|

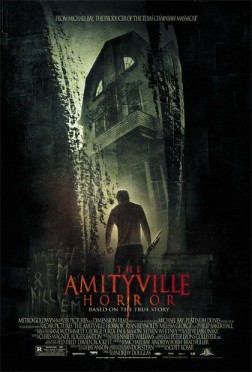

The

Amityville Horror

remake (re•make): To make again or anew.

This

seems to be standard protocol for most Hollywood studios

these days, and on paper it makes sense. Dollars and cents.

Hell, if sold before you might as well try to cash in on

the property again, and it sure beats coming up with anything

original, right?

Well,

let’s be fair. Nothing is new or original in the studio

system anymore. With the term “original” applied

to various films which basically pay homage to countless

genre films from the past, it’s become quite clear

that true “originality” comes in the approach

of presenting the material, no matter how tired it may be.

Consider

Dawn of the Dead. The George A. Romero original

offered just the right amount of gore to appease horror

fans while finding something substantial to say about consumer

culture in a socio-political fashion. When news of a remake

circulated it sounded like yet another tawdry cash cow in

the works.

Then

it hit. Dawn of the Dead

was remade anew in 2004 at the hands of relatively unknown

director Zack Snyder, and surprise, surprise, it worked.

Albeit nowhere near touching ground trail blazed by the

original, Snyder and screenwriter James Gunn kept only the

essentials (zombies, survivors, and a mall) and made the

rest their own. All of this aside, the remake was as resounding

as its predecessor, but was still distinct enough to hold

its own.

So along

comes relative newcomer Andrew Douglas’ remake of

The Amityville Horror, and the result is a remake

that actually surpasses the original in some regards, despite

a few trappings that manage to fall flat. Along with screenwriters

Scott Kosar and Sandor Stern, Douglas approaches the remake

in less of a revisionist method, yet still manages to fix

a few complications from the original film.

One major

overhaul, and the weightiest gripe about the film, is the

bow to hyper-stylized flash cutting that is all the rage with

younger directors. Nothing establishes a creepy surreal tone

like longer, more uncomfortable takes, and a film like this

should be more about tone and unease than shock-schlock cutting

for effect.

The

opening sequence, detailing true-life murders of the DeFeo

family at the hands of their eldest son, is such an assault

to the senses that it is difficult to tell which offends

more, the act we are supposed to be horrified by or the

barrage of images and sound effects used to accentuate each

cut made.

Once

one wades through the muck, the film settles in, slowing

the breakneck pace from the initial onslaught in favor of

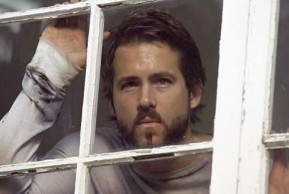

character development. George Lutz’s (Ryan Reynolds)

arc, especially, benefits from this decision in comparison

to the original film.

George,

portrayed deftly although surprisingly by Reynolds, is established

here as a widow’s new husband who desperately wants

to do the right thing in regards to his wife, Kathy’s

(Melissa George) children. George’s plight is portrayed

in such a way that prior to the move into the house, viewers

admire his efforts with young Billy (Jesse James), who adamantly

wants to hate him for stepping into the family.

George

never presses to replace the memory of Kathy’s ex,

and the pain on his face while trying to engage Billy despite

being cut down is very real and resonant, which is a big

surprise from Mr. Van Wilder. We see the strains on the

family before they even step foot in Amityville, and these

are the same strains that the spirits in the house exploit

during their twenty-eight day stay.

The

Lutz’s are informed of the DeFeo murders, and being

skeptics of the supernatural opt to move into the house

regardless. Financial woes play into this decision, considering

they could not afford such a house under any other circumstances.

As George becomes more and more detached from the family,

monetary pressure masks his shift in behavior. Karen seems

to equate George’s mood swings as product of the stresses

of making this venture work, not something as outlandish

as hearing voices in the late night hours.

|

She

remains unaware of the late night murmurs pushing George

to the edge, and his lack of communication in this regard

doesn’t help. Take away the “spooky ghost and

ancient burial ground” logic, and beneath is a situation

that commonly troubles younger married couples: lack of

communication pulls apart relationships. This serves as

a metaphor for the deterioration of the American Family

in a similar fashion that The Exorcist riffed on

the effects of a divorce on mother-daughter relationships.

This

leads us to one of the major flaws in the original, lack

of character development coupled with some illogical plot

points. In the original, George is never established as

a caring figure, so when he begins acting irrational, we

know he is likely under the influence of the house, but

we aren’t given anything to compare his harsh punishments

to.

Also,

the process of discovery should lead to logical decision

making within the confines of character. Karen’s research

into the house’s history leads to finding after finding

that would have prompted any normal family to reconsider

their stay before anything truly disturbing had even transpired.

The remake slows this progression, and Karen doesn’t

really begin clueing into what could be at stake until it

is too late which builds to a more cathartic and emotionally

logic third act setup.

Overall,

the film maintains the look and feel of the seventies without

stooping to self-reflexive inferences. Even the film stock

is grainy, recalling the gritty cinematic aesthetic of horror

films from that era. Now if only these directors could learn

that with precision framing, attention to mood, and establishment

of tone, the need for rapid fire splicing is rendered unnecessary.

Rating:

|