|

The

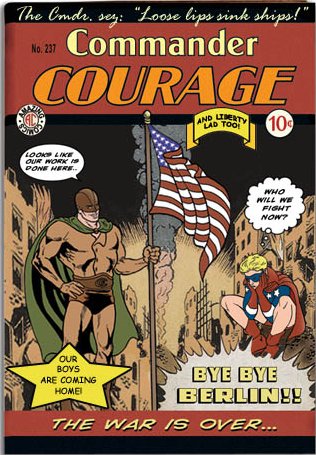

Naked Censorship of Liberty Lad

(originally published in the July,

1976 issue of Once Upon A Dime)

Though

his own courage shortened his career in comics,

Jackson Whitney had a keen grasp of what the burgeoning

superhero field would need. In the very first Commander

Courage story, "The Origin of Commander Courage,"

Whitney had fleshed out polio-stricken junior high

school teacher Jefferson Dale's supporting cast.

No mere crutches these, the staff and students of

Nathan Hale Junior High would each and every one

prove to be crucial to the mythos of Commander Courage.

None

moreso, perhaps, than Alexander "Dusty" Dale, Jefferson's

nephew and ward. Despite the already popular presence

of figures like Robin, The Boy Wonder, in Whitney's

friend Bob Kane's strip Batman, the doomed

but brave comics creator originally intended this

all-American boy to be just that: an all-American

boy. Red-blooded and true blue, Dusty Dale was something

every schoolboy could aspire to be, and I don't

just mean an Eagle Scout. None

moreso, perhaps, than Alexander "Dusty" Dale, Jefferson's

nephew and ward. Despite the already popular presence

of figures like Robin, The Boy Wonder, in Whitney's

friend Bob Kane's strip Batman, the doomed

but brave comics creator originally intended this

all-American boy to be just that: an all-American

boy. Red-blooded and true blue, Dusty Dale was something

every schoolboy could aspire to be, and I don't

just mean an Eagle Scout.

Devoid of superpowers, Dusty had heart. Ignorant

of his uncle's heroic secret identity, Dusty still

fought the good fight on the home front by example.

It's quite likely that that very example led to

the extreme scarcity of the third issue of Commander

Courage, for that featured the classic story

in which Dusty spearheaded the Nathan Hale Junior

High war paper drive. What kid could hold onto that

comic book when Dusty had made it clear that saving

comics was just playing right into Axis hands? Our

boys in Europe and the Pacific needed that paper.

When finally, nine months after the strip's creation,

Whitney finally gave in and turned the youth into

another teen sidekick in the superhero canon, it

was perhaps a bit of wish fulfillment on his part.

A justification, if you will, of the artist's desire

to fight for his country himself, not just with

the scathing power of pen and ink.

For of course, Liberty Lad would prove to be Jackson

Whitney's last creation, an act of pulp patriotism

to inspire young men everywhere just before Whitney

became a doughboy and fell lifeless somewhere in

the Forests of Ardenne.

As such, what was done to Liberty Lad by small-minded

men is nothing less than a crime, a dark moment

in the comics industry's past that sadly, few seem

to care about today.

In late 1941, comics were still seen as something

for kids, though many adults did read them. But

they had an innocence, reflective of the time and

America's willingness to still see the best in humanity

in the face of great evil. Jackson Whitney had that

innocence, too, and poured it into Liberty Lad.

By now, the origin of the fair-haired streak of

liberty has almost become the stuff of cliché. And

indeed, in later years, Julius Schwartz would borrow

heavily from Whitney's classic story to allow Wally

West to become Kid Flash, though to this day he

denies the homage.

The story refers to "the dark winter of 1942," clearly

meant to resonate with the anniversary of the day

Dusty lost his father at the treacherous attack

on Pearl Harbor. The plucky orphan visits his uncle

at the Liberty Bell museum, where he finds the older

man has recreated the very situation that gifted

him with the "Mega-will" that makes him Commander

Courage.

Meaning to provide Dusty with some inspiration,

Jefferson Dale intones the oath he had taken on

December 7, 1941, when lightning strikes twice!

The Liberty Bell tumbles from its moorings, causing

Jefferson to spill the Indian Shaman Waters he carries

with him at all times in memory of his Native American

friends. Mixing with the electrical charge of lightning

and amplified by the conducting power of the Bell,

the water splashes onto a frozen Dusty Dale, who

suddenly finds himself possessed of the quasi-mystic

Mega-will.

(Purists will note that this is not an exact

recreation of Jefferson's original transformation;

perhaps Jackson Whitney felt that the presence of

the actual Shaman Mystics a second time would have

been too coincidental. Alas, we will never know,

but it seems like a prudent choice on his part and

thus, a safe conclusion to reach. Besides, comics

creators rejiggered origins all the time, ignoring

elements they found difficult to revisit. Witness

Jack Cole's modest retooling of Lev Gleason's original

red and blue Daredevil within six months of the

character's first appearance.)

At

any rate, now armed with the same abilities as his

uncle and soon to be superhero mentor, Dusty Dale

dons the famous star spangled top and trunks of

Liberty Lad for the first time. At

any rate, now armed with the same abilities as his

uncle and soon to be superhero mentor, Dusty Dale

dons the famous star spangled top and trunks of

Liberty Lad for the first time.

Wait a minute. Trunks, I said? But we know Liberty

Lad, and he wears tightly cut breeches, not trunks,

you say.

Prepare yourselves for a shock. Up until 1953, Dusty

Dale went bare-legged, just like a few other boy

wonders. It was only the terrible but understandable

cowardice of the editor at Amazing Comics, Delmer

McNeal, that caused the change. So deep was his

shame that any comics reprinting pre-1953 stories

corrected the art to bury Liberty Lad's original

costume.

Yes, 1984 came early to comics.

The public considered comic books to be harmless

throughout World War II, even useful outlets for

juvenile imagination. But as the Cold War rolled

over the nation with its icy grip, citizens looked

to find the enemy within. And where they looked,

they found four colors for a dime.

By all accounts, McNeal was a genial if not particularly

creative man. Certainly nobody had any unusual beef

with him. If he overworked his staff, it was only

because that was the industry norm, not because

of any particular toughness on his part. He edited

comics, and as far as McNeal was concerned, comics

don't make waves.

When comics turned darker in the late forties, McNeal

was happy to follow the trend, altering even the

adventures of Commander Courage and Liberty Lad.

The misguided but still fascinating Crypt of

Courage dates from this period.

Gruesome horror and explicit violence ran red through

the pages of this so-called children's entertainment.

Some publishers tried to have their cake and eat

it, too. For instance, the classic Crime Does

Not Pay only half-heartedly sold its title message;

readers knew that the mob guys featured in its pages

lived pretty well until Johnny Law caught up with

them.

But after a couple of years of this macabre trend

(even The Marvel Family's Tawky Tawny fought and

fatally impaled a were-tiger), someone who didn't

think that comics were the cat's pajamas was bound

to notice just what was going on within their covers.

That someone, of course, was Dr. Frederic Wertham,

who linked crime and horror comics to an upswing

of juvenile delinquency and childhood psychological

disorders in his book, Seduction of the Innocent.

Read

Part Two of this classic

article, featuring the terror of Estes Kefauver!

--

Donald Swan

Advertisement

|