Comics Unmasked: Art and Anarchy in the U.K.

James Bacon is a train Driver working in London but originally from Dublin. He also loves comics, theatre, history and books, runs conventions, writes about these activities and has edited a Hugo-winning Fanzine with our own Reverend Dr. Christopher J. Garcia. James Bacon is a train Driver working in London but originally from Dublin. He also loves comics, theatre, history and books, runs conventions, writes about these activities and has edited a Hugo-winning Fanzine with our own Reverend Dr. Christopher J. Garcia.

So after posting this piece on the Forbidden Planet blog in the U.K., he gave us permission to reprint his report on this British Museum exhibition here on Fanboy Planet.

Thank you, James! This is incredible stuff!

Described as a ‘Pivotal Exhibition’ where the British Library wants to have a show ‘that gives creators the respect that’s due to them’, this is indeed a brilliantly conceived and realised exhibition that will be accessible to all while remaining especially satisfying for long-time comic readers.

As one walks into what is the largest UK exhibition of comics ever, one realises that this has been a vocational vision to show the thousands who walk in this summer that comics are much more than two-dimensional children’s ephemera.

As you look through a quirky comic frame-like portal that leads you into the exhibition, there is an incredible piece of graphic installation art – Dave McKean doing what he does so skilfully – creating an image for the viewer that demonstrates the dynamics that are comics.

As curator Paul Gravett talks about all the help that he and the team have had, I am transfixed.

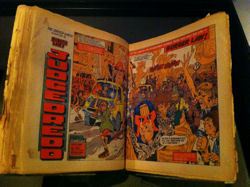

"Indicative not exhaustive," I hear as I walk down steps surrounded by brilliant colour into a selection of cases displaying all types of treasures. The British Library has a massive collection of comics which include some unusual rarities, fanzines and small runs that one would never know about.

"Five batcaves below and a fortress of solitude in Boston..." holding vast amounts of comics, claims Gravett.

Along with Paul Gravett are co-curator John Harris Dunning, Adrian Edwards and Roger Walshe of the British Library. Walshe repeatedly says that he is not apologising for what is on display; this is a strong exhibition that some might find alarming, controversial, but the message here is that comics are not just for kids, and the exhibition is about the message of the media of comics, not any particular genre.

Yes, comics are fun, they are a pastime, they are beautiful, they are fantasy, they are powerful, they are a true form of literature, imparting dangerous thoughts and ideas, asking questions of the reader, forcing reflection and consideration, or making laughter. Yes, comics are fun, they are a pastime, they are beautiful, they are fantasy, they are powerful, they are a true form of literature, imparting dangerous thoughts and ideas, asking questions of the reader, forcing reflection and consideration, or making laughter.

As one walks into the exhibition, it is clear each section has its own message to tell, and there certainly there has been considerable thought put into the displays and exhibits.

Mischief and Misbehaviour is an initial theme, but where does that end? At what stage does it become violent?

The clever placement of a Mr Punch next to a Punch comic for children (unknown) from 1921 side by side with the Gaiman and McKean Punch from 1994 neatly shows a lineage.

A section on children’s comics not suitable for children displays an Action Comic from 1976, a youth seemingly attacking a policeman (actually it wasn’t, but with a police helmet on the ground nearby it fueled 1970s censorship calls from the self appointed ‘moral majority’), while a pamphlet from the Communist Party in1954 looking to restrict and portray comics as harmful reflects the anti-Americanism agenda of the 1950s.

In 1954 the National Union of Teachers held an exhibition of horror comics, demonstrating the harmfulness of them, although Gravett pointed out that when it went on tour around schools as a warning, it perhaps proved more of an interest than deterrent.

It seems quite innocuous until one realises that this scaremongering against comics led to the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act 1955 in the Houses of Parliament. These folk-panics and media scare mongering have direct effects in terms of legislation and censorship, they can and do impinge on our democratic rights to self expression and freedom to read or view what we wish.

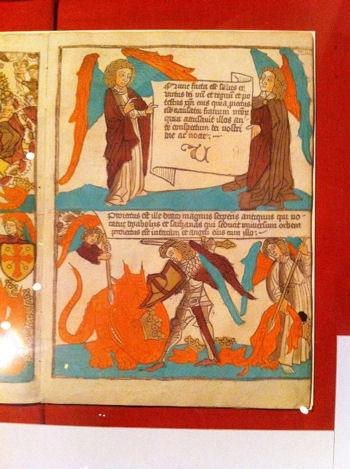

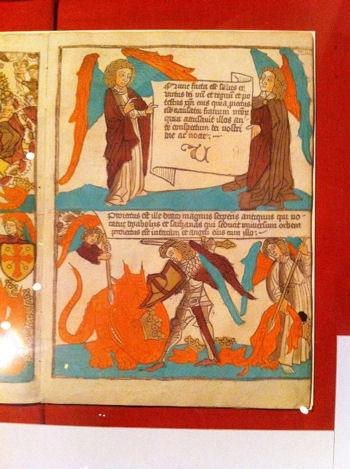

Preaching To The Converted displays a rather interesting item from the Library’s collection, a 15th century Bible printing, a block book from the 1470s that has all the trappings of a comic. Preaching To The Converted displays a rather interesting item from the Library’s collection, a 15th century Bible printing, a block book from the 1470s that has all the trappings of a comic.

Edwards asks "Isn’t this a comic?" and continues, "colourful, with panels, speech balloons, angels killing dragons..."

The same cabinet holds examples of Preacher and True Faith while the Green Lantern story, "Tygers", written by Alan Moore and showing an alien being crucified, caused some upset at the time.

The American Comics Code Authority subsequently told the artist – Kevin O’Neil – that his rendition so horrified them that anything further by him would not be approved .

It will surprise none of our readers, I think, to learn that this was seen as a badge of honour by O’Neil, and the fairly purposeless CCA was finally dissolved in 2011. No tears were shed.

Comics are a powerful way to tell a story, and a whole section, some six wall cabinets, display examples of creators using the comic form to tell personal stories that take one through all the highs and lows of a personal nature, from child loss to social status to diversity and more.

This area is a delightful and colourful blue and every cabinet has something new to me, or something I pleasantly recognise, be it Posy Simonds’ Tamara Drew or Third World War by Pat Mills.

At various stages, mannequins are gathered, garbed in urban clothing, masked with V for Vendetta masks. A large group stands silently as one walks into the black walled section on politics.

Background recordings are playing and the sounds of Margaret Thatcher, unrest, steel-heeled footsteps, a police siren in the distance, all add an atmosphere to this section, indicating how comics have always been a source for the voicing of discontent.

The Glasgow Looking Glass, a Victorian satirical comic paper which is considered the first dedicated comic that was produced, is on display, its growing popularity required a later name change to The Northern Looking Glass.

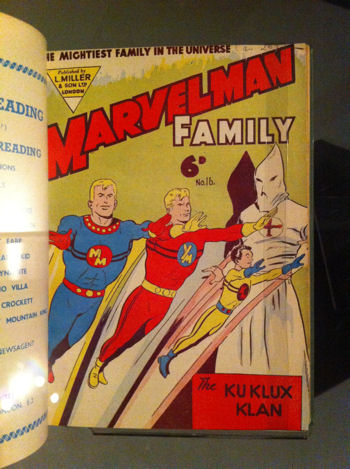

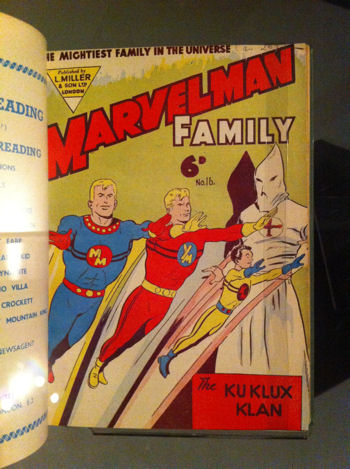

The juxtaposition of comics is intelligently done as a National Front comic – telling white youth what their rights are from 1981 – is placed next to Marvelman fighting the Ku Klux Klan. The juxtaposition of comics is intelligently done as a National Front comic – telling white youth what their rights are from 1981 – is placed next to Marvelman fighting the Ku Klux Klan.

Then the Anti Nazi League, portraying two friends - one black, one white - joining forces to fight as heroes against ‘the lie squad’, demonic KKK-dressed Nazis who are distributing obnoxious propaganda and burning down a black community youth club.

It is quite raw stuff.

The rights and wrongs of society are explored by comics, and so they are on display too.

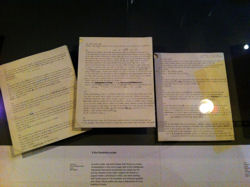

V for Vendetta, of course, is a seminal work in this genre of the comics medium, and there is an original page and a selection of the script on display.

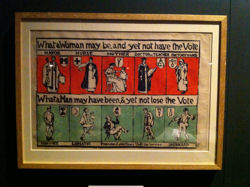

The rights of those marginalised or abused or mistreated is a focus, and women’s rights, gay rights, and campaigning against big business all feature in comics.

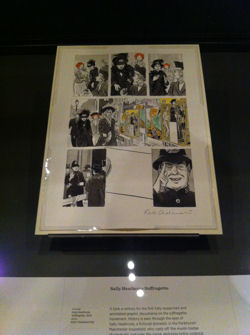

It was lovely to see an original Suffragette comic next to the just-published Sally Heathcote Suffragette graphic novel by Mary Talbot, Bryan Talbot and Kate Charlesworth.

Then the atmosphere changes again, as drapes and red paint and lights conjure a more seductive feeling, as one is led into the section on erotica and comics of a sexual nature. A display from the libraries archives showing what erotica was circulating before comics took on the mantle, identifies the nature of humanity’s interest in sex, and then there are comics of all types, from erotica to titillation to mischievous vulgarity.

Of interest was a piece by comedian and television impresario Bob Monkhouse from 1949 in Oh Boy!, which I had not expected.

The serious also permeates the whimsical in a pornographic misappropriation, as "Rupert Finds Gipsy Granny" and gets up to naughtiness – a teenage idea realised by 15-year-old Viv Berger which led to the longest obscenity case in UK law.

Who would have thought that a mash up of Robert Crumb and Alfred Bestall could cause so much upset, but it really did with the editors of Oz 28. Jim Anderson, Felix Dennis and Richard Neville were up in the Old Bailey for conspiring to “corrupt the morals of young children and other young persons” by producing an “obscene article” found guilty – and initially sentenced to a custodial sentence.

Again, smart choices by the curators.

One is soon confronted by Lawless Nellie, the character created by Jamie Hewlett specifically for this exhibition, and a section on Heroes and Superheroes is presented. One is soon confronted by Lawless Nellie, the character created by Jamie Hewlett specifically for this exhibition, and a section on Heroes and Superheroes is presented.

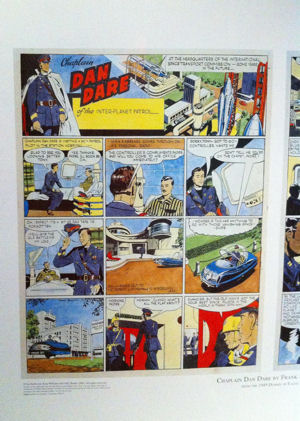

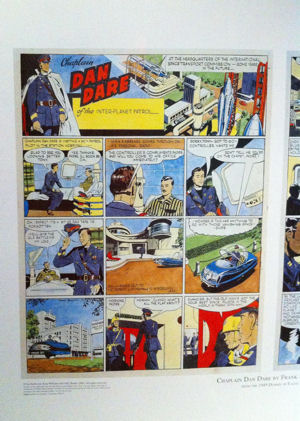

Eagle, a comic started by vicar Rev. Marcus Morris, which published Frank Hampson’s creation Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future, is an interesting alternative to the US horror comics of the same time.

Dan Dare was seen a morally sound response to US comics and initially was going to be a chaplain before becoming the RAF ‘Spitfire pilot in space’ type we revere today as one of British comics’ greatest heroes.

The original chaplain Dan Dare story hangs on the wall of a beautifully created space, an interior of a home, with shelving containing comics and all sorts of gems. An audio recording of a 1950s Radio Luxemburg Dan Dare radio play is one of many recordings available to listen to.

It is interesting in this section to note that the British Library focuses on indigenous creators, and highlights how subjects and boundaries which may be too risqué for the more conservative in the comics industry have continually been pushed by the British comic contingent.

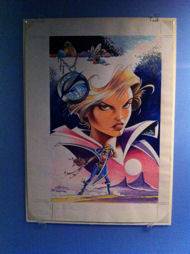

Edwards was keen to point out that it is noticeable how many British comic heroes are women, from Modestly Blaise to Tank Girl to Halo Jones, all with a particular edge to them.

The curators have purposely placed items together, making the viewer naturally ask questions, so the image of Springheeled Jack next to Batman can only but make one wonder, question where did the idea of Batman come from. Is there a connection or coincidence?

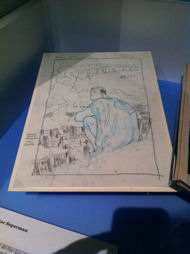

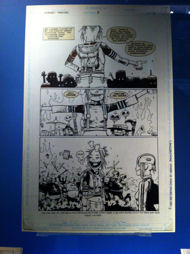

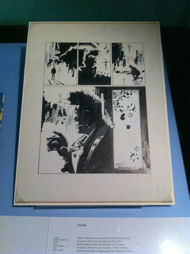

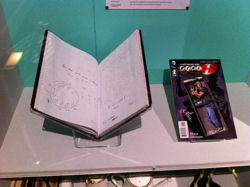

In this section I was thoroughly impressed by the selection of original artwork; a Frank Quitely Batman pencil is near an All Star Superman cover, a Dave McKean Joker mask, page 16 of the first issue of Watchmen, notes for Kick-Ass and acclaimed novelist China Mieville’s notebook for his recent comics foray, Dial H For Hero.

As a fan this is the type of rare item that really catches my imagination, as one can see into the process, guess at what notes or thumbnails mean, and glance beyond the pages of a comic.

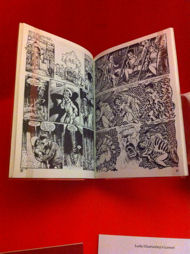

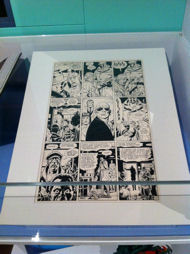

The original art continues apace with Slaine, Halo Jones, Tank Girl and Zenith, while notes and thumbnails for Arkham Asylum, an original Sandman script and a thumbnail version of the comic all allow an insight into the workmanship of the creators, the collaboration, the involvement and detail.

A slew of events are planned over the next number of months at the Library (although a couple of items have already sold out), including talks by Warren Ellis, Grant Morrison, Dave McKean, Melinda Gebbie, Dave Gibbons, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Mike Carey, Posy Simmons and Bryan Lee O’Malley are all on offer. This will culminate in a COMICA festival weekend.

This is a fantastic exhibition, and there are many more sections with so many items on display, so much to mention, but suffice to say it is fabulously good value and is wonderfully satisfying. It truly shows comics in a very respectful and enlightening way.

;

|