| The

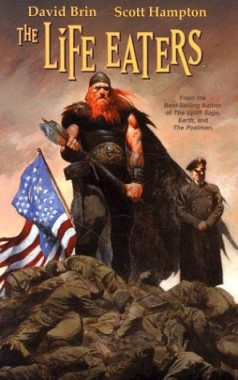

Life Eaters

Mythology

and comics go together like Ben & Jerry. It can be argued

that mythological characters were the first “superheroes”

in the sense that they were stories of men and women who

were somehow above humanity, somehow special in their abilities

to fly or hurl lightning bolts or wrestle dragons and giant

wolves to the ground.

Indeed,

comics are no strangers to the idea of anthropomorphic deities

walking the pages of their stories. Thor made his debut

at Marvel Comics way back in Journey Into Mystery,

which later became The Mighty Thor, turning the

character into one of Marvel’s most beloved

demi-gods/superhero. Hercules and Gilgamesh were also characters

for Marvel, and DC has mined the entire Roman and Greek

pantheons for stories concerning characters like Wonder

Woman and Captain Marvel. Superheroes are our generation’s

myths.

But

the gods of comics are rarely truly god-like. In the myths

of the Norse and Germanic tribes, Thor was a hard bitten

warrior god who loved battle above all, and was more powerful

than any army before him. For the purposes of story and

drama, the role of “god” in comics has been

watered down: the Thor of the Avengers can just as easily

be beaten by some random villain of the week as hamstringed

by political red tape. He is not, in essence a “god”

anymore, simply a superheroic representation of one, despite

his many mythological connections within the text. It seems

to have become the formula of comics to make gods more human,

and less all-powerful.

Which

perhaps makes The Life Eaters, adapted by renowned

science fiction writer David Brin (The Postman, Earth)

from his own short story, all the more surprising. I say

this because Brin brings with him a different kind of story

involving gods, which is more about humanity and its strength

than power of deific proportions.

During

the twilight of World War II, just when it seems that the

Nazi menace would finally be put down, the gods of Norse

legend begin appearing on the battlefield, on the side flying

the swastika. The tide of the war quickly changes and the

world grows darker as Nazi troops led by the likes of Thor

and Odin begin taking control of the world. These gods are

strong, powerful, and able to kill thousands with the throw

of a hammer.

A generation

has passed since the Aesir returned; the few people that

remain free and able to act try again and again to find

a way of killing gods, hoping to rid the world of its new

caretakers, and stop the mass human sacrifice these gods

demand. Two men will find a way to turn the tide back in

favor of humanity. Chris Turing will show humanity the way

to spit defiantly in the face of a god, while a young boy

named Lars will usher humanity back into a human age.

Brin’s

take on godhood is refreshing, and his reason for the appearance

of the Aesir makes a fair amount of sense when the Nazi

obsession with mystical artifacts and its association with

the Thule society are taken into account. Brin even points

this out in his afterword to the story. Another refreshing

bit is the way the gods are used as antagonists in every

respect. These “gods” are not human and Brin

never tries to characterize them as such. Instead, he focuses

on the human characters, namely Chris and Lars.

The

story unfolds generationally, told in the past tense by

Lars at some points, and it covers a span of years from

the 1940s to the 1970s, including major conflicts like WWII

as well as Viet Nam. I was surprised at the depth Brin was

able to reach in the much shorter form of comic books, not

only in his interesting take on the alternate history his

characters create, but with the main theme of the piece:

the power of humanity.

To explain

fully would be to give away too many plot points, but Brin

makes a fine case for showing the human spirit as an indelible

force in The Life Eaters. Both Chris and Lars,

acting as our narrators, slowly come to realizations about

the nature of the gods that appear in our world, as well

as what actually powers and creates them. All of that leads

to a great and rather uplifting conclusion about what humankind

is capable of, while still grounding the reader in the harsher

realities of Brin’s world. It’s as much a story

as it is a morality play about the abuses and rejection

of power, and it makes for fine reading.

The

artwork is, for lack of a less cheesy term, “godly.”

The last comic I read that included Scott Hampton’s

lushly detailed water colors, was Lucifer, and

I have sorely missed the man. He employs much more color

and shadow effects in this work than his short Lucifer

stint, making some scenes hum with muted energy and others

take on noirish feel (one scene of Chris Turing in a submarine,

with everything lit and shadowed in black and red, comes

to mind). His character design is good and sometimes simplified:

both Chris and Lars bear striking Teutonic resemblances

to each other, but this seems a specific choice to link

the characters through story and art. The deity designs

are appropriately sparse, marking the few Norse we see as

all similar looking (big damn Vikings with big damn weapons),

possessed of beards and scowls, with only a few details

to set them apart, which makes quasi-historical sense considering

variation in fashion is hard to pull off when your options

are chain mail and fur. Hampton’s panels all flow

well, and he sets up some very good visuals: everything

from splash pages of massive battles, to two page spreads

of deities facing off, to pull back perspective shots, Hampton

knows his art and makes it good.

Wildstorm/DC

are offering this original graphic novel for $19.95, which

is a little pricey, but it is a high-end graphic story,

not to mention it’s knocked down from the original

hardcover’s price. Plus, the small afterword by Brin

is interesting, as well is the artwork demonstration Hampton

chucked in the back of the book, so dropping $20 on this

comic is well worth the loss of Andrew Jackson’s face.

The

Life Eaters

|