|

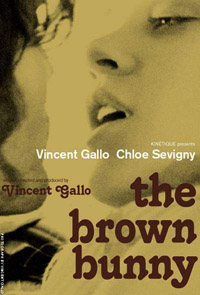

The

Brown Bunny

The word “controversy” has pretty much gone

hand-in-hand with Vincent Gallo’s latest film, The

Brown Bunny, since its Cannes screening left its audience

in a shell-shocked state.

Much

has already been made of the reported boos, the critical

backlash, a press-fueled tiff and eventual reconciliation

between Gallo and film critic Roger Ebert, and the fact

that the film features a hardcore oral sex sequence in its

third act. It almost seems redundant to mention them, but

how does one ignore them?

At the

end of the day all that really matters is how the film holds

up on its own. In this case what we get is a profoundly

personal and deeply affecting film that engages its viewers

by referencing those moments of reflection, remorse, and

perseverance that we’ve all individually experienced.

The

plot centers on Bud Clay (Gallo), a motorcycle racer who

appears self-sufficient at the racetrack. We watch as Bud

competes in a race on his brown number 77 Honda in a very

sullen and withdrawn sequence shot entirely from a fan’s

perspective atop the bleacher seating, and after the race

he alone loads his equipment into his van and then departs

for California.

From

this opening sequence it becomes apparent that is a “man

without.” He is a man without a pit crew, and as the

film progresses it continues to reveal more and more ways

in which he is in isolation.

From

this point on, the film takes a slow approach to Bud’s

journey, and this is where it loses a lot of its audience

in the process. In likely homage to Monte Hellman’s

1971 cult film, Two-Lane Blacktop, the film is

about the journey, and about placing its viewers in that

van with Bud as it crawls from state to state.

Two-Lane

Blacktop focuses on the essence of travel and life

on the road as it details two very silent types, James Taylor

stars as the driver and Dennis Wilson is his mechanic, as

they move from one drag race in search of the next. In Bunny,

we watch as Bud travels from female encounter to female

encounter, all the while attempting to piece together his

past and why he behaves the way he does with the women he

meets on the road.

He at

first appears to be seeking out his next female relationship

when he approaches these women, but something is preventing

him from following through on these chance encounters. With

each new one we learn a little bit more about Bud and we

get a better view of what it is that is haunting him.

At one

point early on in the film, Bud visits an elderly couple,

parents to Daisy, the woman Bud loves. We learn from this

encounter that Daisy has not called her parents in some

time, and that Bud and Daisy have a house together in Los

Angeles. When asked if they’ve had kids yet, a note

of solemnity tinged with loss is evoked, implying that Daisy

may be the key to Bud’s behavior.

Clocking

in at a runtime of only 92 minutes, the film feels much

longer due to its somber pacing. To some, this could be

a bit trying, and others may argue that this is intentional

and therefore essential. I happen to agree with the latter.

The

film’s subtlety works on a tremendous level, offering

slight implications as clues and symbols throughout the

film. Gallo’s use of doorways in contrast to historical

conflict is significant, and a revelation surrounding Bud’s

roadside encounters is so subtle that when it becomes apparent

one nearly slaps himself for not noticing this connection

initially.

Fortunately

film as a medium is completely subjective, so everyone will

take something different from a film such as this. When

Bud reaches Los Angeles, he eventually encounters Daisy,

his lost love.

Their

encounter is one of rigid unease, a wealth of emotions buried

behind an attempt by Bud to remain stoic and unmoved while

Daisy pleads for his forgiveness. To reveal much more would

damage the essence of the film itself.

However,

the graphic nature of their final encounter is entirely

appropriate within the context of the film and the development

of Bud’s character. This is not an attempt at titillation

or cheap sensationalism.

The

fact that the “blow-job scene” has been so widely

publicized is a detriment to the film, and will likely lead

to countless eager adolescents seeking out a glimpse at

a hardcore scene involving Chloe Sevigny. What they will

be met with instead is an artful film about introspection

and soul searching, and this will likely cause frustration.

Even

Gallo himself calls attention to this on the film’s

posters and ads by including “Adults Only” on

nearly every poster. Of course, although the film includes

an “adults only” sequence, Gallo seems to be

requesting that only those willing to screen this film in

an adult manner be admitted.

Gallo’s

reputation also works against him here. The film opens with

a title card listing Gallo as the Writer, Editor, Producer,

and Director of the film. A quick cruise of the IMDB credit

listing for the film and you will see that he also stakes

claim over nearly every other aspect of the film as well.

This

is not meant to imply negativity towards Gallo in any way

whatsoever. This film is extremely personal and it’s

easy to understand why he would take such measures of control

over these aspects of the film. However, one can see where

many might interpret his ownership over the film as being

an act of pompous ego.

That

Gallo stars in the film and his character is the recipient

of the controversial sex act only adds fuel to the argument

that this film is nothing more than an exercise in self-indulgence.

In that regard, there is only one guarantee with The

Brown Bunny, and that is that the film is sure to polarize

audiences.

Those

willing to look past all of the controversy will find a

deeply engaging film that is ascetically resonant and rooted

in humanity from a filmmaker willing to go out on a limb

at all costs. In at least one opinion, it’s well worth

the journey.

Rating:

|