| Graphic

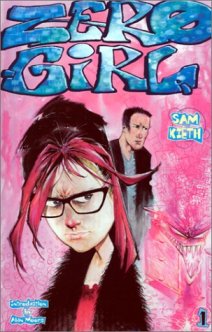

Depictions: Sam Kieth's Zero Girl

A couple

of weeks ago, reader Robert Sparling wrote to us pointing

out a gap in our coverage: graphic novels and trade collections

that the average joe stumbling into a comics shop might miss.

Damn. He was right. But did we have time to add that to the

editorial load?

Thankfully,

Robert stepped up to fill that very void. And this is his

first piece. Let us know how you like it.

When I

picked up the graphic novel Zero Girl, written and

penciled by Sam Kieth, I had no idea what I was buying.

For those

unaware, Sam Kieth wrote the critically acclaimed series The

Maxx, a book that gained mainstream success despite being

labeled as anything but. I'll admit, I never read it and I

saw only a few episodes of the short-lived MTV animated series

based on it, but I'd gleaned from interviews and articles

concerning Sam Kieth that he is no writer (or artist for that

matter) to be overlooked.

After

picking up Zero Girl, in short order, I had my mind blown.

It's

the story of a loner/outsider named Amy Smootster, and her

unique propensity for soaking her feet whenever she is embarrassed

(her feet are literally soaked with water through an unexplained

quirk of Amy's body). Amy is sixteen and understandably, not

enjoying high school, suffering as a target of ridicule for

her peers. Shocking as it is, Kieth actually chooses to make

Amy's tormentors female bullies, physically violent toward

her, where most writers would make them catty girls who set

out to ruin Amy's self-esteem or cause some other psychological

damage. In hopes of turning guidance counselor Tim's attention

away from the "weird girl," the bullies assure him that Amy

is a "goth" and a "slut."

Tim sets

out to help Amy, whom he considers to be "troubled" after

he discovers that she lives alone and spends a lot of time

hiding and sleeping around campus. When he finally gets to

speak with her, she dismisses him as attempting to "save (her)."

He also

discovers that Amy sees the world in shapes; circles are safe

and friendly and squares are dangerous. Amy seems to have

some strange power over circles. They can protect her from

harm (in one instance, saving Tim and herself from a cascade

of falling bricks by shielding them with a circular cut-out

piece of newspaper). As we get farther into the comic, we

discover that the "squares" may be trying to kill Tim and

Amy, and only the "circles" can save them.

But all

this is background for the real story, the most unsettling

and painfully well-written aspect of the comic: the budding

romance between Amy and Tim. Kieth takes an incredibly taboo

subject (one which he is personally familiar with, as he admits

in his afterword) and treats it with the weight and respect

it deserves.

Amy is

actually far more mature then her sixteen years, perhaps even

more so than the elder Tim, and actively questions him on

why the idea is so impossible for them to be together. Reading

these exchanges between Amy and Tim, which border on flagrant

flirting sometimes and outright fights in others, the reader

is made to feel the discomfort of the situation. How can Tim

deny that he is feeling a connection to Amy? How can Amy convince

him that it's okay for them to be together? Would it be right

if they were together?

The reader

has to ask these questions and it's almost impossible to answer

them. The issue is too fractured, too conditional, to be fleshed

out in any certain way, and Kieth drags the reader through

the muck of his moral questioning. You may feel dirty reading

this comic, but it's a good, intelligent kind of dirty.

As the

plot progresses, Amy and Tim's relationship (if one exists

at all) is discovered and brought into question. At the same

time, the "squares" begin manifesting in one of Amy's bullies,

turning her into quite the little psychotic with an extreme

dislike for circles and Amy. In the end, it comes down to

Amy and whether she can survive a "square" assault alone,

and finally discover whether she and Tim can be together.

The art

on this comic is expert, perhaps the most dynamic art recently

done in comic books or graphic novels. Kieth's artwork, it

would seem, never repeats a pencil line. Every time we see

Amy or Tim, they are rendered slightly different. Sometimes

the art is very humanistic and gritty. People are drawn proportionately

and with great detail. At other times, Kieth opts for a different

approach, making them seem cartoonish and exaggerated.

Zero

Girl also requires a graphic format. The artwork flows

so well with the words, you could not separate the two and

get the same story. When Tim is being questioned about his

involvement with Amy, the reader can clearly see that Tim

has started to see the world the way Amy does: in shapes.

The policemen questioning him begin to change shape, one's

head stretching to triangular proportions while the other's

head elongates into a cylinder. It's downplayed and not mentioned

in text, but it's a fantastic visual device.

Kieth

also has no qualms about suddenly switching mediums. Several

panels appear to be pencil and ink, and suddenly the book

breaks into a pastel-colored pencil motif to depict one scene

or another. Even watercolor gets some space.

Buy it.

Read it. It's a very affordable $14.95 at your local comic

shop or bookseller and well worth the moral debate that will

inevitably ensue inside your head. I recommend Zero Girl to

comic book aficionados, English professors, art students,

and anyone who just plain likes a good read with an added

bonus of visual storytelling.

Currently

30% off at Amazon -- Zero

Girl

|