.

Look

no further than the cast to see the potential in this tangled

tale of a love quadrangle between four very humanly flawed

characters. Not having seen the play to gauge a comparison

of the film to, Marber’s characters at the very least

feel like they’ve been thoroughly fleshed out.

Here

is a film that is sure to make some waves based on performances

alone. Anna (Julia Roberts), a divorcee photographer living

in London, falls hopelessly for the troublesome Daniel (Jude

Law), a former journalist turned novelist who is bound romantically

to his muse Alice (Natalie Portman), an ex-stripper turned

waitress.

How

does Dr. Larry (Clive Owen) fit in? Daniel inadvertently

introduces him to Anna after a witty yet deceitful game

of cyber-sex that is not only fresh and original, but also

more realistic than most chat room sequences in other films.

That

seems to be the heart and soul of Closer to begin

with: realistic, original, and strikingly captivating. No

two characters are completely innocent, and no character

is innately pegged with the badge of evil.

We find

ourselves rooting for each one in specific circumstances

and pitying them in others. To say that scenes this raw

have never graced the silver screen would be naive, but

to ignore their courageousness would be a mistake.

Roberts,

especially, extends herself against the typecast that usually

accompanies her name. Her Anna is capable of shameful wrong

and falls into the trappings we all find ourselves falling

into at times. She is weak. She is a coward. The same could

be said for the others as well. They are each victims of

their own loneliness and cowardice.

Larry’s

isolation leads him to troll for sex on the Internet, ultimately

resulting in his involvement with Anna. Alice, although

remarkably independent in many regards, also proves to be

running from something in her life, although exactly what

that may be is not entirely known.

Dan’s

reluctance to accept what he wants for fear of losing what

he has proves critical. He declares the desire for truth

from Alice, yet he refused to be truthful with her about

his feelings for Anna. Anna feared the consequences of the

truth with Larry, yet was brutally honest with Dan. Dan

declares that “lies are the great currency of the

world” when asking why Anna didn’t simply lie

to protect him from her dalliances.

In retrospect,

Larry’s pride drives Anna away, but his regret feels

genuine even if he is a prick at times. Alice wants to love

unconditionally, but her lack of trust stems from some dark

secret in her past. She holds all the cards in the game

of lies, as Dan learns ultimately in the end.

Much

has been made of the question of nudity in relation to Portman’s

depiction of Alice, a character who leaves a life of stripping

behind her when she moves to London from New York only to

find herself returning to this practice in a time of weakness.

The

gossip columns had a field day with Nichols’ decision

to excise sequences of full-frontal nudity at Ms. Portman’s

request. Despite the hullabaloo, Closer manages

to survive without these scenes.

In fact,

Portman manages to pull off yet another brilliant performance

in the wake of her stints as Princess Amidala in George

Lucas’ “galaxy far, far away,” first in

Garden State and now here as Alice.

Every

aspect of this film is tangible and genuine, yet some may

find it difficult to relate to some of these characters

because of their flaws. The problem is, these flaws are

what make them each indelibly human and ultimately drives

this film forward.

This

isn’t your run of the mill perfunctory romance, a

tale of lovers who overcome the odds created for them specifically

to overcome. Instead, there is no clear-cut couple that

stands out in the film because they are all guilty in some

ways. We

believe the love between these characters, and as they get

pulled further and further into the tangled web of lies,

deceit, loss, and love, we can’t help but identify

with the places they find themselves at times.

When

Dan and Anna decide to break it off with Alice and Larry

respectively, owning up to their year-long affair, we peek

into situations everyone finds themselves in at times in

our lives, playing the roles of the heartbreaker and the

heartbroken. We see evidence for and against each couple

when they are together, and when one pair emerges “triumphant”

in the end it doesn’t necessarily come across in a

welcomed fashion but we accept it.

We understand

the motivations, and we aren’t asked to agree, but

we are forced to consent to the result much like we must

understand and respect the choices of friends and loved

ones in our lives.

Although

Closer may not be regarded as Nichols’ strongest

work, he still deserves kudos for adapting this stage play

to the screen in such a way that the essence is retained

throughout. At times one can picture these scenes unfolding

on a stage, yet without feeling overtly staged.

Rating:

|