|

Part

1

One

For The Ages:

Barbara Gordon and the (Il)-Logic

of Comic Book Age-Dating

Part Two: The Silver Age And Beyond

So,

if June 1938 - the publication of Action Comics

#1 and the arrival of the first fully realized Superman

- marks the inception of both the Golden Age and

the superhero genre as a whole, what date captures

its next significant shift, generally called the

Silver Age?

Again,

there is broad agreement, but not quite as widespread

as Action Comics #1. A handful of individuals

point to November 1955 and the publication of Detective

Comics #225 as the inception of the Silver Age;

this issue is significant in that it first introduces

superhero J'onn J'onzz, the Martian Manhunter.

While

J'onzz is both one of the first superheroes to emerge

following the post-war slump and continues to populate

the DC Comics universe even today, his debut itself

made little impact. In their Frequently Asked Questions

(FAQ) section at Rec.Arts.Comics.DC.Universe, Jerry

Franke and Elayne Wechsler-Chaput hedge their bet

by offering both J'onzz and the more popular flashpoint

in superhero history, the emergence of the second

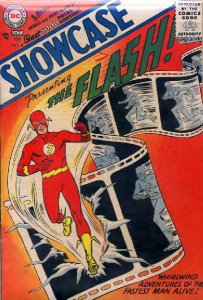

Flash, Barry Allen, in Showcase #4 published

September 1956. While

J'onzz is both one of the first superheroes to emerge

following the post-war slump and continues to populate

the DC Comics universe even today, his debut itself

made little impact. In their Frequently Asked Questions

(FAQ) section at Rec.Arts.Comics.DC.Universe, Jerry

Franke and Elayne Wechsler-Chaput hedge their bet

by offering both J'onzz and the more popular flashpoint

in superhero history, the emergence of the second

Flash, Barry Allen, in Showcase #4 published

September 1956.

In

fact, Flash's Showcase #4 ranks as the second

most expensive Silver Age book, according to Overstreet

listings, outpacing the less valuable Detective

Comics #225 ranked #9 (1999: 71).

"The

beginning of the Silver Age is Showcase #4,

the first appearance of the second Flash,"

says Busiek definitively (Lewis, 2002). And Coogan,

who overlaps the Silver Age with Schatz's Classic

stage where "conventions reach 'equilibrium'

and are mutually understood by artist and audience,"

concurs with Busiek. Dashiell also affirms Showcase

#4, saying that "the general consensus is that

the first appearance of the modernized Flash was

the beginning of the Silver Age" (1998: 80).

But,

this returns us to the conflict with the fully realized

Superman versus his earlier incarnations. Mougin

is quick to point out that, though Showcase

#4 is the first appearance of the new Flash, it

isn't until 1959 that Barry Allen inherits his own

monthly title. Of course, one has to ask, what is

significantly different from the Flash in Showcase

#4 and the Flash in Flash #105 almost three

years later? The answer: Next to nothing. The essence

of Barry Allen remains the same, making the later

headlining and later date irrelevant.

Out

of fairness, a brief summary of the potential Silver

Age conclusions seems warranted, even if ultimately

fruitless. Mougin implicates a number of suspect-dates:

Some, he says, "place it at 1970, the year

in which Jack Kirby left Marvel and started up the

Fourth World saga at DC and in which Denny O'Neill

and Neal Adams began their Green Lantern/Green Arrows.

Still others [such as Mougin himself] would date

it at 1972, the year in which Stan Lee quit writing

for Marvel and gave his editorship to Roy Thomas"

(Mougin, 1997: 72).

The

Superman Through the Ages! website, also suggests

publisher- and staff-driven alterations that trigger

both the Silver and subsequent Bronze Age. Whereas

Mort Weisinger gained "sole control over the

character" and re-enlisted Siegel "to

DC [Comics] in 1959 to write the adventures of his

creation once more," Siegel's mid-60's departure

and Weisinger's 1970 handing-of-the-baton to Julie

Schwartz signals the change of era for Semich (2003).

Franke

agrees with both Weisinger and Kirby's significance

in closing the Silver Age, and Wizard magazine

cites all of the above in addition to the three-cent

price-hike and Marvel Comics' liberating distribution

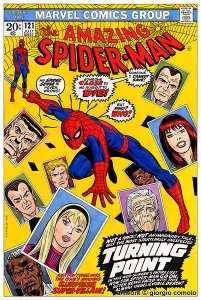

deal as all signs of the time. They also feature

Busiek's "last gasp of the Silver Age […]

the death of Gwen Stacy," Spider-Man's first

love in Amazing Spider-Man #121 circa June

1973 (Lewis, 2002). Coogan dates the Silver Age's

passing one month later with the demise of the Green

Goblin in Amazing Spider-Man #122. These

add two plot-driven dates to the heap of possibilities,

which is the point: a different criterion guides

each of these determinations. Franke

agrees with both Weisinger and Kirby's significance

in closing the Silver Age, and Wizard magazine

cites all of the above in addition to the three-cent

price-hike and Marvel Comics' liberating distribution

deal as all signs of the time. They also feature

Busiek's "last gasp of the Silver Age […]

the death of Gwen Stacy," Spider-Man's first

love in Amazing Spider-Man #121 circa June

1973 (Lewis, 2002). Coogan dates the Silver Age's

passing one month later with the demise of the Green

Goblin in Amazing Spider-Man #122. These

add two plot-driven dates to the heap of possibilities,

which is the point: a different criterion guides

each of these determinations.

The

motivations and dates are even more scrambled for

the next Age, which only some grant as Bronze. Coogan

sees this as a time of Refinement, where "formal

and stylistic details embellish the form" (2002:

430) - citing Teen Titans #32 in April 1971

as its "arbitrary" beginning (446) - whereas

Wizard calls it "the 'Age of Repackaging,'

where old ideas were spruced up for a whole new

audience" ("One for the Ages", 2001:

90).

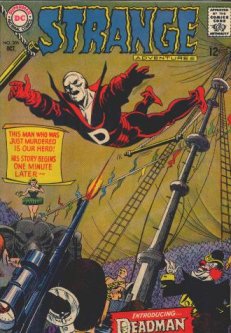

Dashiell

cites the changing climate both of the industry

and of the national as a whole; "not only was

the comic book industry experiencing a decline in

sale and personnel shake-ups, but the mood of the

country was changing as deep concerns over civil

rights, women's liberation, and the Vietnam war

were reaching critical mass" (1998: 80). For

reasons such as these, Dashiell sees the roots of

the Bronze Age taking hold back in 1967, "a

pivotal year for several reasons, not the least

of which was the debut of the landmark Deadman

series in Strange Adventures. Like Action

#1 and Showcase #4, I think Deadman represented

the birth of a concept," namely a mature, adult

audience (81).

Overstreet

might disagree with Dashiell, with Deadman having

little collector's value, certainly not enough to

crack its top 10 - but, then again, its Bronze Age

top 10 is populated by only five genuine superhero

titles, making its definition of the time rather

different from my own. Overstreet

might disagree with Dashiell, with Deadman having

little collector's value, certainly not enough to

crack its top 10 - but, then again, its Bronze Age

top 10 is populated by only five genuine superhero

titles, making its definition of the time rather

different from my own.

This

also makes Busiek's start-point of October 1970,

the first issue of Conan the Barbarian, tricky:

"The Bronze Age is starting even before Gwen

is dead […] There's a new wave of experimentation

going on with sword-and-sorcery books. And the Bronze

Age eventually gets taken over with the success

of Uncanny X-Men" (Lewis, 2002).

Busiek

may inadvertently be supporting Wizard and

Coogan's claims simultaneously: he values the creative

embellishments, but also concedes to the revamped

mutant title's dominance - in fact, Conan

#1 even says on its cover "The First Time in

Comic-Book Form!" (Thomas, 1970: cover,

my emphasis).

Bailey

shares Busiek's year, but not his reason: "To

define it in terms of specific events, we might

begin the Bronze Age with Jack Kirby's departure

from Marvel Comics around 1970" (2000). Coogan,

though, characterizes Kirby's move along with other

mass creative staff changes, the failing of Charlton

Comics, and the publications of the Overstreet Price

Guide and All In Color For a Dime as "extra-textual

events" (Coogan, 2002: 464, note 13), contributing

to, but none singularly signifying, the onset of

the Bronze Age.

All

this may make Dashiell's 1967 seem rather premature,

but other estimates are further belated. Klock suggests

that the Bronze Age, as such, never took place,

and that the Silver Age didn't reach its culmination

until 1986 with Moore's Watchmen and Frank

Miller's Batman: The Dark Knight Returns.

Klock

instead names a "Third Movement" containing

Warren Ellis' Planetary which will narratively

return "to uncover the 'Bronze Age,' the successor

to the Golden and Silver Ages of the superhero,

in their archeology of mysteries" (Klock, 2002:

167). If Klock's contention reveals anything, it

is both how individualized one's dating systems

can be and how difficult the post-Silver Ages are

to discern.

"Was

there a tombstone on the Bronze Age?" was put

to Kurt Busiek: "I think it's a little too

close to tell," he responded in a 2002 interview

(Lewis). For there to be a conclusion to the Bronze

Age, there must be a clear next Age in effect, and,

on that count, there is little agreement at all.

page

3

--

A. David Lewis

|