|

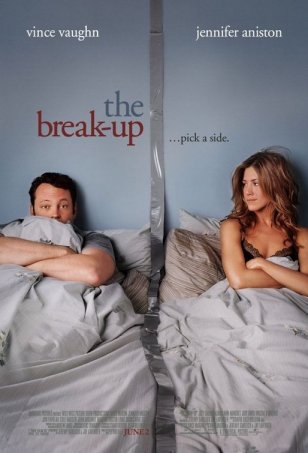

The

Break-up

Break-ups are always tough and this one is no different.

This isn’t to say that the film is terrible by any

stretch of the imagination. Peyton Reed’s work here

is true and honest, almost to a fault. The depths of which

this story plumbs are a little too real for some to really

sit through without squirming at times.

Again,

this isn’t to say the film is bad. It’s actually

quite good, as uncomfortable as it may be at times. You

see, not to call upon stereotypes or anything, but based

on this fanboy’s experience it’s pretty safe

to say that we’ve all found ourselves in Gary Grabowski’s

(Vince Vaughn) shoes at one point or another.

Well,

those of us who’ve had girlfriends, that is.

Sure,

it’s a low blow, but it’s funny. It’s

this sort of mixture that the script by Jay Lavendar and

Jeremy Garelick blends to uneasy perfection. Is it funny?

Sure, but the reality always keeps the gags grounded, keeping

them from veering off too deep into any sort of situational

comedic riffs the Frat-Pack has become so synonymous with.

The

premise is fairly simple. The trailer would have you believe

that the plot centers around Gary’s separation from

Brooke Meyers (Jennifer Aniston), a rough decision to part

ways that leads to a game of one-upmanship in an effort

to keep their beloved apartment. It does, sort of, but what

really takes front and center is the elements of the actual

break-up, the bad decisions each one makes that helps perpetuate

the split, and the stubborn pride that leaves them to an

uneasy crossroads in the final act.

Yes,

the film actually sticks to its guns and delivers on the

promise of its title. Gary and Brooke split up, realize

their emotions rushed them into the predicament, and then

attempt to win one another back in a passive aggressive

bout of tit for tat.

What

makes the pill tougher to swallow is Reed’s attention

to the details. Either Reed, or his spectacular second unit,

places a large amount of emphasis in the minor fringe details

that make these splits so much more difficult to stomach.

The

opening sequence features some of the best secondary photo

work ever used in a romantic comedy of this ilk. The photos

depict Brooke and Gary in various circumstances that look

like anyone else’s collection of photos: bar night

with friends, Halloween parties, vacations, photos taken

of unsuspecting partners, candids with funny faces, and

rounds of board games with the gang.

The

photos are so realistic that they look as though the cast

spent their time being these characters during the downtime

on the set, and someone simply snapped photos of them doing

so.

Nothing

in the world can be more uncomfortable than a tiff that

erupts during a dinner party with friends or family, and

Reed begins our journey with this very concept. In arguments

it is often true that both parties, to some degree, are

at fault in some fashion. That said, and excepting that

Brooke is accountable to some extent, Gary is a grade-A

jerkoff.

He’s

the typical man we all hope, deep down, that we are not

really like. He ignores Brooke’s dedication, the load

she carries, and the fact that she pulls this ship along

more often than he picks up a PS2 controller.

Reed

places scenes in sequences that help his viewers along,

depicting first Gary’s day job, performing as a bus

tour guide for tourists in Chicago. We then cut to Brooke,

the manager of an art gallery for an eccentric and self-absorbed

artist named Marilyn Dean (Judy Davis).

Marilyn

and Gary have something in common in that they both place

their needs and wants before Brooke's. However, in time

we learn that Marilyn is capable of recognizing the error

of her ways, and instead of playing out her part in a typical

“bitch boss” secondary fashion, Davis brings

a level of redemption to Marilyn that Vaughn’s Gary

is merely incapable of.

We then

cut to Brooke at home, preparing a dinner party for their

respective families. Gary returns home from work with the

incorrect number of lemons needed for a centerpiece, and

proceeds to ignore Brooke’s pleas for help while citing

“down time” as an out. This escalates into the

fight that splits the couple up, but what is interesting

is how Gary is unable to see past the little details of

the fight, while Brooke is incapable of expressing to Gary

why these little things add up into a greater, more meaningful,

feeling of being taken for granted.

|

Because

Reed’s work so effectively eviscerates the dynamics

of relationships on the brink, the marketing campaign boasting

a lighthearted romp of a split actually acts as a disservice

to the film. As stated before, the film has its moments,

most notably the interactions between Gary and his best

friend Johnny O (Jon Favreau), who seems to not only serve

as the sidekick, but the person who puts things into perspective

even when the light at the end of the tunnel has faded.

In the

end, no amount of laughs will elevate this film from what

it is, a deft look at the inner workings of failed communication,

to the comedy it purports itself to be.

Rating:

|