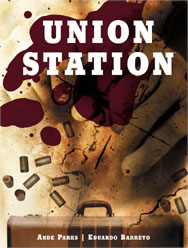

| Union

Station

Why is

it that so many crime comics are set sometime in or around

the 1920s and ‘30s? I mean, Judd Winick’s Caper

had its maxi-series’ beginnings in the earlier part

of the 20th century; The Road to Perdition and subsequent

tie-ins from Max Allan Collins were Depression-Era; and Torso

from Bendis (all hail the man who writes half of Marvel’s

comics) was in the time of Elliot Ness, albeit being based

on true events he had little choice in the matter.

Maybe it’s an American obsession with

the time of cops and robbers; a time when buttonmen were

seen as often as a Starbuck’s and the only way you

knew a cop wasn’t dirty was if he was dead. For some

reason we love to tell our seedy stories near the time of

the Capones and Derringers, maybe to make the crime seem

more gentlemanly as we remember a world were gangsters sold

liquor instead of cocaine and if someone got plugged, they

probably did deserve it. I couldn’t say for sure.

But

yet again the 1930s appears in a comic about the illicit

doings of the underworld, this time in Union Station

from Oni Press.

It’s 1933 and Frank Nash is a criminal

with a past that has finally caught up with him. After being

nabbed by the Feds for some small time crime, Nash is due

to be transferred to Kansas City to start his incarceration,

but when his train gets to Union Station, a botched attempt

to free him leads to a massacre that affects the lives of

three men: FBI Agent Reed Veterlli, reporter Charles Thompson,

and underworld gun-for-hire Verne Miller.

Veterlli has to try and find a way to cope

with his mistakes made during the massacre while trying

to keep his morals intact. Verne Miller is on the run after

trying to help a friend and is closely pursued by Hoover’s

best, and Charles Thompson may find that trying to find

out what really happened at Union Station may cost him and

his family dearly.

This

is Ande Parks’ first foray into writing, having been

an inker of some renown on Green Arrow, and while

it’s clear that he has the ability to tell a story,

he needs more polish before he writes a really good one.

It’s clear that Parks has a love for the material,

being a native of Kansas and having obviously delved into

a decent amount of research on the actual Union Station

Massacre.

However,

he gets bogged down in what I can only assume is historical

detail, forgetting to really flesh out his characters in

favor of assuming the reader has some familiarity with who

these people are. The only character that he spends much

time developing is Charles Thompson, and to Parks’

credit, I found myself thoroughly interested in Thompson.

Small touches like Thompson’s easy relationship with

his son, and his utter willingness to dote on his wife when

she is still reeling from a double mastectomy (information

that Parks wisely and subtly allows the reader to discover

through the artwork and not blatant dialogue), show him

to be warm and compassionate. In several scenes, when his

family is threatened we can see the panic and fear in the

character, not just in facial expression, but in action

as well. Thompson is also the only character that gets flashbacks

to the carnage at Union Station, as well as a dream sequence

that has little to with the story, but helps to define his

relationship with his family a little better. If the comic

had focused on Thompson, it might have been a better read

as we followed only his investigation into the events of

that day.

But Parks gums up the works with the three-character

split that occurs. Vetterli and Miller are neither well

defined nor interesting enough to keep a plot thread tight.

Parks never establishes Vetterli as a very moral man early

on, other than simply mentioning that he’s Mormon,

so his moral agonizing over his survival later in the book

just sounds like whining and rings false. When Vetterli

gets pigeon-holed into knowingly accusing the wrong man

for the events of that day, his acceptance of the situation

isn’t really shocking because the character never

really went anywhere, never got down to any soul-searching

so to speak, so the reader could really give two shakes

what he does.

Verne Miller is even worse: he’s just

a thug with a gun that owed Nash a favor, and the reader

really doesn’t know what that favor is. Parks gives

him little if any characterization, so little that Parks

didn’t even deem Miller’s demise page-worthy,

as in one panel he is escaping the cops, and a few pages

later, he simply ends up dead in a photograph. The almost

pointless (and historically fuzzy) addition of Miller’s

girlfriend into the mix serves no real purpose because we

don’t even see their relationship as humanizing. He

almost seems to treat her with contempt for some reason,

not to mention they only appear together in one scene.

The artwork is good. Eduardo Barreto has

a talent for drawing the 1930s, and his very technique screams

“old school.” He shades his inks using small

dots and crosshatching that are very reminiscent of the

way comics used to be colored; the old three-color-dots

technique, and his abundant use of shadow and straight line

shading create an incredible feeling of 1930s ambience.

His characters are distinct, but only until they all don

the typical fedora and trench coat cliché, and then

it becomes extremely hard to tell what’s going on.

This was a bad, but probably historically accurate, artistic

choice. The actual massacre scene is atrociously hard to

follow, as everyone is dressed the same, and one gaping

head wound looks just like any other. This would be the

only argument for coloring this book, as some color might

help the reader differentiate between cop and crook.

Nothing

outside of Thompson’s storyline really captures the

attention, and start-to-finish, nothing much happens in

the book. There’s a massacre. There’s some feds.

There’s…not much else.

|