Words

and Pictures

Writing

For The Trade

I collect

nearly a dozen monthly titles, but only buy half of them on

a monthly basis. The rest I wait to purchase in trade paperback

format. And I know I'm not alone. A rapidly growing segment

of the comic-buying public prefers putting its books on shelves

rather than sealing them in plastic just so they can be cloistered

away in the back of some dingy bedroom closet.

In an

attempt to accommodate these readers (as well as reach out

to the vast, untapped bookstore market), comic publishers

of every stripe have begun to reorient their entire business

structure from that of periodical publishing to book publishing.

In their rush to cash in on the graphic-novel goldmine, the

companies are forcing their talent to "write for the

trade" with some very negative consequences: artificially

extended storylines, first and second acts that never end,

decompressed visual storytelling… The list goes on and

on.

A typical

trade clocks in at around six issues. This is primarily for

business reasons (i.e. optimum price point and best distribution

schedule) rather than creative ones. Sometimes the trades

are split up into smaller arcs or a series of individual issues,

but just as often (especially in the Ultimate line) the story

arcs clock in it at the full six issues.

That's

a whole lot of story, the comic-book equivalent of a three-hour

movie. In order to fill up that much space, writers elongate

their first and second acts to several issues each. This not

only makes the trades drag in the middle, it also makes the

original issues all but unreadable since nothing of real consequence

happens in half of them - they're just the lead-ins to the

next issue's big revelation or climax. They're not dramatically

satisfying enough to read on their own.

I love

Geoff Johns and I love his work on Avengers, but his

Red Zone

story arc has me bored to tears. It took two whole

issues to reach the end of Act One, and even then I barely

noticed. The team has just been wandering around the red mist

for three issues while Iron Man and the Black Panther indulge

in their own subplot that moves the story forward but not

fast enough.

A writer

could craft a story with five or six acts instead of three,

but most plots simply can't handle that many reversals without

coming off as forced and artificial. Just look at Loeb and

Lee's

Batman .

Each issue

is fairly self-contained, and should stand as acts in and

of themselves, but each ends with Bruce beating the bad guy

and learning nothing. Nothing of any real consequence has

happened - except for Bruce's romance with Selina.

Which

brings me to the other way writers try to pad their scripts:

Add subplots. They use them to create numerous mini-acts within

the larger plot in order to add suspense and keep the audience

interested, but this often leads to the subplots taking over

the main plot, thus damaging the integrity of the story as

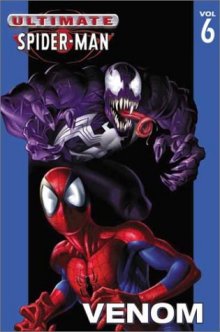

a whole. This happens all the time in

Ultimate Spider-Man (admittedly, Bendis does it

very, very well) where Peter's love life or Gwen Stacy's problems

with her dad will take up as much, if not more, page space

than whatever it is Peter is dealing with as Spider-Man.

Nor is

that Bendis' only sin. He decompresses his storytelling by

including numerous talking-head scenes that eat up pages but

manage to say a whole lot of nothing. A typical issue of

Alias

will often include at least one or two pages of the following:

Medium-close shot of Jessica Jones saying "That thing

you did was pretty impressive." That's followed by a

medium shot of Luke Cage saying "What thing, b--ch?"

Then Jessica Jones retorts with "That thing with the

super strength." "Oh, that thing," Cage replies.

"Well, what about that other damn thing…"

And it

continues on like that for pages at a time (curse words added

to make it feel more like an authentic MAX title.). Sometimes

it works on a stylistic level, but from a storytelling perspective

it just stops the story cold. The many Bendis disciples out

there have all copied this conceit. Too bad they aren't able

to pull it off half as well as he can - and I don't even like

it much when he does it.

On the

opposite end of the spectrum from the "talking-head syndrome"

is "widescreen storytelling." It all started with

The Authority

, which had good reason to use that particular

style. Plus, Ellis and co. knew how to plot solid four-issue

stories action stories. All main plot that just keeps moving

ahead relentlessly with no subplots or long soliloquies.

The problem

is that practically every title under the sun has begun aping

that style to some degree. Splash panels now seem to exist

solely for their own sake. There's no compelling dramatic

or visual reason for most of them. They're just there to look

pretty and turn 18 pages of story into 22 pages of comic.

Personally I'm not big on paying for a 22-page comic I can

read in less than five minutes.

So how

to avoid "writing for the trade" (EPIC writers and

comic execs take note!)? Don't make the story longer than

it deserves to be. If it can be told in two issues, don't

try to stretch it to three or four or six. Even one page of

fluff is too much. All that matters is that the story's good.

Once that's

taken care of, everything else falls into place.

(editor's

note: Yes, it's probably hypocritical and shameless to then

link several of Joshua's citations to Amazon, but hey, they're

out there. You might want to buy them. And Fanboy Planet needs

the support.)

|