| Ex

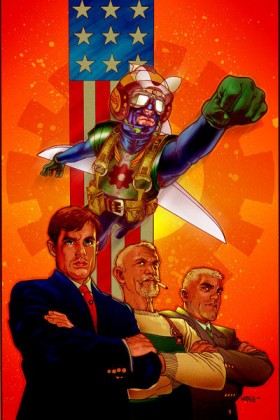

Machina: The First Hundred Days

I really

hate politics. I don’t mean that I hate one particular

party or politician, or that I find myself leaning toward

one political ideology in particular. I mean that I hate

the whole freaking system. Elections, NGOs, lobbyist, Senate,

the House of Representatives: it all just irks me.

And

it’s not just the American government; I’m as

equally annoyed with every type of governing body known

to man, mostly because I think all government runs on the

principle that people will somehow manage to not find new

and interesting ways to circumvent any system they find

themselves in and summarily screw over their neighbor. In

fact, the best system of government I’ve ever heard

of was one I believe the Vikings used, wherein the two disputing

parties would go out in the middle of a bridge, and the

last man left standing on the bridge won the argument. Sweet

wonderful simplicity.

My utter

dislike of government makes liking books like Ex Machina

somewhat difficult, as there is a ridiculous amount of bias

that I have to overcome to be objective. Thankfully, the

effort put forth by Brian K. Vaughan and Tony Harris made

it almost easy to love their story of the new New York City

mayor dealing with crisis after crisis, as well as his former

career as the world’s first superhero.

Mitchell

Hundred was just a civil engineer when he was exposed to

some type of glowing mechanism that gave him control over

complex mechanisms and machines. Soon after, he donned a

menagerie of gadgets and armor to become the world’s

first superhero, The Great Machine, but found quickly that

all he did was maintain the status quo. So, he unmasked,

ran for Mayor of NYC, and won by a landslide. And that’s

where our story starts.

Vaughan

takes a storytelling style like that found in NBC’s

The West Wing, showing us the man in power, as

well as some specific scenes involving key members of his

staff, but by using the mayoral setting, is allowed more

leeway in crafting more interesting plots. Whereas The

West Wing is far too often bogged down in more political

jargon and far-too-current events, Ex Machina balances

well the duties of the mayor’s office with the action

subplot and the back-story involving The Great Machine,

and finds a way to make the unveiling of some controversial

artwork at the Brooklyn Museum of Art just as intriguing

as a murder spree in a blizzard. I’m also fond of

Vaughan’s characterization of Mitchell Hundred and

the supporting cast of his staff. Well-defined personalities

are the norm here, almost to the point where I can tell

which character is speaking from dialogue alone.

What’s

most interesting about Vaughan’s story here is that

it is oddly light as far as intense moroseness and drama,

but still manages to be horribly sinister. The reader is

clearly meant to follow the story arc as it ebbs and flows

and shifts focus from one of the three subplots, but Vaughan

injects several brief plot points that highlight what could

be a serious underpinning plot thread of tragedy for the

protagonist. Much of Hundred’s past as the Great Machine

is unknown to the reader, and while it seems obvious his

superheroic career was short-lived, there were several places

in his past where the character feels haunted by mistakes.

References to the World Trade Center and a murderer named

Jack Pherson crop up, as well as some strange imagery, helped

by Tony Harris’ art, involving Hundred’s mother.

His

term in office may seem bright and cheerful (as bright and

cheerful being the Mayor of NYC could be), but Vaughan seems

to be pushing this a little too hard; perhaps commenting

on the facile nature of what it takes to make it politics.

Vaughan creates a very subtle dichotomy for the reader to

observe about Mitchell Hundred: there’s the Mitchell

you know, that you read about, and the Mitchell you don’t

know, that is suggested. And the best part is that it plays

out only in minor traces and steadily throughout the comic,

while never being obvious. Intricacy of plotting, thy name

is Vaughan.

Tony

Harris, it is good to have you back. Since his departure

from Starman, I’m glad to see him working

on a regular monthly series again. His artistic style has

changed much from his Starman days and has even

become sharper since his work on JSA: The Liberty File.

This is crisp, clean artwork that is distinctive in its

emotive ability and facial variation. Harris almost personifies

the kind of artwork that I think should be the mean for

comics: just plain good, reliable at all times artwork.

Harris’s emotive style also matches well the talking-heads

nature of the book, as much of the plot involves dialogue

and little action, but when the action pops up, Harris continues

to perform well is visually relating movement and scope.

Also

of note is the coloring from J.D. Mettler. Color plays an

important part in the book, as flashbacks occur regularly

and Mettler gives understated nuance to these scenes, making

their colors a little richer and more “homey”

to invoke the idea of “past.” Mettler also works

the environment well with his color schemes, making night

and wintry conditions vibrant and textured, and adding highlights

to the plots points mentioned earlier with eerie tones of

pale green.

It’s

a great collection and highly creative in its presentation,

which is something I’m coming to expect from the more

high-profile projects coming out of Wildstorm/DC nowadays.

Well worth the $9.95 for the first five issues, as well

as a behind-the-page section where Tony Harris shows off

his creative process involving photo reference. Go and buy

and finally find a governmental candidate that is both interesting,

intelligent, and can be bought for ten bucks. If only they

were all so cheap.

Ex

Machina: The First Hundred Days

|