Jim

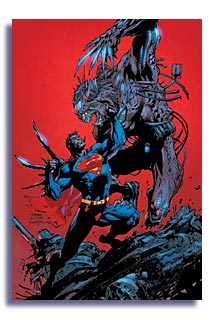

Lee delineates Superman as a near-god, perfection from every

angle. Thankfully keeping the art from too much idle idol

worship, Brian Azzarello writes even supermen as men, struggling

with their consciences and their purpose in life. 'Tis a

consummation devoutly to be wished. So why isn't this comic

book dream team putting out a more enjoyable book?

Worse,

why do I find myself actually preferring Action,

written by Chuck Austen? Kill me now.

It's

not as if Azzarello hasn't set up an intriguing premise.

In this arc, Superman battles superfoes externally and overwhelming

guilt internally for the disappearance of hundreds of thousands

of people, including Lois Lane, the previous year. He doesn't

know why it happened; he only knows that somehow, he failed

them.

And

so he turns to a priest for, if not absolution, at least

a sounding board. Like most priests in popular fiction,

this one, too, struggles over his own purity. While the

two bandy deep thoughts back and forth, Superman occasionally

gets called away to take down a monster here, or interfere

with world politics there.

Perhaps

the biggest problem lies in this being something out of

Azzarello's usual realm. He writes intrigue and crime well,

but falters with characters so archetypal. Just as Azzarello's

Batman didn't feel like Batman in his arc with Eduardo Risso,

"Broken City," this Superman seems like the character in

the story Azzarello cares about the least. For sweep, the

writer puts the Last Son of Krypton in the midst of a fictitious

Middle Eastern country's revolution, with characters that

give you the nagging feeling you've seen it all before and

can't remember if you liked it. Plus, Azzarello writes for

an artist whose forte lies in drawing beautiful people and

hideous creatures fighting, so it doesn't matter what you

think about it, anyway.

It's

not that Lee can't draw quiet moments; it's more that there

seems little point to such an exercise. He works best in

big splashy moments, because without a lot of noise you

notice how impossibly fine looking everyone is - except

of course, for the monsters.

Here,

the monster is something called Equus, a high-powered techno-workhorse

with a strong enough resemblance to Doomsday to push sales.

As a character design, Equus has little of the horse about

him, except maybe the lenses over his eyes that could stand

in for blinders. As ugly as Equus is, though, Azzarello

presents the possibility that while in service to the revolutionary

General Nox, he actually is a noble steed. But can you believe

that Superman would fly into a room full of slaughter and

be persuaded somehow not to bring the perpetrator

to some sort of justice, even if the citizenry are grateful

for the killing? (Any resemblance to current events must

be strictly coincidental. Kaff kaff.)

Azzarello

would have us believe that Superman would compromise his

own moral vision in such a situation. But then, he compromises

it every time he interferes with politics. At least when

fighting Zod, you could understand his getting involved.

Maybe

America is stuck in a grey area. In the gloom, Azzarello

certainly can spin a pretty good yarn. But somehow, no matter

how doubt-filled he may be, Superman does not belong in

that fog. He's too bright, too colorful, too important to

us as a symbol of something better. Though Austen may write

a Superman who may be a little cocky, at least that Superman

remembers who he is.

Rating: