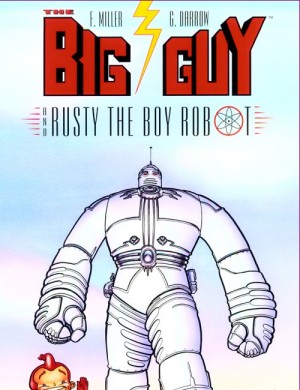

| Big

Guy and Rusty the Boy Robot

There

was a time, back before Busiek’s Conan and

the acquirement of the publishing rights to Star Wars

and many Japanese comics, when Dark Horse was a place where

you would find some of the most odd combinations of talent

and concept that ever appeared in comics. Stan Sakai’s

samurai rabbit Usagi Yojimbo and Paul Chadwick’s

classic Concrete are some fine examples of Dark

Horse’s penchant for publishing the strange and wonderful

of our comic book industry.

But

one rather obscure title from Dark Horse’s early days

have been one that I have always been on the lookout for,

and which I have finally found, is Frank Miller’s

and Geof Darrow’s Big Guy and Rusty the Boy Robot.

Japan,

after playing just a tiny bit of God, is under attack from

some malevolent force in the form of a giant lizard, but

it doesn’t have the tender disposition of Godzilla.

This beast has it in mind to destroy humanity and wipe its

stench from the planet by converting all human genetic matter

into replicates of itself. When all conventional methods

are exhausted, Japan sends in its prototype military breakthrough,

a small red headed robot named Rusty. When even Rusty fails

to cull the threat, Japan calls in its last hope: the US-made

Big Guy, a colossal metal warrior who may be the planet’s

last possible hope.

Some

may remember the brief but entertaining Big Guy and

Rusty cartoon that ran on Fox Kids a few years back,

and I’m sure even more remember the teaming of these

two artists on the super-violence pastiche of Hard Boiled,

so one might expect the comic version of these two metallic

monster fighters to be something of a middle ground between

those two works. In many ways it is; the artwork Darrow

produces here is more grotesque and far more graphic than

that of the television animators, but the dialogue, as written

by Frank “Sin City” Miller, remains

much the same as the television show designed for children.

It’s tame, subtly ironic, and only slightly mocking

of the “Giant Monster Attacks City” genre that

it tends to work both as a parody of films like Godzilla

and King Kong and as a decent adventure story.

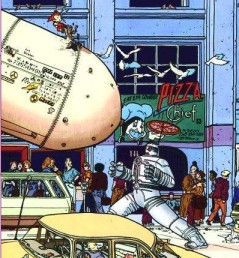

The

design by Darrow is what is the most impressive and is far

more representative of complex issues than Miller’s

somewhat simple plot and storytelling. Darrow is one of

those rare artists that can draw breathtaking full page

landscapes, as well as technical precision and facial detail,

and make all of them work in the same panel. The grotesque

nature of the monster juxtaposes nicely against the clean,

straight lines of the city of Tokyo. It highlights the struggle

that Miller is beating to death in his monster dialogue:

that of nature versus technological power.

|

Darrow's

designs for Rusty and Big Guy are also telling and representative

of more than just robots. Rusty’s design, which makes

him appear as a large-headed child with an air foil on his

head, is reminiscent Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy. This

is obviously intentional on Darrow’s part, if for

no other reason to demonstrate the difference between a

Japanese and an American design for a robot. Astro Boy

(or Tetsuo Atom for purists) was one of Tezuka’s

earliest works, and it became common after that seminal

work for robots to be depicted in manga as somewhat humanoid.

This became something of a tradition in manga, and it is

very different when compared to the American robot. The

picture of an American robot is historically drawn form

the pulp science fiction tradition, where they were odd

combinations of wires and dials and gears. Our robots, for

whatever reason, appear more mechanical than Japanese robots.

Darrow’s

design of Big Guy highlights these differences well. The

Big Guy has no mouth, square “eyes,” and is

colored white with blue metallic piping all along his chassis.

He looks like a pulp fiction robot. In drawing these characters

in this manner, Darrow seems to be trying to comment on

the differences between our two disparate societies, and

he brings up some intriguing points with his art. The Japanese,

who have made leaps and bounds ahead of the US in terms

of technological development, dream of robots designed to

appear more human. Honda’s Asimo is a fine example;

watch it kick a soccer ball or dance like a person. The

Big Guy is designed to look like a machine or maybe a suit

of armor. Darrow implies that American robots are meant

to be machines and just machines; that to make them more

human in function or appearance might weaken them.

But

one revelation that occurs later in the book leads us to

question if humanity is a negative or positive factor in

this big monster tussle. Because Rusty, the human robot,

cannot defeat the monster, but the Big Guy can stand against

it, raises all manner of questions as to what truly can

confront the onslaught of nature, in this case a giant multi-armed

lizard that can breathe fire, better.

I’m

impressed that I actually got this much deeper meaning from

a story about two robots beating the hell out of a more

talkative version of Godzilla, but Darrow’s artwork

takes the reader to several very interesting places. Unfortunately,

Miller’s writing doesn’t really live up to it.

Miller has done great things (Dark Knight Returns, Sin

City) and some awful garbage (DK2), and this

is not his worst piece. In fact, much of what he writes

is very good, especially the satirical, All-American dialogue

of the Big Guy. However, he forgot to complete the story.

|

Miller

takes the time to introduce his characters, but really gives

nothing to define them. This is not horrible, as it seems

clear to me that he is striving to lampoon some of the funnier

aspects of the “Big Monster Attacks” genre;

it even works well to eliminate Rusty, the least interesting

character early on, but problems arise here. Miller leaves

the reader with the fight to focus on, which would be fine

if he had managed to add more of an actual fight. Both narrative

boxes and the over-the-top ramblings of the monster in question,

as well as the unnecessary dialogue of those affected by

the monster’s replication process obscure the scenes

of battle.

Almost

all this extra wordiness detracts from Darrow's artwork

by covering it up, and adding very little to the story.

The amount of unnecessary exposition makes the story feel

slower. If the action is all there is to focus on, something

that is not all together bad, than the action has to take

center stage and not be made murky by superfluous verbosity.

Issues of Warren Ellis’s Global Frequency

did this expertly. Miller did not do it here.

All

in all, Miller’s lackluster writing does not help

this book, but Geof Darrow’s artwork alone is worth

the cover price of $14.95. In addition, Dark Horse publishes

this trade in an oversized format (about 9’x 12 ½

‘) so Darrow’s art is on fine display. There

is also a cover gallery from other issues, or what might

be mocked up issues, in the back along with two splash pages

of the Big Guy and Rusty battling monsters alongside the

likes of Spawn and Ash, for some reason. The story is barely

there, but enjoyable, and the art is top notch. Plus, where

else will you find a story about robots, monsters, and societal

concepts of technology? Other than on Robot Wars,

I mean.

Big Guy and Rusty the Boy Robot

|