|

Part

1, Part 2

One

For The Ages:

Barbara Gordon and the (Il)-Logic

of Comic Book Age-Dating

Part Three: Age of Iron or Age of

Rust?

Wizard

claims that "The Modern Age" did not begin

as much as default, being birthed from the orgy

of crossovers beginning with Marvel Super-Heroes'

Secret Wars where "team-ups lost their

specialness […] subsequently signaling the

end of the Bronze Age" ("One for the Ages",

2001: 91).

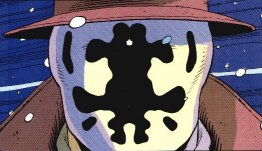

Klock

considers a "Dark Age," a bastard spawn

of Watchmen's deconstructive tendencies -

"Alan Moore was disturbed to find people actually

liking Rorschach, and wanting to read more comics

that starred characters like him" (2002: 80).

Semich agrees to this assessment, even if under

the moniker of "The Iron Age," where much

of Superman's morality, optimism, and confidence

were siphoned away (which has only in recent years,

with writers like Grant Morrison on JLA,

begun to return). Klock

considers a "Dark Age," a bastard spawn

of Watchmen's deconstructive tendencies -

"Alan Moore was disturbed to find people actually

liking Rorschach, and wanting to read more comics

that starred characters like him" (2002: 80).

Semich agrees to this assessment, even if under

the moniker of "The Iron Age," where much

of Superman's morality, optimism, and confidence

were siphoned away (which has only in recent years,

with writers like Grant Morrison on JLA,

begun to return).

Ultimately,

though, Klock rejects both of those models, instead

proposing the Third and Fourth Movement of the genre:

a system of Oedpial narratives in the tradition

of theorist Harold Bloom where one generation's

heroes supplant the former (e.g. Watchmen, Authority,

Planetary). Coogan agrees that the movement

has been a four-step one, but he holds to a different

chronology. His Baroque/Iron Age "began with

DC Comics Presents #26 (October 1980), the

first appearance of the New Teen Titans," marked

by a "larger shift toward reinvigoration"

than ever before (Coogan, 1996).

Coogan

never quite defines what he means by "reinvigoration,"

but provides examples of it: "Self-conscious

revivals sprouted everywhere: the Fantastic Four

and Superman by John Byrne; Daredevil

and Batman by Frank Miller; Thor by

Walter Simonson; Captain Marvel and Marvelman

in Miracleman and the Charlton heroes in

Watchmen, both by Alan Moore" (1996).

These

examples, though, are highly problematic. While

Watchmen originated from a Charlton character

proposal, the ultimate product had little to do

with them at all. And Miracleman was a forced

alteration of Marvelman, caused by Marvel

Comics' lawyers on the British import. Further,

it becomes difficult to distinguish how these are

greater revivals that those of the Silver Age or

Bronze Age, some of which Coogan names to concede.

Coogan posits that a Second Golden Age now follows

the rather empty Iron one, where the staid superhero

conventions are reborn and experimentation lives

again.

In

a sense, his forecasting fulfills Busiek's own:

"I haven't heard anyone put together a decent

argument for another Age after Silver […] But,

I'm sure somebody will - I'm sure there's some sort

of organizing principle out there. Whether it's

writer-driven or artist-driven, it's always a cycle"

(Lewis, 2002). Franke and Wechsler-Chaput also admit,

"There is no clearly defined Age after the

Silver Age, although a number of possibilities such

as Platinum, Bronze, Independent, and (in more depressed

moments) Mylar and Silicon (the last based both

on computer coloring and the ever expanding female

breast size in many comics these days) have been

suggested" (1998).

Bailey

follows the "mineral theme" to an extreme,

proposing "The Mica Age" and the "Electroplate

Age": "Mica" because "glitter

frequently contains little more than powdered, color

mica," referring to the cheap marketing gimmicks

of the late 90s, and "Electroplate" because

of its deeper-than-Silver penetration such as Kingdom

Come's admirable and "surprising discovery

of everything Kirbyesque" (2000). Bailey

follows the "mineral theme" to an extreme,

proposing "The Mica Age" and the "Electroplate

Age": "Mica" because "glitter

frequently contains little more than powdered, color

mica," referring to the cheap marketing gimmicks

of the late 90s, and "Electroplate" because

of its deeper-than-Silver penetration such as Kingdom

Come's admirable and "surprising discovery

of everything Kirbyesque" (2000).

To

summarize, one has a number of broad dates to use

as guidelines in moving, to use Bailey's phrase,

"toward a consistent nomenclature for the Ages

of comics" (2000). The Golden Age, with some

precursors, begins in June of 1938 with Action

Comics #1, the debut of our recognized Superman.

The Silver Age is after 1955, most likely September

1956 with Showcase #4, the debut of Barry

Allen as the revamped Flash. The next Age, which

I hesitantly call Bronze, comes as early as 1967

with Strange Adventures #205 (Deadman's first

appearance), but more likely between 1970 and 1972

for a multitude of possible reasons and events.

If there is a fourth Age, its beginning ranges from

1980 to the early 1990s, if it can even be said

to exist. The 2003 viewpoint of this article is

most likely too myopic to suggest a subsequent Age

without at least a decade of distance from which

to view it.

Systemical

Logistics for the Ages

It is now worth suggesting a particular perspective

from which to examine all of these aforementioned

theories: Consistency.

As

said in the opening, this article is more interested

in the logic behind these Age-systems than the systems

or dates themselves. And, for the most part, few

of these personal systems exhibit a consistent logic

all through their various stages; many manage to

isolate a range of years, such as the summary above

has just done, and then, within that span, seems

to find the event that holds the most impact to

them personally. In addition, there is a remarkably

strong bias towards formulating these Ages strictly

in terms of progress; the industry's backslides

and declines in are often relegated to either designations

like Bailey's "tribulations," or they

are overlooked entirely. While Bailey's "Mica

Age" may be a little extreme, it at least confronts

the declining standards of the comic book product

of that time, similar to the discarded "Dark

Age" perspective.

This

over-optimism and slapdash date-selection process

belies any application of hypothesis or scientific

method; to be useful to the academic and not just

the collector or fanboy, a degree of infused objectivity

is required.

Coogan

and Klock, regardless of their actual selections,

have the most consistent systems, with Semich a

distant third. Coogan's analysis is based on Schatz's

template, a very safe and wise procedure; while

one can dispute its application to comics as a medium,

to criticize its consistency would require deeper

familiarity with Schatz's own corpus and his work

as a whole. As it stands, Coogan remains true and

consistent to his source, straying only to extrapolate

and deduct what comes next. He looks for those moments

that best fit Schatz's mold; the only question,

then, would be whether Schatz's theory is appropriate

for this inter-media correlation.

Likewise,

Klock has his own mentor of sorts, Harold Bloom

(and, to a lesser degree, Slavoj Žižek),

and keeps his theory always front-of-mind. Any detours

into nostalgia or outside commentary are soon righted

by a return to his Oedipal paradigm. And, Klock

is further limited - said in a positive sense -

by focusing primarily on narrative rather than industry

fluctuations, social climate, or staffing changes.

Outside

of his mineral theme, Bailey holds to no steady

source of data. His examples run the gamut from

narrative-driven to industry-driven to marketing-driven.

The same holds for Wizard, Dashiell, and even Busiek

(though, given the chance to rebut, Busiek might

argue his focus to be on eras of experimentation,

which, in turn, argues against Coogan); first-appearances,

creator turn-over, price-increases, and audience-targeting

hold to no one (or two…or three) criteria.

And, only if one argues that Semich tracks shifts

in Superman's morality - an issue only made overtly

in his Iron Age section - can he be said to have

reasonable consistency. Format-driven, narrative-driven

(including both conventions and overall tone), price-driven,

staff-driven, society-driven, morality-driven, progress-driven,

aesthetically-driven, etc.: By what standard does

one judge the Ages?

This

article has an answer, but certainly not the answer.

After all, the goal is not to create a new system

to beat all other systems - the intent is not to

slug it out with any of these aforementioned writers.

But, the following system (with Barbara Gordon in

the place of Bloom or Schatz) is proposed in order

to demonstrate how a consistent criterion can help

in rationally sorting through the Ages without totally

discarding the traditional Gold, Silver, Bronze,

and even Iron classes. This

article has an answer, but certainly not the answer.

After all, the goal is not to create a new system

to beat all other systems - the intent is not to

slug it out with any of these aforementioned writers.

But, the following system (with Barbara Gordon in

the place of Bloom or Schatz) is proposed in order

to demonstrate how a consistent criterion can help

in rationally sorting through the Ages without totally

discarding the traditional Gold, Silver, Bronze,

and even Iron classes.

To

demonstrate my personal logic, return again with

Action Comics #1. Again, it is highly significant

given its opening pages "fully employs the

definition of the superhero of mission, powers,

and identity. The very first page presents the origin,

analogical science (superhero physics), the costume,

the dual-identity, and the urban setting. In the

story itself emerge the secret identity, the superhero

code, the supporting cast, the love interest, the

limited authorities, and the super/mundane split"

(Coogan, 2001, my emphasis).

A

key but overlooked piece of Action Comics

#1 is the birth of the superheroic ethic: a morality

system that demands great power be used for the

greater good. In short, this is the reason why the

term "superhero" was coined following

Superman's debut and why Action Comics #1

is elected the genre's starting point. Golden Age

stories would tend "to be straightforward confrontations

between good and evil in which the superhero, society,

and the audience were all presumed to be on the

same side and working for the same goals,"

those goals being "the defense of the normal,

with defense of property rights and relations included

therein" (Coogan, 1998: 439).

These

principles remain rather firmly in place, even as

the character who inaugurated them began to change

slightly. Coogan believes that "by the end

of 1940 nearly all traces of Superman's social conscience

have disappeared and he fights to protect property

against theft, politics against disruption, and

life against killing, thus enshrining the status

quo" (Coogan, 2001). These

principles remain rather firmly in place, even as

the character who inaugurated them began to change

slightly. Coogan believes that "by the end

of 1940 nearly all traces of Superman's social conscience

have disappeared and he fights to protect property

against theft, politics against disruption, and

life against killing, thus enshrining the status

quo" (Coogan, 2001).

Semich,

on the other hand, sees the 1940s version of Superman

as:

…essentially

a sort of "super-Roosevelt." He spent

most of his time helping to save people from natural

disasters or corrupt business men. He thought nothing

of leveling entire neighborhoods of slum dwellings

in order to force the city fathers to build decent

housing. He used his powers to terrorize munitions

makers who were, in his mind, the cause of all wars.

Except for the Ultra-Humanite and Luthor, there

didn't seem to be any supervillains for him to face

(Semich, 2003).

Coogan,

though, notes that writer "Mark Waid, who claims

to have read every single Superman story ever published,

asserts that the real shift in Superman's devotion

to social justice took place in 1945" (Coogan,

2001).

Whatever

its slope, Superman's core morality never truly

changed, even if the targets of his quest did. The

character helped to initiate the superheroic ideal

that strongly appealed to audiences at least until

the "impetus driving the Golden Age ended with

the Second World War […] with a surge in cancellation

occurring in 1949" (Coogan, 1998: 435). And

that impetus, arguably, could be the strong - almost

blind - adherence to the agreed-upon morality of

the American status quo.

By

using concepts of morality as a guide for the moment,

then Fredrick Wertham's publication of Seduction

of the Innocent becomes the most crucial event

in the post-war era for the superhero genre. Largely

because of both Wertham's popular outcry against

comic book's fallen standards and the Congressial

hearing on that matter, "the Comics Code Authority

was created, which mandated regulations that all

but sunk #1 publisher EC Comics by wiping crime

and horror comics off the shelves (some say it was

done intentionally by rival publishers to break

EC's stranglehold on the industry).

As

a result, the Code […] buried the Golden Age"

("One for the Ages", 2001: 87). However,

it also set the stage for superheroes reemergence

via an amended (and ironfistedly ordained) moral

code. Wizard says, "The comics industry

would be resurrected by trying to adapt to the Code's

rigid restrictions" (2001: 88), but that is

only half-true: the superhero genre would be resurrected,

dragging the industry along with it: "What

makes the Silver Age all the more amazing is that

it still turned the field on its ears despite working

within the rigid confines of the Comics Code. The

Code forced comics out of entertainment and more

toward morality and ethics…yet the Silver Age

embraced the restrictions and entertained nonetheless"

("One for the Ages", 2001: 94).

Once

again: by embracing the Comics Code's dictated morality

did the superhero genre survive. Thus, "DC

reinvented its classic heroes starting with Flash

in 1956's Showcase #4" ("One for the Ages",

2001: 94) paving a route to success by means of

the same Code that bound them.

Therefore,

the Golden Age begins with the implementation of

a morals-system for the superhero genre; the Silver

Age began with a forced revision of those waning

morals, namely the Comics Code. Can the Bronze Age,

with all its varied dates and events, be said to

have a precise relationship to the Code's dictated

sensibilities?

Yes,

it can and does: Amazing Spider-Man #96,

dated June 1971. Written by Stan Lee, this issue

focused on the perils of drug use. However, since

the depiction of drugs - even when portrayed negatively

- violated the Comics Code, the issue went without

the CCA's seal of approval, making it to the newsstands

and readers' hands just the same. Yes,

it can and does: Amazing Spider-Man #96,

dated June 1971. Written by Stan Lee, this issue

focused on the perils of drug use. However, since

the depiction of drugs - even when portrayed negatively

- violated the Comics Code, the issue went without

the CCA's seal of approval, making it to the newsstands

and readers' hands just the same.

In

later years, Lee would be praised for his determination:

his "courageous action was endorsed by the

U.S. Department of Health because the Spider-Man

comics attracted a large number of young readers,

a segment of the population most at risk with respect

to drug abuse" (Entertainment Industries Council,

2003). While many underground, independent creators

thrived without the CCA approval, this was the first

instance of a mainstream superhero publisher willingly

defying it in favor of a higher morality. "The

Comics Code Authority subsequently changed its rules

to support the inclusion of anti-drug abuse messages

in comics" ("One for the Ages", 2001:

91), indicating that the power to determine comic

book ethics had swayed: By the climax of the Bronze

Age, it now belonged largely to the publisher, the

main force in shaping a book's destiny and sensibilities.

"By

the mid-1980s the Comics Code, once a force powerful

enough to bring even EC's William Gaines to heel,

had become a spent force, with both Marvel and DC

insouciantly advertising many of their comics as

'Suggested for Mature Readers'" (Reynolds,

1992: 9). The Bronze Age is also marked by the onset

of "relevant comics," those that focused

on the issues then eating at America, such as trust

in government, equal rights, and foreign policy.

Many titles from this team of publishers had lead

the charge in addressing these topics, and those

books that did not were often exploring the creative

boundaries of the genre.

However,

by the 80s, that freedom had become irresponsibility.

The Code was flimsy, and there was little fear of

its violation. Marvel Comics and DC Comics - the

Big Two - operated largely as their own censors

(even though they remained part of the CCA's committee).

And, after fourteen years of determining their own

borders, the self-policing suddenly turned lazy

when Watchmen and Batman: The Dark Knight

Returns showed there was money to be made in

compromised heroes.

Certainly,

this was not Moore and Miller's intention, but it

was their effect. For at least a half-dozen years,

Marvel and DC released the reigns on hero's accountability

in favor of profit. Darkened heroes ruled the day

and "heroism itself was questioned by the psychotic

characterization of many heroes […] Heroes

seemed to serve themselves more than society"

(Coogan, 1996) It could be called an "Iron

Age" or a "Dark Age", the "Amoral

Age" or a "Tarnished Age", but perhaps

calling it a "Rust Age" for all of its

forebears serves just as well to illustrate the

point without sacrificing the metallic theme.

The

Golden Age set the moral standard, the Silver Age

revised it, the Bronze Age broke free of it, and

the Rust Age ran wild with it. The irony, it seems,

is that one of the worst offenders of this Rust

Age also serves as the most logical starting point

for the last identifiable Age.

Coogan

claims, "The Iron Age of superhero comics is

marked by numerous deaths of superheroes […]

Perhaps most emblematic of the death of the superhero

is the Iron Age's self-proclaimed greatest success,

Spawn, the corpse as superhero" (Coogan,

1996)

What

he fails to acknowledge is the fact that this emblematic

hero came not from the Big Two, but from a company

formed by "seven renegade comic artists [who]

shocked the comics establishment by walking away

from mega-giant Marvel Comics to form Image Comics

in 1992" ("One for the Ages", 2001:

92).

The

content of their books, for example their premiere

Youngblood #1 in April 1992, was largely

of the same grim-and-gritty anti-hero variety, if

not even more vacant of ethical values. But, the

formation of Image Comics echoes the same preliminary

break Marvel made with the CCA twenty years prior:

the Big Two could no longer lay sole claim on the

ethical standards found in mainstream superhero

titles. And while the founders of Image may not

have produced the creations (e.g. Spawn, Youngblood,

WildC.A.T.S., Savage Dragon) that critics might

embrace as the next generation of the superhero

genre, they did up the ante and challenge the long-undisputed

Big Two throne. The

content of their books, for example their premiere

Youngblood #1 in April 1992, was largely

of the same grim-and-gritty anti-hero variety, if

not even more vacant of ethical values. But, the

formation of Image Comics echoes the same preliminary

break Marvel made with the CCA twenty years prior:

the Big Two could no longer lay sole claim on the

ethical standards found in mainstream superhero

titles. And while the founders of Image may not

have produced the creations (e.g. Spawn, Youngblood,

WildC.A.T.S., Savage Dragon) that critics might

embrace as the next generation of the superhero

genre, they did up the ante and challenge the long-undisputed

Big Two throne.

The

precipitous rise of CrossGen, Oni Press, and even

Big Two prestige imprints like Wildstorm (which

was originally part of Image -- ed.) and Marvel

Knights owe their voices to Image; it is a stronger

Age where the spectrum of morality can be represented

- a stronger Steel Age.

In

closing, it is worth citing a favorite title amongst

the various sources used above: Busiek's own Astro

City from Homage Comics, one of the post-Image

upstart subsidiaries of Wildstorm and DC. Astro

City #1/2, "The Nearness of You",

is considered a "critically important moment"

by Klock as it recounts "the story of Michael

Tenicek, who is plagued by dreams of the same woman

every night" (2002: 88). This woman, it turns

out, was Tenicek's wife before a superhero conflict

imperfectly rewrote reality; her existence was lost

in the shuffle, and her only remaining trace exists

in Tenicek's dreams. When given the choice by the

supernatural Hanged Man to have her purged from

memory or leave that last remnant of her alone,

Tenicek chooses to remember. He finds peace from

this rational explanation and, from there, is willing

to accept the imperfections of his existence.

In

some way, perhaps this article's guide is just as

much Michael than Barbara. "While Miller's

Batman needs to create order, and Moore's Joker

finds madness in acceptance, Michael Tenicek finds

peace through understanding, not by forgetting,

but through memory" (Klock, 2002: 89). Hopefully,

that same serenity will guide further the systems

of logic in remembering the Ages.

Page

4: Chart and Citations

--

A. David Lewis

|