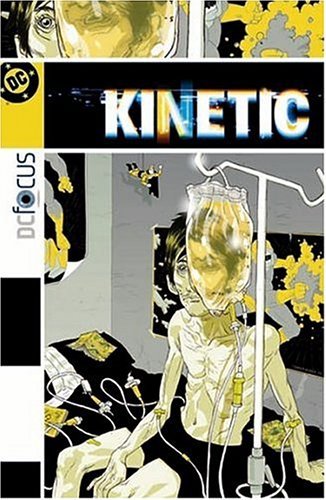

| Kinetic

The really

great comics leave us with something after we’ve finished

them. Sometimes it’s something as simple as a line

of dialogue that echoes inside our heads for hours, trying

desperately to explain itself to the reader.

Sometimes

it’s something more, or possibly worse; I remember

after I’d read V for

Vendetta for the first time, it was something like

1:00am. I kept staring up at the ceiling of my bedroom,

not really thinking about anything but thinking. I wasn’t

geeking out over what a great comic I’d read or how

wonderful Moore was as a writer, but I was remembering something

that was in the introduction Moore wrote to the graphic

novel, when he was talking about the British then recently

(in the 1980s) passing Clause 28, which called for homosexuals

to be rounded up and placed in concentration camps to stem

the tide of AIDS. He said something to the effect of “England’s

not a nice place anymore. I don’t think I want to

live here.”

This

is bad paraphrasing on my part, but that line kept flying

through my head as I replayed every panel of that comic

book. It’s been years since that night, and I’ve

re-read V since then with no ill-effect, but what

I remember most after reading it for the first time is that

I was afraid. Not of a totalitarian regime of English Thatcherites

or a knife toting, bomb-happy vigilante; I think I was scared

of the comic itself. I think I was scared that within two

slim pieces of cardboard resided a story that was powerful,

frightening, and horrible, that showed every facet of the

human condition from the soul-gutting depths of despair

to the freedom and dignity inherent in the human spirit.

Yeah it was a story, with characters interacting and all

the regular stuff, but underneath the plot and the themes

and the dialogue was something frightening.

The

best I can do to describe it might be to say that it’s

the same as when you’re standing on the edge of a

cliff looking down. Your feet are stable and safe and you

know this, but when you look over that edge, suddenly you’re

not fine and you’re not stable and your heart is beating

faster than it should. Your knees get weaker and you have

to step back, only you can’t step back after you’ve

read something. You just stare it right in the face and

hope it goes away.

I’ve

never felt this with another comic until now, some time

this afternoon when I read Kinetic. The story the

creators tell is a story that captures humanity in ways

rarely seen in a book about people with superpowers. It

gives a brutal and honest account of the teenage condition

and demonstrates the utterly insane thoughts that can entrench

themselves within our minds at that age. And it shows us

that those thoughts never really leave us.

The

book was created by Allan Heinberg (The O.C., Young

Avengers) and Kelley Puckett (Batgirl), penned

by Puckett himself with artwork from Warren Pleece. It is

the story of Tom Murrell, a boy stricken by diseases of

every kind, sickly and infirmed since early childhood. His

only friend is his mother, a woman so obsessed with keeping

her son alive that life itself has lost any other meaning,

yet a woman that both hates and loves her son for the burden

he represents. Tom hates his life to the point of considering

death as the better deal. Then Tom discovers that he has

powers.

Here

is where we should see the emergence of the classic troubled-teen-gets-powers

scenario, wherein the teen gets powers, does some good,

becomes a hero, etc. We do not actually see that. Instead

the narrative takes a turn for the original in that nothing

happens. Tom’s weakness, his insular life, is not

escapable. Even with a body powerful enough to crush boulders,

he is still a prisoner in his own mind, monologing his every

thought and action inside his own head. He has fantasies

about using the powers he has, but never actually acts on

them. He has dark thoughts that seem horrific, but Puckett

subtly reminds the reader that these thoughts are the same

ones we all have: violent urges, thoughts of using force

to get what we want, etc.

And

because these thoughts are self-contained within the mind

of the main character, we see them as he does, with no outside

moral framework. The reader is forced to judge Tom by his

own standard of moral behavior, which is extremely intriguing,

forcing us to both be disgusted by and feel empathy for

him.

The

artwork by Pleece is excellent, owing a lot to the choice

in coloring done by Wendy Broome and Brian Haberlin; the

entire comic is colored in only varying shades of red and

blue, with black inking and gray shading. Pleece’s

style is highly reminiscent of Daniel Clowes' work on comics

like Eightball and Ghost World, with a

style stressing facial expression and realism.

Moreover,

Pleece’s style of pacing is nothing short of excellent;

he is willing to go from a full page panel to cramming sixteen

panels to a page, and because he has a slow revealing style

that establishes each panel, it never feels disjointed or

wrong. The story flows easily, making it a literal page

turner, as well as functioning parallel to the high and

low points of Puckett’s script. Combined with the

contrasting color structure, the artwork on this, while

not always the perfect aesthetic visual, is some of the

most in-depth and engrossing artwork I’ve seen in

comics.

And

here I’ve described, maybe even gushed over all the

very good technical aspects of this comic, and as I look

down on it lying on my desk, there is still a small tick

at the back of my neck. It’s scary how very much the

main character’s thoughts are transmitted to the reader.

The writer has created a story that demands you feel what

the character feels, never allowing us to step outside the

small world of Tom’s head. We really experience what

he feels, with no room for anything else.

And

I think that’s what the fear might be: that we could

get pulled in or pulled over the edge of a story and fall

into it. The good stories leave us with something. They

leave us with a clear understanding of the power one story,

one tale, one character can have over us. They show us their

influence and when we see it, we cringe a little because

we didn’t know it was so easy to take us over. Kinetic

is one of those stories, and if you can look over the

edge and not stumble, is well worth $9.99 for eight issues

of material.

Kinetic

|