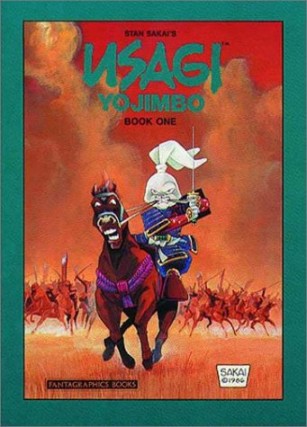

| Usagi

Yojimbo

I was a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles freak

back in my pre-adolescent days. I had every toy imaginable:

from that electronic plastic disc (“pizza”)

shooting thing, to the Michelangelo surf board, not to mention

all the action figures a grubby handed kid could get for

Christmas. I even had the Ninja Turtles table hockey game.

We all have skeletons in our closets.

The

reason I bring this up, is because it was on Teenage

Mutant Ninja Turtles where I was first introduced to

Stan Sakai’s character of Usagi Yojimbo, an anthropomorphic

samurai rabbit that for one reason or another, was fighting

the Turtles and then became friends. (My memory is slightly

fuzzy on the actual plot specifics of the episode; such

disgrace to the fanboys I am.) It wasn’t until years

later that I discovered that Usagi was actually a character

from the comic book world, and had been since the mid-1980s.

There

was something an explosion of black and white comics in

the 1980s; some claim Eastman and Laird’s Teenage

Mutant Ninja Turtles comic, which would explain Usagi’s

arrival on the cartoon, started it. This gave Stan Sakai,

a letterer on Sergio Aragones’ Groo the Wanderer

at the time, a chance to be noticed by Fantagraphics Books,

who began shoving work at Stan in the form of Usagi Yojimbo

requests, eventually leading to an ongoing series.

Usagi

Yojimbo has survived the lull in popularity of black

and white comics in the early ‘90s, and the varying

tastes of comic readers that is a benchmark of the current

readership, by moving publishers several times, most notably

to Dark Horse, and the publishing rights for Usagi material

is split between Fantagraphics and Dark Horse, Fantagraphics

handling the first seven books, and Dark Horse covering

everything else, which is hefty since the number of collections

of Usagi is near twenty volumes.

The

first volume, which is a loosely strung together series

of events culled from the short stories of our hairy retainer

that appeared in Albedo Anthropomorphic and Critters,

shows Usagi as a samurai without a master, having lost his

lord in battle with the Lord Hikiji. Miyamoto Usagi is now

a ronin, taking work as a yojimbo (“bodyguard”)

whenever he can. The reader follows Usagi through several

short stories, wherein the presence of Lord Hikiji’s

machinations towards the Shogun seem to foreshadow an active

future for Usagi, and the fighting prowess of our katana-wielding

hero is but to the test more than once.

What

marks this series as interesting is the way Sakai balances

the humor, the violence, and the action so well. Most cartoon

comics that came out of the 1980s weren’t all-ages.

Many simply used the conventions of cartooning to juxtapose

against the usually violent or overtly sexual nature of

the story. Eastman and Laird started Turtles as

a parody of Frank Miller's Ronin with a slight

dose of X-Men, and it was never meant to appeal

to the preschooler audience that the TV show captured so

well (until Laird and Eastman decided to completely throw

out all the things that made their comic popular, in favor

of dumbing it down for the kiddies and making a mint doing

so…smart or morally bankrupt is left up to you fair

reader).

Usagi

isn’t necessarily meant for children, but it

could easily be read by children with no ill effect. The

subject matter is simply good story telling with nothing

to mark it as either “children’s” or “adult”

reading. Sakai easily shifts the character from the role

of dangerous samurai to coincidental punching bag as Usagi

gets mistaken for a horse thief, caught up in assassination

attempts, and even befriending convicted killers while traveling.

And more importantly, Sakai gives his character a sense

of humor that is subtle and matches the feel of the feel

of a typical “swords and samurai” book, but

marks it as clearly American. Manga will often overplay

the role of the samurai, taking the practice of bushido

to the extremes and bogging down a good plot with too much

pomp and ceremony involving the samurai code, which usually

makes for characters that are one-dimensional. Sakai makes

Usagi personable, funny, angry, wistful, and a dozen other

characteristics, because Sakai wants the reader to be able

to relate to the character, and because he wants the flexibility

as a writer to have fun with his own creation.

All

of this may be helped by the fact that Usagi is a big honking

rabbit with a sword, but floppy ears aside, Usagi never

feels out of place in his anthropomorphic status to the

reader. Usagi as a character is about as organic as the

carrots you would put in his food bowl, were you to possess

such an awesome pet.

Sakai’s

artwork, along with Kyle Baker and Jeff Smith’s, is

what gives me hope that American cartooning has yet to die

a horrible death at the hands of the anime revolution. I

like standard comic book art that is meant to reflect more

the anatomical qualities of it’s characters, but there

are times when a thousand sinew marks and face lines on

a comic character becomes too much (Liefeld, this means

you). I sometimes thirst for the simplicity of less cluttered

artwork.

This

is not to say that cartooning is somehow “simple”

in that it isn’t complex, but that cartoon characters

can sometimes emote better, can move in more definite ways,

than their human counterparts with far less work on the

reader’s part in reading. If Usagi is angry, the eyes

bulge and the eyebrows arch; when he’s happy he smiles

a wide grin. Sakai is able to describe pictorially the movement

of his characters in a definite manner.

One

sequence in which Usagi moves from one end of the panel

to the other to remove the head of an assassin about to

kill a child, is wonderful because of the way that Sakai

illustrates it: Usagi drawn in greater degrees of detail

as he moves from the left to the right of the panel, demonstrating

the speed of Usagi’s sword, as well as Sakai’s

great sense of linear timing. Also of note is the fact that,

even in the tale of a samurai, Sakai shows little in way

of gore and blood (the number of blood sprays could be counted

on one hand, and a shop teacher’s hand at that), keeping

the violence clean but still interesting.

Usagi

Yojimbo Book One is a great comic that doesn’t

appear deliberately “all-ages,” but simply manages

it through the strength of its creator’s artistic

ability. It’s well-worth $15.95 for the first volume,

and the subsequent volumes more than likely live up to the

first. In an age chalk full of bad “cartoon books”

being published in the US merely because they’re origins

lie in the land of the rising sun, it’s good to see

an American comic that puts most of them to shame using

their own conventions. Well done, Stan Sakai.

The Ronin (Usagi Yojimbo, Book 1)

|