While

some may object to the smaller company being absorbed by

one of the Big Two, the money behind DC is helping bring

more of the European comics to American readers, and more

European talent (the English don’t count as European;

sorry Warren Ellis). Talent like Enki Bilal.

Bilal

has been working as a comic artist and writer since the

mid-seventies, and is best known for his Nikopol

trilogy, the third volume of which (“Equator Cold”

or “Froid Equateur”) was named Book of the Year

in France, which is nothing to sneeze at considering it

is the first graphic novel to do so in France, and I can’t

think of an American comic book that has reached an equivalent

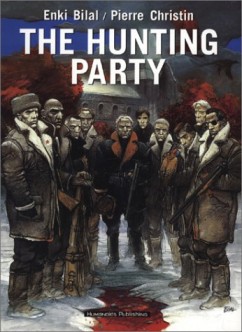

level of national prestige. So when I saw a copy of Bilal

and Pierre Christin’s The Hunting Party…well,

honestly I didn’t really have any interest in the

book, but figured it would make for some fine review material

so I grabbed a copy.

Something

happened while reading it that has rarely ever happened

to me while reading a comic book: I knew that it was a well-written,

well-researched story with excellent artwork that had several

intellectual levels to it’s plotting and structure,

and I still didn’t like it.

The

problem may arise from the subject of the story. The

Hunting Party stays true to its name as it is the story

of a hunting party during the 1980s, composed of various

leaders of the politiburo and Communist Party of the Eastern

Bloc nations. The focus of the party is Vassili Chevchenko,

a patriarch of the party whose career dates back to the

time of Lenin. The various members of the party discuss

the career of their comrade, now stricken with facial paralysis

and unable to speak, and praise his achievements while hunting

various types of game and fowl. But the hunting party is

made up of the most ruthless politicians the communist party

has ever produced, and some among them are playing a deadlier

and bloodier game of intrigue than the mere hunting of animals.

While

the above description seems to label this graphic novel

an easy “thriller,” it really is not fast paced

enough or possessed of enough tension to warrant the brand.

Instead, this is more of a political history put to pen

and ink of the various communist activities after the Bolshevik

uprising, following the different hunting party members

as they recall the roles they played within the CCCP. World

War II features heavily in the flashbacks of some members;

one recalling his internment in the Warsaw ghetto, others

recalling an assortment of events and uprisings that occurred

before the fall of the Eastern block in the late 80s. All

this political muck and mire is almost always threaded neatly

with the characters’ associations with Chevchenko,

and it’s actually Chevchenko, the only member unable

to speak, who has the most to say.

Bilal

punctuates each flashback with some well water-colored scenes

to accentuate the tone, but when he renders Chevchenko’s

thoughts in image, when others are describing the events,

we come to understand Chevchenko. He is a man ultimately

filled with regret over the many horrific things he has

done in the name of the politburo, chief among them is the

death of Vera Tretiakova, a woman long dead that haunts

even his waking memory. Bilal uses two colors exclusively

to represent the thoughts of Chevchenko: red often appearing

in place of water and/or scattered around an otherwise innocuous

landscape, creating a chilling feeling that a blood covered

veranda will engender. He also uses yellow often, sometimes

to simply highlight a character or a character’s actions,

differentiating it from the rest of the panel, but sometimes

doing something else that suggests “yellow”

has a deeper meaning that eludes me.

Either

way, the wordless story that Bilal tells with images of

Chevchenko’s mind is excellently done, and helps to

pull the reader more into the political story that, at times,

appears too dense to navigate.

Christin’s

text is well researched, and his characters are all fleshed

out well enough, but the lack of danger, of tension, keeps

the reading slow, and while I enjoy a meticulously written

text under normal circumstances, the sheer density of some

of the historical and political content is such that I felt

like I was one Soviet History degree shy of being able to

fully understand the piece. It must be said that he does

create characters that are somewhat accessible to the reader,

mostly in the form of the young French translator pulled

into this den of bastards through circumstance, as we see

him react to the stories they all tell.

While

I consider all the political elements rather boring, I have

to admit to them being intricately researched: how often

will we see the Prague Spring brought up in the same comic

as the Trotsky problem? If only the party assassination

plot had been treated a bit more ominously, it would have

seemed more horrifying and less mundane than it came off

on the page. It’s well written, just in need of some

better pacing.