| Graphic

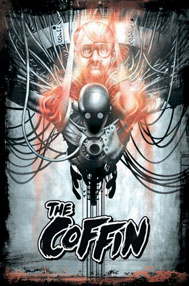

Depictions: The Coffin

Robert

returns this week with another look at a book you probably

missed, but for the record, Hollywood hasn't. Plans are afoot

for a film version of The Coffin, and once you read Robert's

review, you'll understand why.

Is there

an afterlife? Does the human soul exist? Do our bastards go

to Hell and our saints to Heaven? Thanks to Oni Press, we

now have the answers to these questions in the form of The

Coffin, written by Phil Hester and drawn by Mike Huddleston.

This

graphic novel is the tale of Ashar Ahmad: genius scientist,

apparent atheist, and cold-blooded jerk. Along with his assistant

Liv (who just happens to be the mother of his young daughter

Billie, a familial responsibility he chooses to ignore), Ahmad

has designed and created an impermeable, strong membrane that

he claims can trap a soul after the death of the human body.

Along with a CPU attached to the membrane's shell that sends

electrical impulses along the membrane causing it to constrict

and retract, these suits, or "coffins," can simulate human

movement. Effectively, Ahmad has created a way to become immortal.

Now enters the scary-bad-guy.

The man

who has been providing Ahmad with his generous funding is

Oliver Heller, C.E.O. of HellerTech, and the world's oldest

man at one hundred and forty years old. How did he get this

old, you ask? Why yes, it is the most disgusting way

possible: he kills people and takes their organs, then has

them transplanted into his body.

Heller

has been looking for a way to cheat death and may have found

it in Ahmad's research. Fearing Ahmad would take the research

and sell it to someone else, Heller sends two of his most

loyal employees (and by "loyal" I mean "sociopathic") to kill

Ahmad and Liv and steal the research.

They

succeed, putting two bullets in Ahmad and leaving him for

dead while they set explosives and finish off Liv. While the

two employees escape, Ahmad drags himself to a vat of his

soul-trapping polymer, where a prototype coffin waits for

him. He dives in and it all goes black.

Now come

the theological upheavals. Ahmad expected to die and see nothing.

Imagine his surprise when he finds himself in a Dante-like

version of Hell, complete with tortured souls and probably

the most interesting rendition of Satan to ever appear in

comic books. The Devil (who is never actually saddled with

a name or moniker; neither is "Hell" for that matter) takes

Ahmad on a small tour of the inferno, all the while assuring

Ahmad that it doesn't matter what he believed in: Hell is

the reality.

But Ahmad

isn't dead yet, as his former lover/assistant Liv tells him

when she appears to him in this afterlife. He has a chance

to go back and do it better, to live a better life than before.

"Come on, didn't you ever read A Christmas Carol?" she asks.

And he goes back.

Ahmad

emerges from the tank, clad in his polymer "coffin," physically

dead, spiritually burdened, and wanting nothing more than

to find his daughter. But when Heller discovers that Ahmad

is alive and needed to accurately reproduce the soul-stopping

polymer, Ahmad becomes a target, and so does Billie. Ahmad

has to get his daughter back and stop Heller, and through

all this, maybe find his path to redemption.

The theological

questions Hester raise in this book are ones that have plagued

the modern cynic for a long time. We can call ourselves "atheist"

and "agnostic" and claim to have no great fear of the afterlife,

because to us there isn't one, but there is still that lingering

question of "What if…"

Ahmad

is the prime example of a character that has the belief-structure-rug

pulled out from under him. A scientist, a man of thought and

reason, he couldn't be expected to waste time being "good,"

and worrying about some intangible higher power when there

was work to be done. But then he dies and finds that all his

reason and rational analysis of the world means nothing.

We are

all pieces on a chessboard, pawns to be moved by divine powers,

of which we have little understanding and never truly will

understand, perhaps, until our own deaths. Hester perpetuates

this theme of fate and divine power throughout the book by

making Ahmad question if what he saw in his "near-death experience"

was an oxygen-deprived hallucination or actual divine warning,

though he does give Ahmad the choice to determine his own

fate at one juncture in the book, perhaps proving that spiritual

freedom still exists, even in the face of destiny.

But besides

all this theology, Hester writes a fantastic horror story.

Parts of this book are utterly disturbing in their grotesque

depictions and startling twists. Almost all the characters

are immoral in some capacity, save the daughter and one other,

and they all act the part. To kill, in this book, is common,

and one scene will teach everyone who reads it a new word:

"pithing." You may have nightmares about this word.

The images

of Hell Hester creates with Huddleston are frightening, picturing

writhing skeletons, crucifixions, and a stark white background

that makes Hell appear infinitely large. Huddleston is perfect

for this dark story. His pencils and inking are expertly done

and very detailed. He plays with shadows and negative space

better than most modern-day inkers, creating a macabre, almost

cinematic look for the book that adds volumes of sub-meaning

to every panel.

This

book is exceptionally good, though it flew under the radar

of many comic book readers due to it being in black and white.

That and Oni Press doesn't get a lot of shelf space compared

to DC or Marvel comics. They missed a great read then, but

they now have to option of reading the trade-paperback edition,

priced affordably at $11.95. So, pick this book up, take it

to the man with the register, and exchange little, green pieces

of paper for it. And then give the change to a charity or

something. You never know when some good karma will save your

soul from eternal damnation.

Or

order it on-line, providing for some Fanboy Karma: The

Coffin

|